Gus Van Sant, Elias McConnell, and Dany Wolf

at Cannes 2003, image: festival-cannes.com

There he is, scorched in Death Valley and on the Saltflats of Utah; in a mold-closed school with a barebones crew on scooters; and on the Palais steps of Cannes, where he accepted the Palme D’Or this year for Elephant.

Gus Van Sant? Sure, he’s there, too, but I’m talking about Dany Wolf, the producer. The guy who actually has to figure out how to make the movies Gus sees in his head.

While I’ve been a fan of Van Sant’s since Drugstore Cowboy, I’ve been very interested in his recent bold filmmaking experiments, which coincide with my own entry into the field. I wanted to find out Wolf’s on-set experience and insight on making the films that are remaking film.

Below, read my November 2003 discussion with Wolf, an exclusive feature of greg.org.

[Note: No underage Filipino data entry workers were harmed in the transcription of this 3,000-word piece. Special thanks to Dany Wolf, Jay Hernandez and Jeff Hill, who aren’t doing so bad, either.]

Greg Allen: How did you first get involved in producing?

Dany Wolf: I’m originally a New Yorker [like everyone else in LA -g], and came to producing out of a commercial background. We were a little crowd in school who grew up in the commercial business. I’ve worked with a multitude of directors and crews; I did John Woo’s first commercial; did some Superbowl commercials; a Hanson music video for a song called “Weird” (read one fan’s extensive interpretation), which we shot around New York and L.A. [a range of accomplishment that impresses all but the most godless of communists. -g]

I was trained to help get what the director wants. You do what you can, and you have to be very efficient, because in the commercial business, you-re on an extremely tight deadline, and you don’t have any contingency if you go over budget; you make your living by producing well.

I first met Gus through commercials, around the time he was making To Die For, and he kept asking me to do things: sometimes it’d be a short film, sometimes a music video, sometimes a still shoot for Harper’s Bazaar. We did Allen Ginsberg’s final film appearance, a music video which got a lot of play on MTV and which went to Sundance in ’97 as a short film. Finally, with Psycho, it turned to films, and it’s been a great experience.

GA: That’s interesting. Usually, the default is to consider just a director’s feature films, not all the things they’re working on in the interim.

DW: Any director or creative’s career, you look at it and evaluate from the outside, there are these hills and valleys, but that’s a matter of perspective. From the inside, working on the past four films with Gus, it has been a wonderful, positive experience. People talk about how he was doing the studio stuff and now he’s back to his roots, but from my perspective, being right next to him, he’s remained very true to his instincts throughout.

He’s not strategic about, oh I want to make an art film, or, I want to make a studio melodrama. Now he is enjoying the creative freedom of making smaller films and not being constrained by the normal ways of making films. He’s been breaking the mold in a lot of ways by not working with traditional scripts or trained actors, for example. He is not only a very talented artist, but he creates an environment that is nurturing for actors and crew. The day-to-day of this kind of filmmaking is very rewarding.

[DW: continues extensive and unabashed praise of Gus Van Sant. And I mean extensive.

GA: responds with gushing expressions of awe and teenager-like admiration of Gus Van Sant. Repeats. Repeats. Wonders if Jules Asner’s spot on E! is available. Dispels any of Asner’s job insecurity by asking about film with disappointing box office.]

GA: How was it working on Psycho?

DW: It was like doing a doctoral thesis on Hitchcock, in a sense. We brought in his AD and script supervisor as technical consultants. And we had access to his daughter, Pat Hitchcock. Gus saw it as an experiment, both of filmmaking and of marketing. It was audacious to treat film like theater, and he was vilified for it. Just the announcement got people worked up: how could you tread on such hallowed ground? But we heard from Pat that he would’ve gotten it.

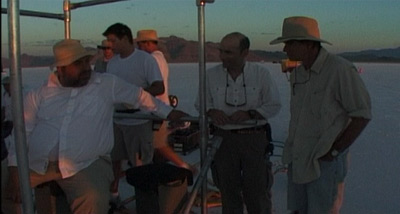

Wolf, Van Sant, and Casey Affleck on the set of Gerry, image: F. Andrew, Salt Lake Van Sant

GA: What was pre-production and shooting like for Gerry? Watching Salt Lake Van Sant on the DVD, it looked pretty calm, especially considering you’re trying to time this massive dolly shot to the sunrise.

