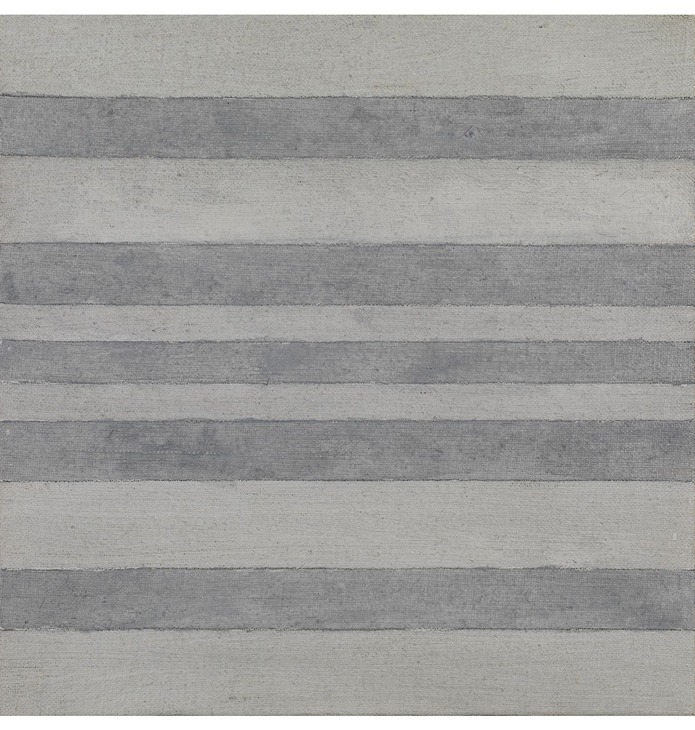

[Not?] Agnes Martin, Day and Night, 1961-64, enamel on linen or acrylic on canvas, 72×72 in., currently Collection The Mayor Gallery, London

I was already soaking in some Agnes Martin-related research when the news broke last week of a lawsuit filed against the Martin catalogue raisonné, its authentication committee, and Arne Glimcher, the artist’s longtime dealer, who controls it all. And so I did some preliminary digging and looking, and oh boy, unless you own an off-market Martin, is it an entertaining mystery.

London dealer James Mayor is suing over the rejection of 13 works Mayor and his clients submitted for inclusion in the CR. There is one big, 1960s painting, two 1950s works on paper, and ten small canvases, all from 1974. Mayor sold the works between 2009 and 2013, and ended up buying them all back in 2014-15 when the unexplained, unappealable rejection letters started coming from the anonymous committee, headed by CR editor Tiffany Bell. [Technically, everything was handled by Agnes Martin Catalogue Raisonné LLC.]

I am not a lawyer, but as a legal claim, the case seems rootless and lost before it starts. As a lens for understanding how the art world works, though, and for considering how Martin’s legacy plays out, I see two big questions in it: 1) the art, and 2) the CR.

