I’ve been listening to WNYC’s anniversary tribute programming for John Cage, and it’s really great [if a bit over-narrated; I mean, who’s going to listen to 24h33m of John Cage programming on-demand who isn’t at least somewhat familiar with his work already?]

One 1944 composition, Chess Pieces, was only rediscovered and played for the first time in 2005.

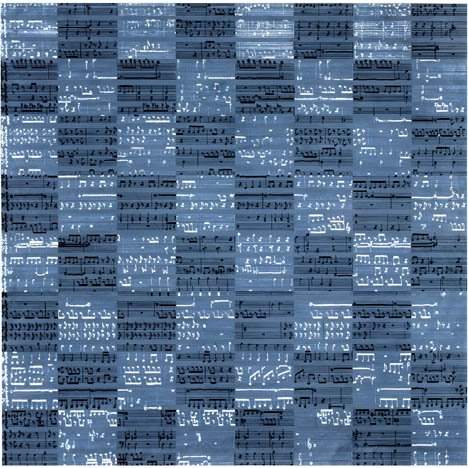

Cage had been invited to participate in a chess-themed exhibit at the Julian Levy Gallery organized by Max Ernst and Marcel Duchamp, and he created a chessboard-sized painting with fragments of musical scores in each of the squares. Each square held about twelve measures in three rows. The painting went into a private collection where it remains, almost completely invisible to the outside Cageian world until 2005, when the Noguchi Museum recreated the 1944 exhibit, “The Imagery of Chess.” [Noguchi had contributed a chess set to the show, as did artists such as Man Ray and Alexander Calder.]

Anyway, Cage pianist Margaret Leng Tan was commissioned to transcribe and perform the score in the painting, which premiered alongside the 2005 exhibit. The DVD of the Chess Pieces performance includes several other Cage sonatas and some short-sounding documentaries, including one about the history of the work. Not sure what that means.

As a painting, the collaged, juxtaposed chaos of the notes contrasts with the order of the grid. It kind of reminds me of the cut-up technique William Burroughs and the Beats’ applied to books and printed texts a few years later. [The history of cut-up mentions an interesting, even earlier reference: Dada pioneer Tristan Tzara, who was expelled from Breton’s Surrealist movement when he tried to create poetry by pulling words out of a hat.]

As a musical composition, Chess Pieces is nice, old-school Cage, abstract and occasionally abrupt, but with a still-traditional piano feel. Since the piece’s randomness comes from its structure–the distribution of the notational fragments across the grid–and not from the performer’s own decisions, it somehow has a “composed” feeling to it. So though it’s new to audiences today, it’s also classic, early Cage.