We’ll talk about this in the morning.

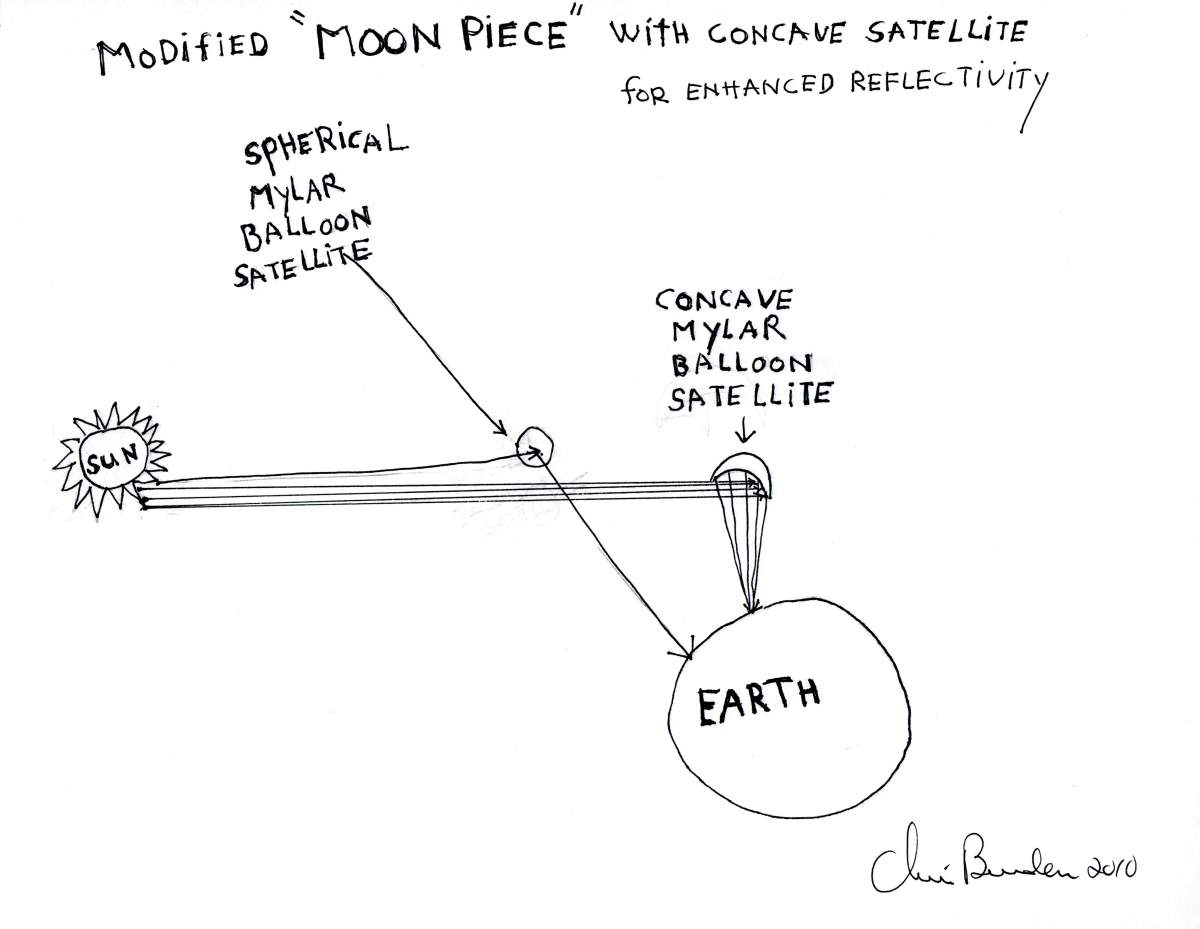

Chris Burden, Modified Moon Piece, 2010 image: manpodcast

MORNING UPDATE A WEEK LATER, BECAUSE APPARENTLY IT TAKES LONGER THAN ONE NIGHT TO PROCESS THIS

November 2011: This was sitting right there in the first episode of Modern Art Notes Podcast, waiting. And even though he wouldn’t tell me who the guest was, Tyler had been goading me before the launch, that I better listen, there is a surprise. Because he knew about the satelloons.

And I did not know about Chris Burden’s unrealized 1986 proposal for The Moon Piece, which is basically to launch the biggest possible spherical inflatable mylar balloon satellite into orbit.

Which was basically the same idea I’d had four years earlier. Or nineteen years later, depending on who’s counting.

Or was it? Maybe it’s fine? Maybe it’s different? Relationship status: it’s complicated. Green teed the question about Burden wanting to build something like the Eiffel Tower. And in discussing The Moon Piece Burden said it could be a giant spherical balloon or an even more “giant parabolic mirror you could control.” Which, if you made it about “the size of Lake Havasu,” [78 km2, btw. -ed.], you could use to “light [all of] New York from above.”

So maybe it’s not a satelloon at all, then. And he’s talking about something permanent, and big enough to light cities from space. This sounds like the Russian thing. Except it can’t be, at least not originally. Green cited a 1988 interview with Paul Schimmel as the source for this proposal. And solar mirrors didn’t really show up until the 90s. Russia ran a proof-of-concept solar mirror program called Znamya from 1992-99 which, it was hoped, would boost solar power production and bring light to darkest Siberia. But it only had one success: a 20-meter-diameter mirror launched in 1992 which produced a 5km-wide beam as bright as the full moon. Later, scientists at Livermore Lab proposed massive solar mirrors as one extreme technological approach to geo-engineering humanity’s way out of the climate change crisis. So this solar mirror aspect is different, maybe an adaptation, an addition, and it shows the artist was keeping tabs on things. But Burden’s original The Moon Piece idea is/was a satelloon.