DW: That’s just because I wasn’t in it very much. Gerry‘s an extreme case. We started in Argentina, and because of weather, we changed locations and ended up in Death Valley in July. We had three people drop from heat exhaustion on the first day; we were doing IV’s to recover their fluid levels. but by the end, which you see in Salt Lake Van Sant, it’s kind of euphoric, we’re finally seeing daylight. [pun, intended or not, I don-t know. -g]

GA: Oh, right. I remember now. You were shooting in sequence.

DW: [You read the voluminous published interviews with Gus well, grasshopper. But don’t interrupt.] Right. For that shot, first, we had Jim Kwiatkowski, an amazing grip who also does Spielberg’s films. That’s a 500-yard dolly shot. Spielberg’d heard about it before the movie came out. People were definitely talking about it, and everyone always asking how we did it. That’s why we put it on the DVD. I think Felix [Andrew, who, in addition to shooting the making-of doc, also mixed the sound] caught the mood pretty well.

IMDb Links

Dany Wolf

Gus Van Sant

Harris Savides

Jim Kwiatkowski

Elephant

Gerry

PsychoFor a lot of the other shots, we had this little thing– Gus, Matt, and Casey were writing the script and then they’d throw it away; it was very kinetic. [note to self: avoid using ‘kinetic’ in studio pitches. -g.] I’ve said this before: with Gerry and Elephant, we’re seeing a very pure, unfiltered creative expression, it’s very hard to do in film, with studios, producers, etc. [note to self: consider avoiding studio pitches altogether. -g.]

[Is it really so bad that you’d go to the middle of Death Valley in order to not have studio suits poking around your set? Or that you’d work without a script rather than stare down development execs with their reams of notes? The mind reels. -g.]

GA: What did your shooting day look like? How many setups would you get each day, for example?

DW: We had a little thing that Gus and I would do in advance, where we’d map out the type of locations and build each day off of that. It became very geographic. Then I’d kind of lay it out with Jim. While we were shooting one landscape in the morning, for example, Jim and his crew would be setting up for a completely different-looking shot nearby.

We would take siestas during the hottest hours of the day, which is very hard to do with a union crew, but it was just another sign of their amazing commitment to the experiment. We’d work from 4 to 11 AM, then sleep, and start again working from 5-9. What happens, then, is you’re getting the magic hour, during the longest days of the year, for the whole film. It was amazing. I can’t say enough about Jim Kwiatkowski; here he’d just come off Minority Report and AI, and he comes to work for spit in the desert like that. Our Steadicam was Matias Mesa.

[I just found a great interview with GVS and Ed Gonzalez at Slant Magazine that dovetails very well with Dany’s account. Check it out. Thanks, GreenCine.]

GA: How did you make sure you were getting what you needed in that environment, or is that not the right description of the process, not driven by coverage, per se? Gus told Scott Macauley in Filmmaker Magazine that he’d cut dailies together with iMovie?? Is that all you had?

DW: Well, he would try out things together with our video taps. Because of Argentina, we had time to look at what we’d done for the first week of shooting, so we figured it’d work. That’s the risk though. And remember, we didn’t have taps on everything. But there’s a fair amount of Steadicam, and you know you’re getting good negative reports, so you have those takes.

Harris Savides, Wolf, and Van Sant on the set of Gerry, image: F. Andrew, SaltLake Van Sant

The main thing, though, is that Gus didn’t second guess himself, wondering, maybe I need to cover this. That’s what you’re seeing with these long master shots and not a lot of editing. It’s a relentless going forward, without getting takes ad nauseum.

GA: Your credits in both Gerry and Elephant are Producer and AD, which sounds crazy. Is that an unusual combination? Does it just mean you’re the guy who gets no sleep, ever? Is it a function of the way the movie was shot?

DW: And UPM (unit production manager). It meant really bad script notes. [one of the AD’s main jobs when there’s no assistant editor. That’s what the iMovie’s for, I guess. -g.] Part of it was Gus’s push to get smaller and smaller and smaller, back to the intimacy of Mala Noche. I wasn’t there, but Gus’d tell these stories of five guys sitting around a table asking, does anybody know somebody? And you’d find someone’s friend who works in a restaurant, and you call him up, and check it out, and later that night, you’re shooting.

