Alright, I’ve looked into it and talked to some folks, and while I was and am right to be incredulous, I now feel a little better about Gerhard Richter’s Strip series of digitally printed works Marian Goodman is showing in Paris [above].

So I talked with some Richter collectors, some people who have seen the work in person, either in Paris or elsewhere, and some folks at Marian Goodman, who thoughfully listened to my grave declaration that “I have some real issues with these works,” and gamely engaged it, almost as if a real sale were hanging in the balance, which, obviously, it was not.

The easiest and best first thing to do: ignore Buchloh. I started reading his catalogue essay, and just decided that his ruminations on the implications these digital prints under plexiglass have for the history of facture would just piss me off, so I set it aside for another day. Ultimately, the way I’ve come around to the work, or at least come to see it as credible, is by considering it within Richter’s own practice and history, not as a dubiously hyped innovation of global import.

Invariably, in every conversation, the first reply to my skepticism about these giant pixel extrusions was, “Have you seen the book?”

“The book” is not the slim exhibition catalogue for Goodman’s show, which reproduces 14 examples of Strip, and edition of 72 unique digital prints [53x105cm, mounted on Aludibond] which were chosen from 4,096 possible strips by “chance operation”; as well as the much larger [160x300cm, plexi] works made by combining “selected” strips. [There are also the oil-poured-on-glass Sindbad pictures, but whatever. Off topic. I just want to contrast the different processes, one clearly Cageian, one clearly not, that went into making works out of the system Richter devised.]

“The book” is not the slim exhibition catalogue for Goodman’s show, which reproduces 14 examples of Strip, and edition of 72 unique digital prints [53x105cm, mounted on Aludibond] which were chosen from 4,096 possible strips by “chance operation”; as well as the much larger [160x300cm, plexi] works made by combining “selected” strips. [There are also the oil-poured-on-glass Sindbad pictures, but whatever. Off topic. I just want to contrast the different processes, one clearly Cageian, one clearly not, that went into making works out of the system Richter devised.]

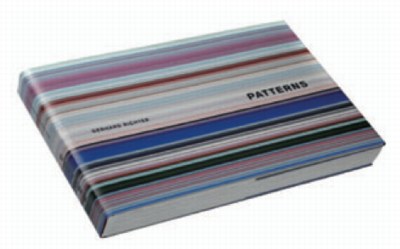

And that system is what’s only really expressed fully in “the book.” Patterns. Divided – Mirrored – Repeated, the massive artist book [41x27cm, 520 pages] published by Walther Koenig in an edition of 800+50, is overwhelming. It consists of 221 spreads showing strips from each of the “twelve stages of division” being mirrored and repeated. I found myself constantly turning back to the key, a diagram of Abstraktes Bild CR724-4, the 1990 squeegee painting which is Richter’s “ready-made” source overlaid with the division and subdivision matrix used to generate the strips. I should have snapped a photo of it, but instead, I’ve simulated it here by hand, with only six divisions, instead of Richter’s twelve:

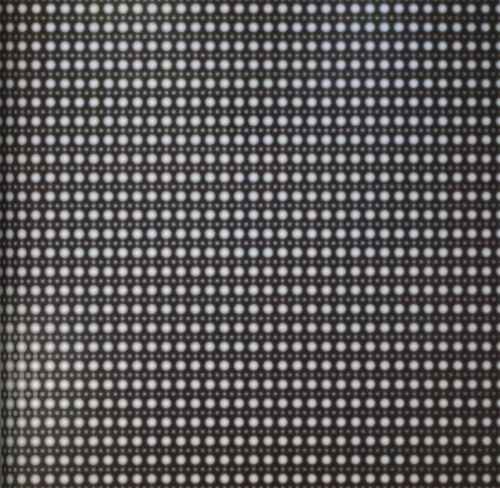

The exponential increase reminds me of the old illustrations of a nuclear chain reaction, which is kind of relevant; Richter has printed digitally manipulated photos of atoms taken with an electron scanning microscope, like his Strontium photomural [below] at the deYoung in San Francisco. Richter conceives of a similarly infinitesimal division continuing here, too, and he apparently only stopped at 4,096 0.8mm-wide strips because the next level of would require magnification to see.

