Reading through the press release for the new upscale family travel site Poshbrood.com, I was surprised and promptly filled with dread by the chance to win a “faboo Mark Cross saddlebag.”

Because that means someone has brought the luxury brand back from the dead because, what, zombies are really on trend right now? Because if you have any concept of venerable or luxury or heritage or leather or gift or anything when you hear the name Mark Cross, it has literally nothing to do with anything actually happening or made this millennium. And that residual brand goodwill embedded in your brain is now the intellectual property of a roving band of scavenging garmentos and opportunistic luggage salesmen.

Which, God bless’em, credit where it’s due, but also blame, awful, tacky blame.

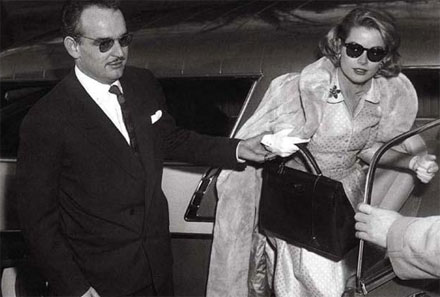

To read the contemporary press, Mark Cross sounds like a typical heritage brand revival play, immediately pressing into service its best celebrity product placement to date, a namecheck in Hitchcock’s 1954 Rear Window. From StyleList’s breathless “sneak peek” of the “exclusive” relaunch last fall at Saks:

iconic beauty Grace Kelly ravishingly shows Jimmy Stewart what can fit into a Mark Cross overnight case. The case epitomizes the brand’s look: understated and sophisticated, yet still practical.

After some tumultuous years, the company closed in 1997. But it found a champion in new CEO and president Neal J. Fox.

Fox admired the brand for its workmanship and timeless style. “It was America’s Hermès, America’s Gucci,” he asserts. Elizabeth Taylor once snapped up 70 pieces of matched Mark Cross luggage for herself and Richard Burton. [And, according to an earlier time Cross flacked that story, for their maid.]

“I really became enamored of the brand,” Fox recalls. After it shut down, he and a partner scooped up the trademark. The bags are now produced in the Pacific Rim, using French and Italian leathers.

I love it. Tumultuous. Workmanship, America’s Hermes. Scooped up, Pacific Rim. Oh wait, here are two more words I love: patchy and anonymous. As in:

Since the Mark Cross archive was patchy, Fox’s design team balanced past innovations and current styles. “It forced us to stretch our imagination, to update history in the proper way,” explains one designer. (Fox keeps his team anonymous for now.)

Before we stretch our imagination of history too far, let’s not, for once, ignore the present. For example, this article from Women’s Wear Daily in late 2008, “Mark Cross Returns With QVC Exclusive”. QVC!

WWD mentions Mr. Fox, whose wife, Martha Kramer, “will be [was?] on the channel selling the products. ‘We want to establish traction with the brand first on QVC [!] and reintroduce the brand to the broader marketplace.’ [Fox said.]” The article also pushes the clock back a little bit on that trademark scooping, too:

Six years ago, Mark Cross was purchased by private investors, including J.P. Wilkin Jr., from Sara Lee Corp., which let the brand languish do to its focus on Coach.

Ah, no it was not, and no they did not.

After a half-assed attempt to sell in mid-1997, Coach killed Mark Cross and dumped the body. Wilkin, who claims his effort to buy the company was cut short by Sara Lee, watched and waited a few years, and then pounced on the trademarks. And won.

Let’s back up a bit to see if we can figure out why a cake company was owning a luxury retailer and leather goods emporium in the first place. Partly because in the 1980s, Sara Lee was already a huge apparel company, with Hanes, L’eggs, and Isotoner gloves. In 1985, they bought Coach, a $20 million/yr, bag manufacturer, from Miles and Lillian Cahn. Who promptly retired upstate to make goat cheese while their 34th St factory was turned into a showroom for a vastly expanded product line, which was made overseas.

They bought Mark Cross, then a 23-store chain, in 1993 for $7.5 million from the faltering Rhode Island penmaker A.T. Cross [no relation], with the plan of making it Coach’s premium line. But just four years later, they put the 152-year-old company up for sale, then unceremoniously withdrew it, closed everything down, and shuttered the remaining stores. And because consumers are stupid and have no memory and it obviously doesn’t matter anyway, the relentlessly middlebrow Coach went on to become a $2.5 billion company, which launched its own premium collection in 2007 called, unironically, Legacy.

They bought Mark Cross, then a 23-store chain, in 1993 for $7.5 million from the faltering Rhode Island penmaker A.T. Cross [no relation], with the plan of making it Coach’s premium line. But just four years later, they put the 152-year-old company up for sale, then unceremoniously withdrew it, closed everything down, and shuttered the remaining stores. And because consumers are stupid and have no memory and it obviously doesn’t matter anyway, the relentlessly middlebrow Coach went on to become a $2.5 billion company, which launched its own premium collection in 2007 called, unironically, Legacy.

“MARK CROSS IS A FANCIFUL NAME DERIVED FROM MARK W. CROSS, DECEASED.”

That’s the note on one of the two earliest trademarks, filed in 1949, by the Mark Cross Company for their lion head logo. There are 38 different Mark Cross-related trademarks in the USPTO’s database. Although the company’s founding was officially 1845, the earliest use cited is from 1897. Mark W. Cross was the founder Henry Cross’s son.

image: 1914 Mark Cross ad from Vanity Fair, via bagladyemporium’s collection]

At the turn of the last century, the Crosses sold the company to an employee, Patrick Murphy, by which time they had established stores, including one on lower Fifth Avenue selling saddles, bags, gifts and leathergoods from suppliers in the US and the UK. The store introduced the wristwatch to the US. Murphy’s son and daughter-in-law, Gerald and Sara Murphy, introduced summering to the French Riviera. Fitzgerald patterned some of his characters after them. The 1930s relocation of the Cross store to Robert Goelet’s new building on 37th St, near Lord & Taylor & B. Altman, marked the dawn of a new, farther uptown era of Fifth Avenue retail. But in 1947, the Murphys sold out–or “merged with”–Drake America, a British-owned export holding company and merchant bank. That’s when the trademarking really started. And the celebrity endorsements.

