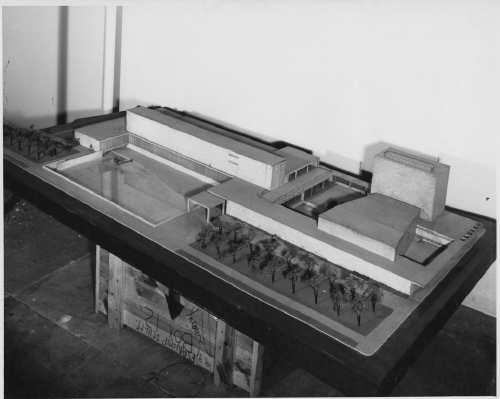

Huh, so I’m poking around online for info on the Saarinens’ unrealized design for a Smithsonian Gallery of Art [above is a SI photo of the model, built in 1939 by Ray and Charles Eames, of all people, perched atop, of all things, the crate for a Paul Manship sculpture. And I’m thinking how it’s too bad that WWII happened, because otherwise we’d have a sweet modernist art museum on the Mall–hah, as if.]

[According to the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s own history, the building never had a chance. It wasn’t Congressional budget cuts or wartime reprioritizations that killed the project–it was the rejection of the modernist design by the Smithsonian Regents themselves, and by the Commission on Fine Arts–because it was modernist.]

[Charles Moore, an influential retired Chairman of the CFA called its “sheer ugliness…an epitome of the chaos of the Nazi art of today.” Which, yow. The Commission which rejected it included sculptors Paul Manship and Mahonri Young, a grandson of Brigham Young.]

But that’s not the point. Point is, a quote stuck out from the book as being both timely and relevant. It’s from Holger Cahill, head of the WPA’s Federal Art Project [and holy smokes, Mr. Dorothy Miller], which organized artists to make work for public buildings and spaces. He believed art and artists and the public all benefit by “a sense of an active participation in the life and thought and movement of their own time.”

I haven’t found the original publication info, but since the source of that 1936 quote only appears on Google as a writing sample for an English 201 course, I put the whole thing after the jump. Take a read and try to imagine it as not a politicized, partisanized view of contemporary art:

A full and free expression on the part of creative artists may have come about in a measure at this time because of a release from the grueling pressure which most of them suffered during the early part of the Depression. It seems to have its origin also in a special set of circumstances determined by the Federal Art Project. The new and outstanding situation is that these artists have been working with a growing sense of public demand for what they produce. For the first time in American art history a direct and sound relationship has been established between the American public and the artist. Community organizations of all kinds have asked for his work. In the discussions and interchanges between the artist and the public concerning murals, easel paintings, prints, and sculptures for public buildings, through the arrangements for allocations of art in many forms to schools and libraries, an active and often very human relationship has been created. The artist has become aware of every type of community demand for art, and has had the prospect of increasingly larger audiences, of greatly extended public interest. There has been at least the promise of a broader and socially sounder base for American art with the suggestion that the age-old cleavage between artist and public is not dictated by the very nature of our society. New horizons have come into view.

American artists have discovered that they have work to do in the world. Awareness of society’s need and desire for what they can produce has given them a new sense of continuity and assurance. This awareness has served to enhance the already apparent trend toward social content in art. In some instances the search for social content has taken the form of an illustrative approach to certain aspects of the contemporary American scene–a swing back to the point of view of the genre painters of the nineteenth century. Evidences of social satire have also appeared. In many phases of American expression this has been no more than a reaction against the genteel tradition or a confession of helplessness. The dominant trend today, as illustrated by the project work, is more positive. There is a development toward greater vigor, unity, and clarity of statement….

The idea which has seemed most fruitful in contemporary art–particularly as shown by the work of artists under the Project–has been that of participation. Though the measure of security provided by the government in these difficult times unquestionably has been important, a sense of an active participation in the life and thought and movement of their own time has undoubtedly been even more significant for a large number of artists, particularly those in the younger groups. A new concept of social loyalty and responsibility, of the artist’s union with his fellow men in origin and in destiny, seems to be replacing the romantic concept of nature which for so many years gave to artists and to many others a unifying approach to art. This concept is capable of great development in intellectual range and emotional power. This is what gives meaning to the social content of art in its deepest sense. An end seems to be in sight to the kind of detachment which removed the artist from common experience, and which at its worst gave rise to an art merely for the museum, or a rarefied preciousness. This change does not mean any loss in the peculiarly personal expression which any artist of marked gifts will necessarily develop; rather it means a greater scope and freedom for a more complete personal expression.