But I was used to it. In commercials, when you went overseas, you’d sometimes find out you’re better than whoever they gave you as AD. You’ve just gotta get it done, so you jump in and do whatever it takes. That’s sort of how it came about.

GA: The number of credits per person, it’s almost like Robert Rodriguez’s production style, where he does everything.

DW: Yeah, there is a bit of that Rebel Without A Crew philosophy. Gus is very interested all along the way. He’s very involved in the sound; he’s on the mixing board when we’re finaling; he does the music. But for certain movies you just don’t need the army. You’re adding time, putting things between you and your actors. Now, so many people just plug their numbers into their Moviemagic budget, their productions are very similar.

Believe me, Gus pushes me hard to not just automatically do everything the accepted way. It’s a challenge to the mindset that there’s one right way to do things. His questioning instills an awareness that’s useful when you do need to follow a traditional routine, too.

GA: Were there similarities or learnings from Gerry that helped you on Elephant?

DW: There wouldn’t be an Elephant without a Gerry. It informed Gus and gave him the confidence in his approach. He learned from that experience how liberating it could be.

GA: What did the writing and pre-production processes look like for Elephant?

DW: Early on, Gus had said he liked what JT (Leroy) [who sounds like the love child of the River and Keanu characters in My Own Private Idaho. -g.] wrote. That got it started. With Elephant, we did a fair amount of casting and scouting. By casting and working with the kids- putting them in different groups, picking different people for each callback, then just getting them to divulge more than they know – Gus was able to go off and write a sceneplay. [where broad descriptions of what happens in a scene stand in for specific dialogue. With Psycho, Van Sant hewed precisely to the original script and editing, precisely the conventions he eliminated in Gerry and especially Elephant. His approach may be experimental, but it’s a rather well-controlled experiment. -g].

GA: How far into pre-production was that? Were you involved at that point?

DW: Once it was proposed we shoot in Seattle, that’s when I got more involved. Then we switched it to Oregon, and I just ramped up a huge open casting, found the school, and within a month or two we were in production. We were working Wednesday through Sunday, and it was tricky because we were working with kids, which had time restrictions. Plus, if you rehearse too much they change from natural kids being themselves. You really had to be sensitive to the environment you’re creating.

GA: When we saw that school–which I think is awesome-looking in an ominous Wallpaper-magazine kind of way–we decided we could never send our kids to public school. How did you find it?

DW: Oh, yeah, it was beyond creepy. That school was shut down, it had mold and different issues, and we had to deal with environmental stuff to make it safe to work there. It was amazing for a crew, though. The grips had the wood shop, the camera crew used the darkroom. Everybody had an office; the PA’s had the vice principal’s office. And we all drove around on these little Razor scooters.

Amazon Links

Gerry

Psycho

Finding Forrester

Rebel Without a Crew, Robert Rodriguez’s production journal for El MariachiI love having production and everybody together, everybody eating together, the tighter you are the better the communication. I mean, I’m a New York producer, and I’ve gone in and out of lofts, too, with the holding area five blocks away, but having everyone together created a great atmosphere.

GA: If someone wants to shoot low-impact, Elephant-style, are there different things to consider when picking a location?

DW: To find one that works for everyone. Consult with everyone involved in advance. You have to prep really intelligently, be prepared for saying oh well, we’re not doing this now. Then you can have the spontaneity to say, we’re gonna do this because the light’s perfect.

But Gus is experienced, and he knows Harris (Savides, the DP) can make a movie with five candles, if he has to. And no lighter. He understands the scale of things, and can adapt, and he never says, I need the eight guys to light this shot. It takes real expertise to change what you think you’ve gotta have.

GA: The video game Eric and Alex play has the characters from Gerry wandering around a desert.

DW: Wow, that’s really good you picked that up. Not many people notice that.

GA: [Actually, I didn’t notice it, either; my wife did.] Thanks. I’ve written a couple of things about the connection between Gerry and video games, so… [Tell him your wife spotted it. Tell him your wife spotted it!]

It creates a clear connection between the two films. Are there any other references buried in there? [You’re gonna get busted when she reads this, dude. So busted.]