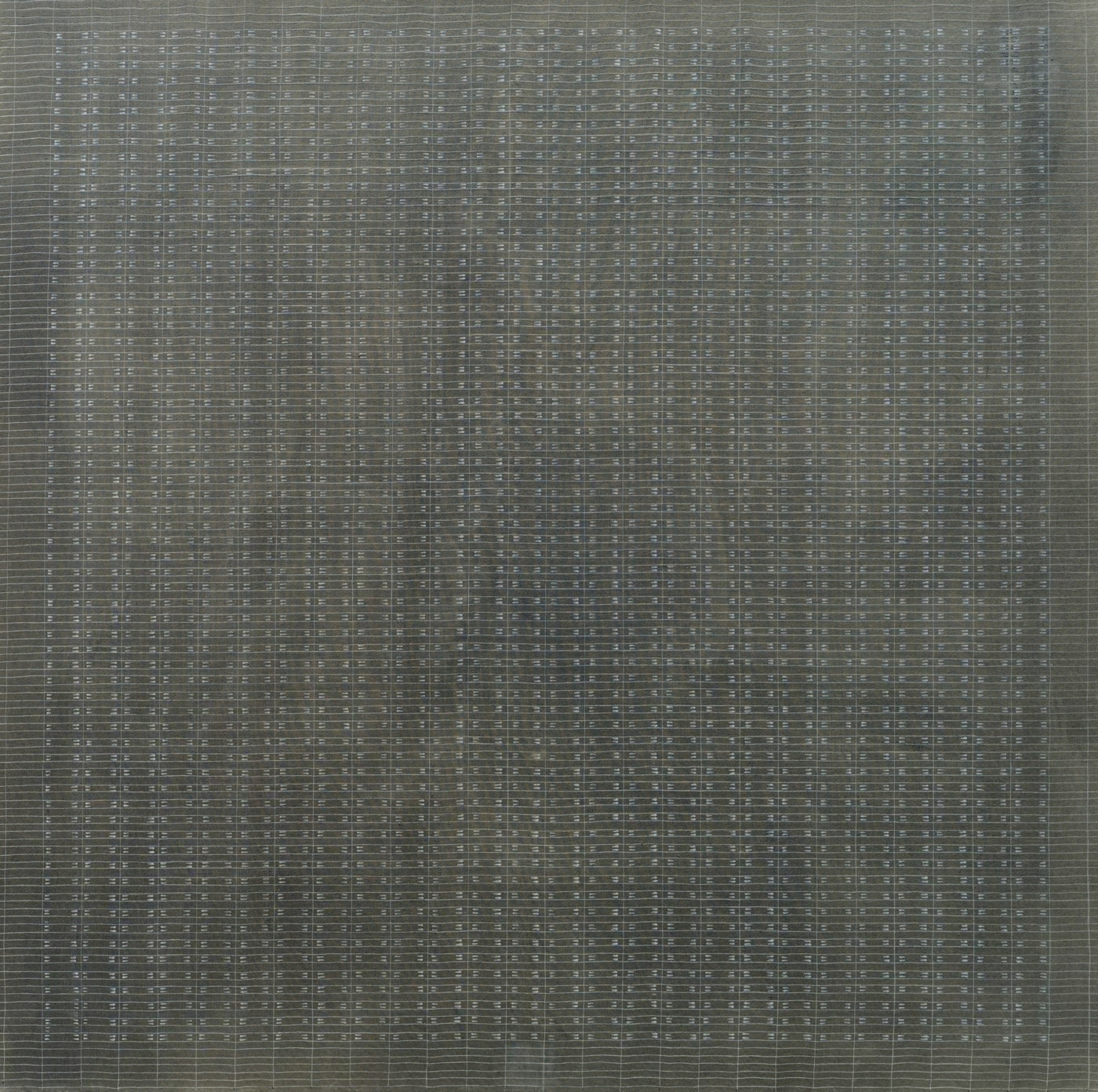

[Actually] Agnes Martin, White Flower, 1960, oil on canvas, 72×72-in., Guggenheim Museum, gift of Lenore Tawney, 1963, img

Let’s start with the art. The big painting, Day and Night, is dated 1961-64 (or 1967?), and sounds like an iconic early grid. Mayor sold it to banker Jack Levy in 2010 for $2.9 million, which sounds reasonable for the time, and for a work of significance, maybe even a good deal. Levy submitted it to the CR in 2014 with no documentation, apparently, but with provenance info and a breezy backstory that, it has to be assumed, came from Mayor. [Because when you buy an artwork by a modern master from a venerable dealer like Mayor Gallery, you can be assured of its authenticity. As Levy would know, since he also bought five forged paintings from Knoedler, including a Pollock he returned in 2003 when it couldn’t be authenticated.]

After the painting was rejected with no explanation or recourse in 2014 (as the submission agreement clearly and repeatedly states), Mayor bought it back and resubmitted it last year with such corrections as: a different medium [“enamel on linen” became “acrylic on canvas”]; and a different provenance, bolstered by vintage photos, emails, an old exhibition checklist; and an atmospheric radiation analysis that dated the canvas to 1954-57. The only images released so far of Night and Day are in photocopies of the background of snapshots and the conservator’s report. It’s dark, with white vertical grid elements bisected by a white or unpainted horizontal line. [top]

white line, runnin’ thru my mind…

image via Mayor v Martin et al

Referring to a Sept. 1975 interview transcript I can’t find yet, Levy said Martin recalled Day and Night as the “sister…to White Flower [1960, above] that is in the Guggenheim in New York.” And I can see the connection. Or at least imagine it.

