So in my ersatz zigzagging through the history of photomurals, I kind of skipped from Edward Steichen’s landmark Family of Man exhibition in 1955, where Paul Rudolph deployed enlarged photo prints for content and experience, as well as architectural elements in his exhibition design; to Capt. Steichen’s 1945 exhibition Power in the Pacific, which featured the work of the US Navy photography unit he commanded; to Steichen’s participation in MoMA’s first photography exhibition ever, a 1932 photomural invitational, which was intended to serve as a showroom for American artists, who faced stiff mural competition during the Depression from south of the border.

Sensing a trend here? Wondering what I missed? Wow. Michael from Stopping Off Place just forwarded me the link to MoMA’s bulletin for Road To Victory, a stunning 1942 photo exhibition that rolls up so many greg.org interests, it is kind of freaking me out right now. And the man who is bringing it to me? Lt. Comm. Edward Steichen.

I mean, I kind of stumbled onto the photomural trail last October, when a vintage exhibition print of Mies’ Barcelona Pavilion came up at auction. Its size, scale, and iconic modernist subject suddenly made the photomural seem like a missing link in the contemporary development of both photography and painting. And yet it’s also seeming like not many of these pictures survived, because they were merely exhibition collateral, functional propaganda material, no more an artwork than the brochure or the press release.

And yet these things existed. Is it possible at all that any of these prints still exist in some art handler’s garage?

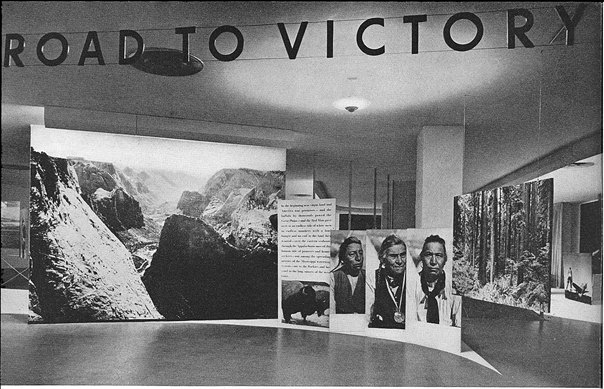

Anyway, it’ll take me time to process this Road To Victory show, so I’m just going to skip across the most stunning parts: the show’s awesome, explicit propagandistic objectives; the utterly fresh painterly abstraction of these giant prints; the spatial, experiential design of Herber Bayer’s installation; the texts surrounding the exhibit, which traveled around the country in 1942 to apparently wild, patriotic acclaim; and the ironic, complicating aspects of authorship of the show and the work in it.

[Hint: they barely identify, much less mention the actual photographers at all. I, meanwhile, am happy and grateful to credit PhotoEphemera for these small versions of much larger scans of MoMA’s 1942 documentation of the show. Definitely worth diving into.]

From what I can find so far, the key documents of Road To Victory are:

The MoMA Bulletin about the show, from June 1942, which is interestingly titled, “Road To Victory: A Procession of Photographs of The Nation At War.” The show is “Directed by Lt. Comm. Edward Steichen, USNR, Text by Carl Sandburg.” A Procession of Photographs.

The Museum’s media call, dated May 13, 1943 [pdf], which invites reporters to attend a press conference with the “Two Famous Americans” to talk about their show. Some highlights:

It is by no means a photography exhibition in the ordinary sense but one of the most powerful propaganda efforts yet attempted.

…

There will be no photographs available, but photographers will be welcome and may take pictures of Steichen and Sandburg directing the initial installation of the exhibition, which has great pictorial possibilities as a photographic background for the two. [emphasis added for awesome proto-Sforzian backdrop reference.]

In the press release proper on the 13th, the Museum emphasizes the power and significance of the show:

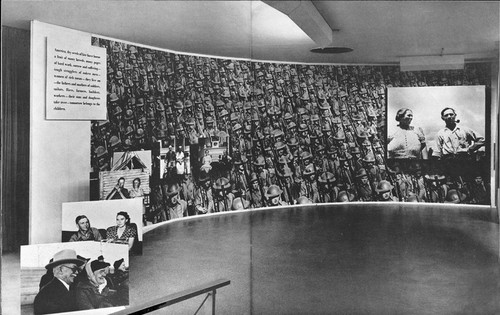

For the huge exhibition Road To Victory: A Procession of Photographs of the Nation at War, which opens to the public May 21, the Museum of Modern Art has knocked down all the interior walls of its second floor and will leave most of the space open for a spectacular installation which will show the United States at war. Not only its fighting men but the country’s resources and its people–farmers, workers, housewives, mothers, fathers, children–will be shown in mural-size enlargements, one of which measures 10 feet x 40 feet, and most of which are not less than 3 feet x 4 feet.

Here’s that giant photo, by the way, and yes, it is classic, military-style Sforzian wallpaper. I’m sure this is where the news guys wanted Steichen and Sandburg to stand.

There’s a quote from the Museum’s Director of Exhibitions Monroe Wheeler, explaining the purpose for the show:

Our purpose in preparing this exhibition was to enable every American to see himself as a vital and indispensable element of victory. Throughout the giant procession of photographs of our farms and industries and our armed forces in actual combat there recur, again and again, the faces of the fathers and mothers and sons and daughters upon whom everything else depends.

The gravity of our struggle has not been minimized, but I think no one can see the exhibition without feeling that he is a part of the power that is America.

There’s a part of Steichen’s lengthy, eclectic biography that jumped out at me. It’s not the final paragraph about his delphiniums, but the part about going from being “the chief stimulus in this country for the modern trend in the arts” to becoming the chief of the photographic division of the American Air Corps in France in WWI

The necessity of clarity and detail in aerial work gave him a new concept of photography, and in 1920 he gave up painting to devote his time to photography.

Now that Google has made aerial photography a primary interface for engaging the world, I think I need to look into this “new concept of photography” angle.

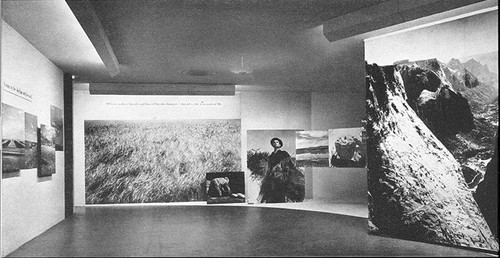

The press release for the actual exhibition [pdf] is really a narrated walkthrough, a script, with all of Sandburg’s wall texts punctuated by brief descriptions of each photo. My favorite line of the whole, overheated thing has to be “Grain to the skyline and beyond,” the supertitle for this incredible photo that feels like it would feel like a Twombly.

But who’s it by? Hard to say. The press materials not only don’t mention any photographers by name; the photos anonymity and/or official, government sourcing ibecomes a source of authority–and an example of self-sacrifice:

Commander Steichen, although for more than a generation one of America’s most famous photographers, has used none of his own pictures in the exhibition. Nearly ninety per cent of the photographs have been supplied by various departments and agencies of the United States Government…

In fact, the Museum repeatedly mentions that Steichen was tasked by the Navy to organize the show. The context is obviously exceptional–the show opened six months after Pearl Harbor–but the idea that WWII and the US Navy gave birth to the museum blockbuster exhibition is too much for me to process at this late hour.