The Smithsonian has added the Hirshhorn Museum’s audio archive to their digital library collection, and it’s great. Too often in the art world, what happens in Washington not only stays in Washington, it’s forgotten in Washington. So it’s unsurprising that the Nation’s Attic has interesting, even important stuff in it that really should be dusted off.

One of the first recordings I headed to this weekend was a lecture by Felix Gonzalez-Torres, in association with his Summer 1994 retrospective. I hadn’t heard Felix’s voice in almost 20 years, and I’d never heard him talk at length about his work. I was not prepared, either, to hear him say he was getting tired about an hour into the recording. After that, I couldn’t not hear his exertion to complete what was clearly a difficult, but imperative task.

It turns out I was also not prepared for how unfamiliar his work sounded in his own words. And how different his practice was from the received, sort of calcified, canonical understanding of it. The things he emphasized vs the things we saw or now see as being elemental.

Felix read part of his 1993 interview with Tim Rollins, which we know. But he also talked along to a selection of slides, which I tried to follow along in my books. Easily half the works he discussed were not included in ostensibly definitive catalogues and anthologies. Many had different titles. Some weren’t illustrated.

All of this is of a piece with Felix’s work, though. He would change the titles of pieces. Works he showed and sold were, near the end of his life, recategorized as “additional materials” and “non-works.” But some things, installations and site-specific projects in particular, seem to have been sorted out of his canon completely and/or ignored by critics.

We work with what we have, but we too often don’t see what else there is. And when we find out we’ve been using incomplete or inaccurate info, we’re slow to adapt.

So here’s a single example. It’s a piece Felix started his Hirshhorn talk with, and which he said “is a key to a lot of my work, and also the way I am.” And it’s piece I’d never heard of or seen, whose bare, incomplete, and contradictory references in the record so far I have completely overlooked. The artist called it “Untitled” (Quatrenium).

Here’s what he had to say:

This is a piece from 1989, sorry, 1988, called Untitled (Quatrenium) I put this one first among many slides because I think this is a key to a lot of my work, and also the way I am.

To me, one of the biggest compliments I get is when people tell me, “Oh, I went to see your show, but there was nothing there.”

And that’s what happened with this sculpture. What you see here is four black–actually what you see here is two black plexi sculptures that were put downtown in New York, sponsored by the Lower Manhattan Cultural Center [sic, Council].When I first got invited to do this show, or this sculpture, I was very happy, and I thought, oh great, to put a sculpture in a park. But only in New York, a park is a piece of asphalt in the middle of an intersection. So when I got there, I said, “Wow, this is a really happening park.”

And what I wanted to do first was to put up a big white flag with a flagpole, and I wanted the flag to be white because this is an intersection of different communities, and I wanted all of them to reflect their own ethnic–their colors on this flag.

But I wasn’t allowed to by the Parks Department because a white flag, for them, meant surrender. So– [audience reaction] I know, stranger than fiction, isn’t it? So they allowed me to put these four big black squares. And I thought it was going to be covered with graffiti and defaced, but actually, they weren’t. They stayed up for the whole three months, and I think that’s an achievement in New York, itself.But again, the compliment I got the most was people said, “Oh I went to see the sculptures; they were not there.”

There is almost nothing online or in any of my books or catalogues about the work, except for its opaque mention in the artist’s official bio/timeline: “Quatrenium, Petrocino Park [sic], NY/ (June 7 – Sept 12).”

Petrosino Park is the fenced in part of what used to be known simply as Kenmare Square, the narrow triangular space where Center Street merges with Lafayette. The colors that would have been projected onto that flag, then, would have come from Chinatown, Little Italy, and SoHo, the center of the art world at the time, which, though a tribe, was not technically an ethnic group. Petrosino Park is named after the only NYPD officer to be killed abroad, Lt. Joseph Petrosino, who went to Sicily to investigate the Mafia in 1909. [In June 2014, Petrosino’s murderers were finally identified as part of a massive mob crackdown in Palermo. Frankly, I can see why the city would oppose a white flag being raised in a park on the Mob’s doorstep named after the victim of a still-open case in a police killing.]