DW: No, I think that’s the only one.

GA: How did it get in there?

DW: We wanted to have a video game like Grand Theft Auto, but there was no way a video game maker’s going to license their title for the film.

GA: Why not?

DW: [Have you seen the movie or read a newspaper?] Because of the subject matter, really.

GA: Oh, right. [It’s a school shooting movie, idiot. Pay attention.]

DW: So we hired a game designer, gave him the images from Gerry, and he programmed it for us.

GA: Yeah, Quake and Doom and other games let you customize your own levels and create your own characters. There’s this whole movement now where people are using these video game engines to create films. They program it all up, create the sets and characters in the game, block out their scenes, then one player is the camera, and he records the action. Then they do voiceover. It’s called machinima. Do you know it?

DW: First I’ve heard of it.

GA: There’s this one series called Red vs. Blue, which these guys make using four X-Boxes. It’s hilarious. You should check it out.

DW: Sounds cool.

GA: I’ll send you the link.

DW: Gus has talked about the influence of games like Tomb Raider on Gerry. You go nuts watching these video games, how do I do this with a camera? [Go nuts? Video games make you want to go out and shoot something?? Ix-nay on the ideo-vay ames-gay, any-Day. -g. [Heh. any-Day. That-s cool.-g.]]

GA: I’ve had this idea, after seeing Gerry, of doing a shot-for-shot remake of it, but set it in Los Angeles. These two Westside guys get lost in East LA or Baldwin Park or wherever, and they can’t communicate with anyone. Their dialogue stays exactly the same, and in the mean time, all these amazing stories are going on around them in other languages. It becomes this whole parable of their own alienation, disconnection.

DW: [What the hell? Is this guy interviewing me or pitching me? Do I need to pretend I have another call now? Aren’t there screeners in place for this? Waitaminnit, this idea sounds crazy, but it just might work. Get me Gus Van Sant on the horn.]

GA: You’d shoot it in DV, with a run-and-gun crew, so it’d be completely different, but the same. But as I’m thinking about how you’d actually shoot it, you’d need to choreograph and time the action behind the actors and the camera movement so carefully. It’s an incredible challenge. It’s more like Russian Ark or Elephant, really, than just Gerry, which is so pared down.

DW: [I’d better clear my calendar to get Gerry 2 into development. What? Elephant? Ahh, maybe this is just a question intended to impress me with his filmmaking acumen.] That’s true. On Elephant, it was very difficult to do that kind of choreography. Because of camera ramping, sound layers, background action, there can be 12-15 physical cues in a shot, and if you miss one, the shot’s trashed.

GA: How does a producer’s role differ on features vs. documentaries like The Agronomist?

DW: [pause] The what?

GA: The Agronomist, Jonathan Demme’s documentary. I had one question in particular, because it’s listed on IMDb as completed in 2003, but Demme talked about it at this year’s Full Frame Documentary Festival as a work in progress.

DW: I didn’t work on The Agronomist.

GA: –Because it’s listed on IMDb as your latest project–It’s Demme�s labor of love; he’s been gathering footage for ten years on this radio journalist in Haiti–

DW: Nope. I’m not involved. Maybe it’s an invitation that he wants me on the project.

GA: Yeah, call Demme. I’ll give him a heads up that you’re interested.

DW: So it says this on my IMDb.com profile? What else is on there?

GA: You’ve never checked?

DW: Nope.

GA: I just figured everyone in LA’s always checking themselves on IMDb and HSX, seeing how they’re doing.

DW: I guess I’d better check mine and update it. [he did, today. The Agronomist gone, along with much of the humorous wrapup for my interview. -g.] What else is on there?

GA: There’s The Secret World of Professional Wrestling. Did you do that?

DW: Nope. [laughs] Really?

GA: There goes my whole page of questions about Gus’s role in the and the exploration of the male aesthetic in your work.

DW: [laughing] What else you got?

GA: That’s about it, then. Thanks a lot. It’s been really great talking with you. You should fix that IMDb profile.

DW: I will. It’s been a pleasure talking with you, too. Now when did you say this is running in the Times?

[sudden sweating. phone line goes dead.]

DW: Hello? Elvis, are you still there? Hello?