If I ever get a PhD it will be in the US Pavilion at Expo67 as a gesamtkunstwerk. So much going on there, and in my years of fascination and study of it, it just keeps on giving.

And I am stoked for the Queens Museum’s show, opening to day, on Thirteen Most Wanted Men, Andy Warhol’s short-lived commission for the New York State Pavilion at the 1964 World’s Fair. It sounds amazing, with an impressive amount of archival research and new understanding.

I haven’t seen it yet, but I have been bothered by a line that’s cropped up in several reviews of the show, which makes me think it’s not accidental, calling the 13 Most Wanted Men panels “Warhol’s only public artwork.”

This characterization only holds up if you define public art so narrowly as to make it irrelevant [which is something that happens to public art a lot, actually, but that’s not the point here.] Warhol exhibited work in at least three World’s Fairs in a row–1964 in New York, 1967 in Montreal, and 1970 in Osaka. And the first two were commissions. In fact, I’d suggest that the New York and Montreal projects are so similar, that they really should be considered together. Warhol’s Expo 67 works suddenly feel like a direct response to the controversy in 1964. When faced with the prospect of wading into another political conflict over his subjects, Warhol chose to depict himself.

In 1964, Warhol painted 25 panels–22 with mug shots, 3 blank/monochromes–on 4-foot square masonite panels. The images came from an internal NYPD pamphlet that gave the piece its title: 13 Most Wanted Men. These were painted over in aluminum house paint within two days.

Thirteen Most Wanted Men overpainted and covered by tarp, 1964. Photo: Peter Warner, via Richard Meyer’s Outlaw Representation

Later they were covered with a large tarp. They have since been lost or destroyed. In his incisive 2002 history, Outlaw Representation: Censorship and Homosexuality in Twentieth-Century American Art, Richard Meyer quotes John Giorno’s story about the origins of Thirteen Most Wanted Men, and that the mug shots came from the gay cop boyfriend of another painter, Wynn Chamberlain. 1 [No one’s mentioned it, but I assume this is all in the Queens Museum show. Right? And the show will surely explain why Philip Johnson told Warhol in 1963 not to talk about the sources of the paintings? Johnson, who surely knew as much about power, rough trade, and a man in uniform?]

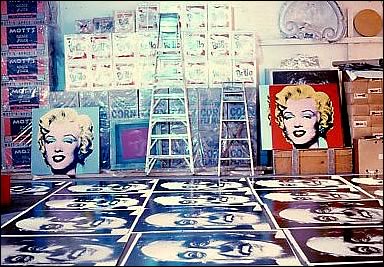

Warhol painted 25 panels with Robert Moses’ headshot, taken from Life magazine, as replacements. Philip Johnson rejected them, and they are also now considered lost or destroyed. [This photo is by Mark Lancaster, who helped Warhol make the Moses panels and much else. There’s a great interview with Lancaster at warholstars.org.]

During the Summer of 1964 Warhol reused the screens to create paintings on canvas of the 13 Most Wanted Men, which Lancaster cropped and stretched. Nine of these are currently in the Queens Museum show.

In 1964 he began making the Screen Tests, which were inspired both by the Thirteen Most Wanted mug shots and the photobooth pictures Warhol began using in 1963. He created Most Wanted series of women and boys as well.

Warhol visiting Expo 67 with the de Menils, that’s John de Menil at left, not Buckminster Fuller, as some online sources would have it. image via menil.org

In 1967 curator Alan Solomon commissioned Warhol to make large paintings for the US Pavilion at Expo 67. Warhol created eight giant Self-Portraits. They are 6-feet across and based on a photo by Rudy Burckhardt. Six of them were installed in Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic dome, above Jasper Johns’ Dymaxion Map. Four of them are visible above, in a photo taken during Warhol’s visit to the Expo with John & Dominique de Menil. The one on the lower right is now in the Tate Modern.

If the Thirteen Most Wanted Men censorship was really as concerned with vice, power, and the homosexual gaze as Meyer argues, then Warhol’s uncensorable Self-Portraits read like an act of defiance. For his 2nd World’s Fair, Warhol didn’t shrink from political conflict; he met it straight on and came out on top.

1 Update: I just came across a story by Lucy Sante about Thirteen Most Wanted, which he published in 2009. It is, I assume, a fictional encounter with a retired NYC policeman who had the idea for a Ten Most Wanted list stolen from him by a fellow cop, who became lovers with a young Warhol, and then years later, while guarding the World’s Fair, saw his Most Wanted Men idea stolen again by his ex. Hmm. I think someone had better talk to John Giorno.

Skip to content

the making of, by greg allen