Kenmare Square was definitely a sketchy dump, though. According to The Villager’s history of the site, the LMCC began programming temporary art installations in 1984. The Storefront used it for some temporary projects before it finally got a fancy makeover in 2007. Then last year the art site was taken over by Citi Bike.

And now I see an entry in the catalogue raisonne’s registered non-works appendix I’d never noticed before:

XI

“Untitled” 1989

quatrenium and plexiglass

48″ x 70″ each

Notes: Project for Public Art Funds, New York

ARG # GF 1989-14

In some ways, Felix’s body of work seems to thwart the entire premise of a catalogue raisonne, yet the one published in 1997, barely a year after Felix’s passing, is an invaluable, if incomplete, resource. Maybe it’s best to view it as an accurate reflection of the perception and information and material available at the time. But I can’t find any description of what material quatrenium is. Those don’t sound like squares. And the Public Art Fund switchup turns out to be relevant.

Because the LMCC put “Untitled” [(Quatrenium)] on view in Little Italy at the same time the Public Art Fund installed “Untitled” [above] at Sheridan Square. The billboard, the artist’s first, took the form of one of his black photostat text works, and was associated with the 20th anniversary of the Stonewall Rebellion. It’s no. 65 in the CR. The New York Times reviewed both public art installations together, Felix’s first review as a solo artist.

Mr. Gonzalez-Torres has attached four blank black Plexiglas squares to the fence around Petrosino Park, a grimy little triangular enclosure in TriBeCa [sic]. The squares welcome graffiti, which can easily be erased. The Plexiglas plaques function both as lenses that make people look at the homeless who use the ”park,” and as mirrors that deflect attention onto the people observing them. In a quiet, almost inconspicuous way, they alter the way the site is seen.

So formally similar works focused on visibility and marginality in public, shown simultaneously across town from each other. One becomes an icon, the other basically disappears. Yet five years after he made it, the artist mentions the latter, the one-off, as the key work. Why? Because of the work’s beyond-ninja invisibility? Are the greatest works of art the ones no one ever even knows about?

Following this “Untitled” (Quatrenium) thread leads to two other interesting projects: “Non-work” no. XIV in the CR turns out to be, “Untitled” (Second Quadrenium 1984-1988), a 1990 set of four dark green monochrome paintings similar to “Untitled” (Forbidden Colors). A quadrennium [two n’s] is a four-year period. FWIW, the one in Felix’s parenthetical title corresponds to Ronald Reagan’s second term. Those paintings have an inventory number, but their status and location are not given. I made a mockup of the piece from the (Forbidden Colors) jpg.

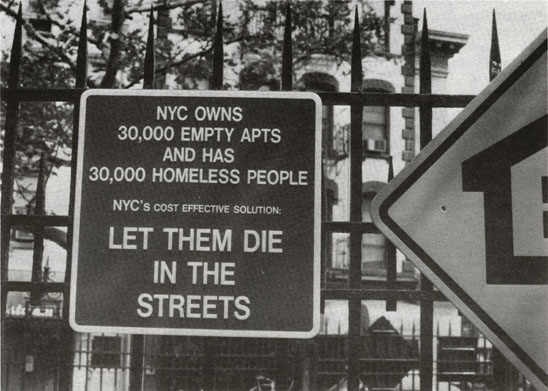

Also in 1990, the AIDS activist art collaborative Gran Fury basically re-performed Gonzalez-Torres’ two public works. The group responsible for the design and dissemination of the “Silence = Death” logo put up billboards calling for federal government action on the AIDS crisis. And on the fence at Petrosino Square they installed enameled steel signs criticizing the city’s non-response to homeless residents with AIDS. The project was brutally titled, “Let Them Die In The Streets.”

image via Robert Gober’s interview with Gran Fury in BOMB Magazine

And this is just one work. There are curtains and mirrors, pours and stacks, a sound installation, and his incredible show at Andrea Rosen which changed every week titled, “Every Week There Is Something Different,” which Carol Bove recreated for her curatorial collaboration with Elena Filipovic at the Beyeler last year. So I guess we’re not completely lost.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres Lecture, June 27, 1994 at the Hirshhorn Museum [library.si.edu]