Day and Night is signed “to Delphine,” which Levy said was because Delphine Seyrig, Jack Youngerman’s wife, owned it, then sold it to Lenore Tawney when she moved back to France. “Agnes Martin then bought the painting back from Lenore Tawney for ‘twice what she had paid’ when Lenore needed money at a later date,” wrote Levy, without any citations for any of that. But it’s all specific enough it had to have come from Mayor.

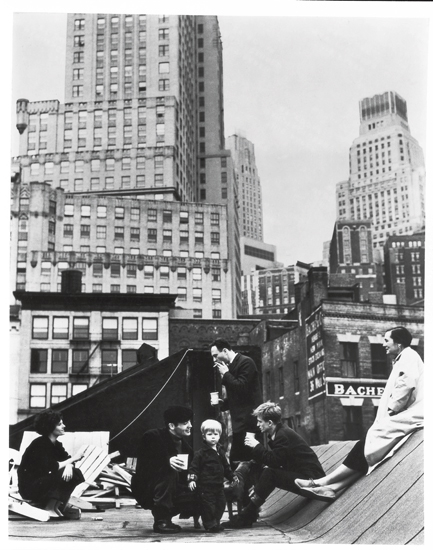

that photo, with Delphine Seyrig, Robert Clark [Indiana], Duncan Youngerman [the kid], Ellsworth Kelly, Jack Youngerman, and Agnes Martin, by Hans Namuth, 1958

Yet when Mayor resubmitted Day and Night he included a 2014 email from Youngerman saying, “I am sure that Delphine never received this painting from Agnes, the dedication is merely an affectionate ‘homage’.” Which, how did he not ask this before? Youngerman also says he never saw the painting, but that “judging from the photo, I don’t think that any faussair [sic] could conceivably have created such a painting.” Faussaire is French for forger, so I’m sure this email put the committee at ease.

According to Mayor’s new, corrected provenance, Tawney acquired Day and Night “before 1971,” when an exhibition checklist from the New Mexico capitol building lists the work (as c. 1967) and Tawney as a lender (though of what, it does not specify). Then “by the mid 1970s” Tawney gave or sold the work to ceramist Toshiko Takaezu (listed as Toshika Takaesu), and then in the “early 1980s” the work came to Samuel Adams Green. All roads led to Samuel Adams Green.

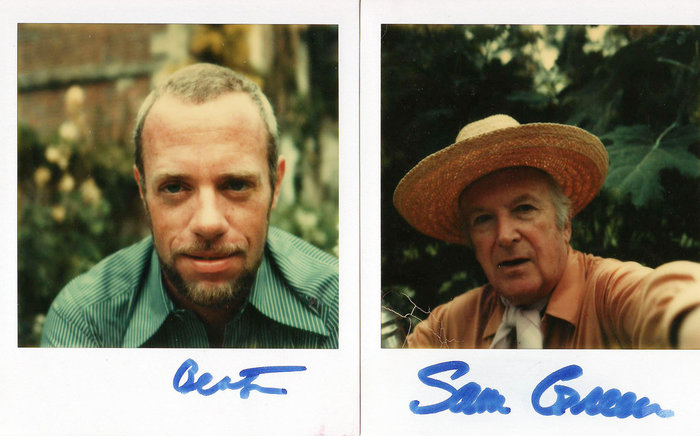

Cecil Beaton photographed by his traveling companion Sam Green and vice versa, via nyt

Green was Mayor’s source for all the Martins that the AMCR rejected. So who is Green? He either a cultural impresario of the 60s Pop and Minimalist zeitgeist and friend to the grandest artists, celebrities and aristocrats of the day, or he was a twinky walker/bullshitter who boondoggled his way through the Factory, coasting on connections, and taking credit for stuff he didn’t do. Or really, why choose? Game recognize game.

Green died in 2011, and for purposes of this blog post, it’s worth noting that he was the director of the ICA in Philadelphia who put on the 1965 Warhol retrospective-turned-riot; he was around NYC on the art scene in the 60s and 70s; and he worked as a private dealer. But he also lied about so much stuff and left so little paper trail that he is a pretty weak link in any provenance chain.

