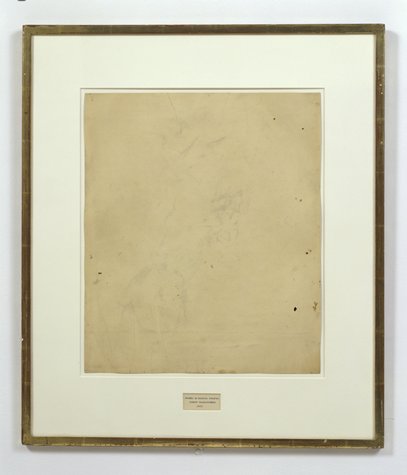

Robert Rauschenberg, Erased de Kooning Drawing, 1953, “drawing | traces of ink and crayon on paper, mat, label, and gilded frame.” via SFMOMA

So the basic question, “What do we really know about Erased de Kooning Drawing and how do we know it?” Is really driven by some recent discoveries that my understanding of the work and its story–its history–turns out to be wrong. Incomplete. Based on some assumptions that should, it turns out, be questioned.

For example, Erased de Kooning Drawing is regularly referred to know as one of Rauschenberg’s most important works, which prefigured or influenced entire movements in contemporary art. But so far, I haven’t found actual evidence that the work was even exhibited before 1973. It’s barely even discussed in the 1960s literature on Rauschenberg, never mind the 50s [It supposedly began shocking the art world soon after its creation in 1953.]

I’m always kind of torn between trying to figure this stuff out by piling on the research and citations and sifting through it, and then posting about it, and just documenting my inquiry, incomplete as it may be, as I go along.

I guess the key here may be laying out what freaked me out, and saying that it kind of blows my mind precisely because I’ve been spending so much time looking back at the relationship and collaboration between Rauschenberg and Johns, and at the stigmatized silence that continues to distort our view and our understanding of their crucial, early work.

A week or so ago, I saw a digitally remastered version of Emile de Antonio’s 1972 documentary, Painters Painting [Here’s the vanilla Ubu version.] De Antonio was a longtime friend of both Johns and Rauschenberg; he helped them get their earliest job together as window dressers for Bonwit Teller. I saw a 1976 note in the Smithsonian archives where Walter Hopps says that Bob called de Antonio “a hustler.” He became a complex and controversial filmmaker with a 10,000 page FBI file. For Painters Painting, he conducted extended interviews with both artists and a critically disparate range of others on the scene [the film was mostly shot in 1970]. According to my MFA brother-in-law, the film is a hilarious staple in art schools, which I think I object to; I may take on the film’s content and form head-on at some point, but not now.

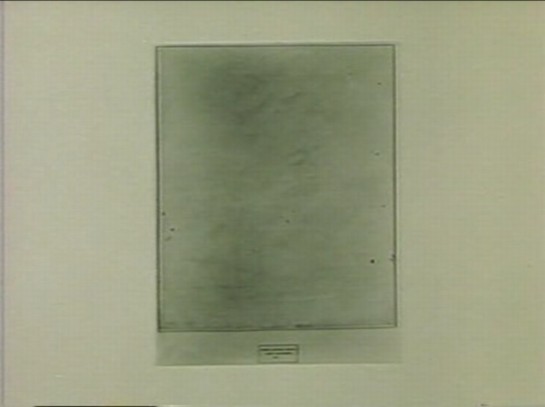

Rauschenberg recounted the story of making Erased de Kooning while sitting atop a ladder in front of the church-like windows of his Lafayette St studio. His delivery is deadpan, deliberately ridiculous, and not a little drunk. De Antonio’s editing is kind of disruptive, but the issue isn’t whether erasing the drawing took “nearly three weeks” or a month, or 15 erasers or 40. The issue is Erased de Kooning Drawing itself:

There’s no frame. And no mat. No nothing, just the drawing. Which feels substantively different. De Kooning’s original sheet appears to be mounted onto the piece of paper onto which the label was drawn. Where the mat now seems to separate the label and the drawing, without it, it seems like one thing. A collage, perhaps, but a joined, unified, self-contained whole.

Which makes the label not just a label, but a text, a set of marks, as much a drawing as the erased marks–or the erasure marks. Rauschenberg’s explanation to de Antonio is different from other, later tellings, and from the neo-dada, Freudian interpretations of others. He seems entirely clear about what he wanted to do:

One of the things I wanted to try was an all-eraser drawing. And, uh, I did drawings myself, and erased them. But that seemed like fifty, fifty. And so I knew I need to pull back farther, and like, if it’s gonna be an all-eraser drawing, it had to be art in the beginning.

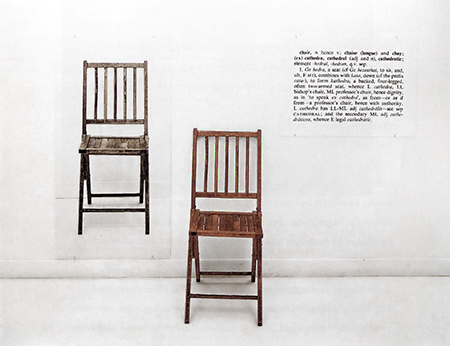

He was trying to make a mark with an eraser. It’s the difference between erasing a drawing, and drawing with an eraser. And when he was done, the result was both an erased de Kooning and a drawing. And the hand-drawn label declared as much. It’s almost a perfectly symmetrical prefiguring of Joseph Kosuth’s One and Three Chairs, made a dozen years later.

But did Kosuth know and react to Erased de Kooning Drawing in creating his piece? Did de Antonio just happen to shoot the drawing while it was out of its frame, or did it look different–was it constituted differently–in 1970? And before? When did it change to the conceptual object, where the label is demoted, no longer an integral element, diametrically opposite but co-equal with the “drawing,” the concept, but now a separated, ancillary presentation device equivalent to mat and frame? Rauschenberg wrote on the back of the work, “FRAME IS PART OF DRAWING,” but I’m not sure that was always the case.

It seems to me that Erased de Kooning Drawing became one thing in the early 1970s, but before then, it was something else.

Previously: ‘FRAME IS PART OF DRAWING’

Next up: looking back at what was said and written and known and shown about Erased de Kooning Drawing before 1973.