It turns out Burden first pitched The Moon Piece in a letter to Edward Fry, who was co-curating Documenta 8 (1987) The letter was [first?] published in the appendix of the amazing 2005 monograph, Chris Burden. [Which I bought in 2008, but didn’t read all the way, even after getting more into his work in 2009.]:

[The satellite’s] “only function and purpose would be to reflect light back to earth. This special satellite would function much in the same manner that our present moon reflects sunlight. I foresee that this huge satellite could be manufactured out of fairly inexpensive, highly reflective Mylar film and be carried into outer space in a deflated state (like an uninflated balloon).

…

The Moon Piece will be highly visible to the naked eye and appear, in relation to the pin points of starlight, as a bright automobile headlamp moving rapidly across the night sky, one-fifth to one-tenth the size of the moon. The most sophisticated and the most primitive of cultures will be aware that something has changed in the heavens.

…

This is not simply a conceptual project. This project is technically feasible and to function as a work of art it must be actualized.

…

Obviously more research and information needs to be done on the specifics of the Mylar balloon such as size, thickness of Mylar, weight, etc., but I believe that The Moon Piece is physically and financially feasible given enough energy. If this idea, of putting into orbit a highly reflective satellite that would light up the heavens, could come to fruition I believe it would well be worth the effort.

On the one hand, it’s nice to feel like you’re on the same wavelength with someone whose work and career you admire. On the other hand, damn.

But some things stood out. Like Burden “foreseeing” the possibility of the satellite’s existence, and not knowing any of “the specifics.” Is it possible that Burden really did not know that these exact objects had already been created and deployed in the 1960s, when he was a teenager? I can’t believe it. Was it not important to his concept, or his pitch, to reference their historical sources, or their current non-art uses? Apparently.

And he adapted The Moon Piece, which began with the assumption that after 20 years, an inflatable satellite could be bigger, and after 30 years it could be bigger still. Or it could use future-state-of-the-art technology and be a mirror as big as a lake. Burden’s constants were big, reflective, and in space. But other than that, the 2010-11 version didn’t sound any further along than 1986’s.

A few months later (in 2012) I was working on making and showing a satelloon at apexart in New York, and I uncovered aspects of satelloons and their history that mattered. The concept had originated with none other than Wernher von Braun, who proposed, not a new moon, but a new, “American Star” which would awe the lesser nations into supporting the US in the Korean War. Von Braun wrote that in a widely published Time | Life book on space travel. Burden’s language about “primitive cultures” knowing “something has changed in the heavens is straight from von Braun’s pitch. The NASA engineer who had claimed the most credit for Project Echo came up with the idea at von Braun’s V-2 rocket conference. It was OK’d after Sputnik because US military leaders wanted a visible satellite would normalize people to the presence of spy satellites and surveillance.

This is context I only pieced together after five years of researching. Burden missed or omitted not just this, but the very existence of Project Echo, when he proposed Moon Piece for Documenta1. Would it have turned up in Kassel? How would that’ve gone over? I can’t even imagine.

Except that I did, and I still do. My apexart experience has made me very wary of satelloons, which are seductive, but also politically problematic. Their beauty and surface make them impossible to ignore, which makes it worse. I’ve also found that where I once felt daunted and insecure about having the same idea as a major artist I admired, I am OK with it. Partly because I realized my project is better.

And that, plus a $25,000 Marquis Jet card, can get you to Basel. Burden nailed it the first time: this is not a conceptual project, destined merely for Hans Ulrich’s files. It must be actualized. And so it’s especially unfortunate that Burden, whose genius was superlative physicality, can’t see The Moon Piece in the sky himself.

After hearing about The Moon Piece, Green’s follow-up question was whether Burden would be OK with people “mining his files” to produce his unrealized projects “after you’re no longer with us.” It’s a conversation that obviously sounds very different now than it did in 2011, which is just one reason it’s taken me more than a week to write this blog post. “if somebody wanted to do that after I’m not around, that’d be fantastic,” Burden said. “I think that’s why people become artists, you know. To have a life beyond them. I mean, it’s a way to become immortal.”

The Project Echo satellites stayed in orbit for five and eight years before gravity pulled them into the earth’s atmosphere. It’s not quite immortality, but it’s a start.

Related, devastatingly: Chris Burden dies at 69 [latimes]

2007: If I were a sculptor, but then again

2013: Exhibition Space [apexart.org]

Listen to the entire discussion between Chris Burden and Tyler Green on Episode 1 of MANPodcast [manpodcast]

Or listen to the 3:00 MANPodcast excerpt where Burden & Green talk about The Moon Piece [dropbox greg.org, 4.6Mb mp3]

[1] What did Burden end up showing in Documenta 8, anyway? I have found him listed in the participating artists on Documenta’s own site, as showing “audio”. Of Burden’s four pre-1987 audio works, only The Atomic Alphabet and Send Me Your Money, both 1979, seem likely. For his part, the artist’s official CV only mentions Documenta 6, in 1977. Fry was the American co-curator on both.