[Though her Cross promotion didn’t have nearly the impact of her next role. In 1956, as the pregnant Princess Grace was photographed holding an Hermes purse over her belly; the sac à dépêches, a 1935 design, became rapidly and permanently known as the Kelly Bag.]

In 1962, George Wasserberger and three other young entrepreneurs bought Cross from Drake, and set out to expand the retail network for traditional luxury gifts. By the time he sold the company to A.T. Cross in late 1983 for $5.5 million, there were 18 locations and a catalogue business.

But in 1988, the Times described Cross under Cross as both “having an identity crisis” and as “British and stodgy.” The pen business tanked, and maketing consultant Maria Manfretti was brought in to mine Mark Cross’s design archives for

classics… like hatboxes, camera cases, duffel bags and rigid-frame handbags…

“Mark Cross hasn’t kept up with the contemporization of the market,” [she said.] ”My big dream is to take this name that had a glorious past and give it a glorious future

Yes, well. Enter Sara Lee in 1993, the sixth owners of the 23-store chain, and exit Sara Lee in 1998, when they shut down the last seven stores.

And then enter Florida luggage salesman J.P. Wilkin Jr. in 2001. He assiduously watched for the requisite three years of commercial inactivity that constitutes abandonment of a trademark, then he registered the trademarks himself for the Mark W. Cross Company, and he filed a petition seeking to cancel any claims Sara Lee and Coach [which spun off in an IPO in 2000] had on the Mark Cross IP. And he won.

That 2001 South Florida Business Journal article reports Wilkins had unnamed partners. And Fox, a longtime retail industry executive who has spent the 2000’s investing a complicated array of brand licensing companies that all involve Girbaud, was first attached to Mark W. Cross as early as 2003.

There’s no reporting online, but the USPTO database shows a couple of dead trademarks registered in 2005-6 by Avenue Brands, a premium zombie brand subsidiary created by the consumer products brand investment firm River West Brands to handle the acquisition of the Bonwit Teller IP. Maybe there was a Mark Cross deal in play there for a moment, who knows. TheDeal.com had a good overview article in brand trading and zombie/revival brands in 2005 that cites Wilkin’s Mark Cross coup as a bold/sobering tale for IP holders.

But while it would explain the current, uh, patchiness of the Cross archive, this less than pristine provenance apparently did not fit the fanciful, emotional story Fox and Wilkin wanted to recapture for their made-in-China, home shopping network premium value zombie brand. Go figure.

Yes, as you could probably guess, and as if it mattered, the “new” Mark Cross bags suck, particularly in comparison to the old ones, or more accurately, in comparison to the residual image of the old brand as it lingers in middle-aged women’s memories.

It’s good they waited with their many exclusive launches, because Mark Cross’s brand bait & switch is exactly the kind of hypothetical residual trademark goodwill fraud that IP lawyer Jerome Gilson was warning about in his harsh, embattled, yet ultimately toothless 2008 rainmaking white paper, “Zombie Trademarks: A Windfall and a Pitfall.” [Unlike Gilson, btw, I say zombie brand out of love.]

And anyway. This Mark Cross, this is the company that is supposed to be the “American Hermes”? Hermes, which has been run by the same family since its founding? Hermes which has had a remarkable streak of iconic, culture-shifting products, from the bags to the scarves to the ties to the other bags, to those weird enamel bangle bracelets everyone in Japan wants? Hermes which bought its various suppliers over the years, becoming its own organic luxury goods conglomerate? Mark Cross which may have had some eight-figure revenue years in the 1960s, emphasis on the may?

In the interest of heritage, authenticity, legacy, and timeless style, let me offer the most recent owners of the Mark Cross trademark regime five true stories from the Times archive, which I found while researching the actual, as opposed to the mythologized, history of the company.

I think they capture the enduring, discrete allure of the Mark Cross brand and are terribly on trend right now. Because I’m cheap, I will only summarize the four behind the paywall. Mark Cross was held up at least twice in the 1920s; one armed robbery in the store, and one jumping of the employee bringing the payroll. In both cases, the incidents were not publicized until well afterward, so as not to upset the clientele.

And there were at least three stories about what we can call the brand’s aspirational appeal. Here’s the best one:

In 1917, the Times reported the awesome tale of one Carl G. Frossel, a Chicago immigrant who went around town for nearly two weeks posing as “A. F. Ekengren, Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to the United States from Sweden,” and bouncing elaborately decorated checks.

After his eventual arrest in a merchandise-filled suite at the Waldorf Hotel, Frossel “told the detectives that he had the ornate check book made in New York. He had a large number of engraved cards bearing the inscription, ‘Wilhelm A.F. Ekengren, Minister from Sweden.'”

At the Ritz Carlton, they’d hung the Swedish flag in his honor. At the Plaza, he almost ran into the actual Minister Ekengren, who showed up for actual diplomatic business. And at “many high-class shops” in town, he was greeted with flourish–and then pursued.

Among the possessions of the “Minister” the detectives found a watch, which the man had bought at Tiffany’s with a check; several leather bags from Cross’s, and a number of checks already made out for other purchases.