Strontium 2004, 910x945cm, CR888, image via gerhard-richter

Before seeing Patterns, I originally thought these Strips were just pixel-wide extrusions. They are not. The wider, lower-order strips clearly show the mirroring and repeating. Here’s a detail from the cover of Koenig’s 2011 catalogue [pdf] and an unsatisfying page shot from inside. I’d say these are from the 256 and 128 divisions, respectively:

Even on the 2,048 division strips, you can still see the pointy, mini-Rorschach forms. And yet all the stand-alone editions and works came only from the 4,096 level. Which I assume means the static/boring horizontal stripes running across the larger prints should vibrate up close with nearly invisible mirrorings. And since no one has mentioned it, and everyone’s first and last resort to the book instead, I’m going to assume that effect is either not evident, not successful, or not compelling.

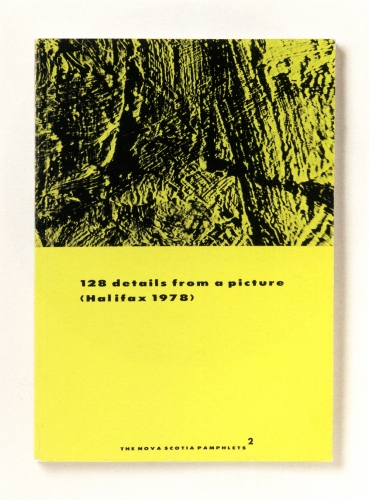

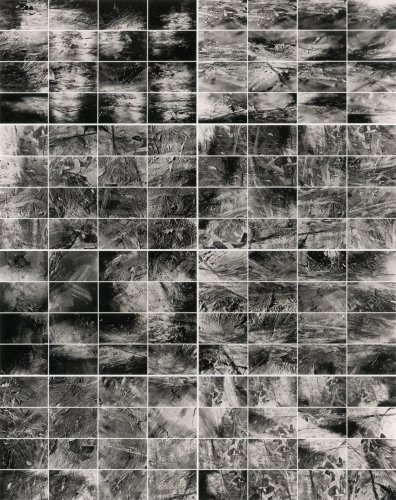

This is not the first time Richter has undertaken a photographic dissection of a painting, of course. He reworks reproductions of his paintings for editions all the time. [He also cut at least one squeegee painting into pieces, which were sold separately, but that’s another story.] His most closely related experiment dates from 1978, where he took black and white pictures of an abstract painting, Halifax, which he used in a photogrid, 128 Photographs of A Picture, and in several artist books, beginning in 1980 with the edition that inspired the title of this post, 128 Details From A Picture (Halifax 1978) I.

Unlike the computational precision that generated Strips, Richter took the 128 Halifax photos “from various sides, from various angles, various distances and under different light conditions.” And yet the end result of both is an apparently randomized, disorientated view of deracinated fragments. A nod to photography’s mechanical “magnifiying vision,” but also a deliberate and thorough sandbagging of its objective, informational idiom.

128 Details from a Picture (Halifax 1978) II, 1998, offset prints, image via gerhard-richter

For years, I’ve loved the Halifax photow way more than the painting. Richter’s expedition across the surface of the painting turns it into a landscape, which his images don’t even pretend to map. Richter must like them, too, because he’s kept reissuing them over the years as new books and editions.

So already in 1978, Richter demonstrates there is no way to reconstitute the image of the original painting from the distorted, incomplete photofragments. Not news. But that might be fine. I bet you could reverse engineer a pretty reasonable approximation of 724-4. Or at least an actionable one. Or an interesting one.

And I would bet that, if you fed a hi-res photo of Halifax and the 128 photos into a computer, it would now be possible to crunch the images and solve the puzzle. Not only could you identify all the parts in the photos, analyzing the light angles and camera distances in a 3D animation program should reveal Richter’s position, sequence, and the path he took as he wandered around the painting with his camera.

Richter was able to stay a generation or so ahead in his flight from intentionality, but it seems to have caught up with him.

Previously: Gerhard Richter Strip Show

Similar but not related: Marion Thayer MacMillan’s Water Pictures

Skip to content

the making of, by greg allen