Two of his claims involve saving Agnes Martin’s career. Twice. Green said he was there in 1967 when Agnes Martin gave up painting. To Nancy Housler, biographer of the collector Emily Tremaine, Green said:

I remember once Agnes Martin, who was disgruntled with the art world but not with me, gave me the keys to her warehouse where she had 20 or 30 paintings on rolls on the canvas. She hadn’t even bothered to stretch them. She said, ‘Sell these, all of these for me, I want $20,000 each for them and I want them in the best collections.’ which is what I did. But Emily and I had to go to this warehouse and unroll the paintings on the floor.

Where to even start? Literally every piece of this story raises eyepopping questions. But wait, there’s more.

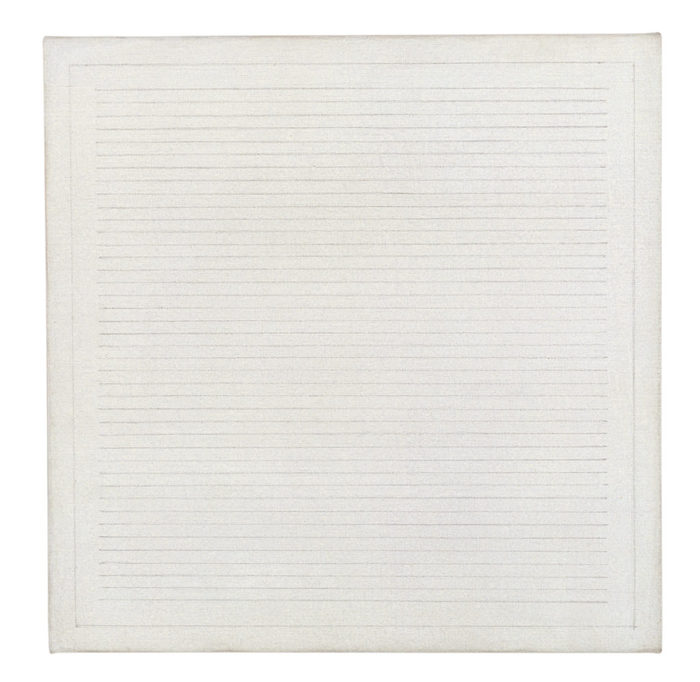

Agnes Martin [or not?], Untitled (Solitude), 1974, acrylic on linen, 12×12 in., via Mayor Gallery, image: Foundation de 11 Lijnen

Green also used to say he was the one who got Agnes Martin to start painting again. Here’s how Mayor put it in the description of a 2012 group show at Foundation de 11 Lijnen in Belgium:

After Agnes Martin left New York in 1967, she withdrew to the desert of New Mexico and stopped painting. Samuel Green, the former director of the ICA in Philadelphia, and a good friend, insisted that she should pick up her paintbrushes once again. I won’t let you go, he warned, before you return to painting. And in 1974, Agnes Martin painted for the first time in seven years.

Of the 14 small paintings in the show, which I read to be the first paintings Martin made since 1967, at least 10 went to one buyer, who submitted them to the AMCR, who rejected them all.

Nancy Princenthal’s biography of Martin and Arne Glimcher’s monograph/memoir of his relationship with Martin both only mention Green’s presence once, at a Coenties Slip party, with Sam Wagstaff. For his part, Wagstaff, who was curator at the Wadsworth Athenaeum, collected Martin’s work and kept up a steady correspondence with the artist during her hiatus. And Martin’s letters to Wagstaff are now in the AAA. Here are some relevant highlights:

Agnes Martin, The River, 1965, oil on canvas, 12×12-in., Collection Louisiana Museum, image: artnews

From May (1971 or 72?):

Dear Sam, It is very generous of you to send your painting to Germany. I particularly like the ones you have. Wish you would send the early River on unsized canvas out of storage [1963, 12×12, btw. -ed.] Documentary 5 [sic] must certainly be a big show.

From Dec. 1971:

I did release three paintings to you but I’ll write again releasing The River. I hope that is the river on linen. You should have chosen The Ages. I think it is a good one too. It doesn’t cost me anything to store the others. Can’t think of selling until after the Philadelphia Show but thank you. Think I will be able to make the little paintings. Still terrible slow pace of one a month.

Wait, Martin was painting months before her Jan. 1973 show at ICA Philadelphia organized by Suzanne Delehanty? Also, there *were* paintings in storage, though we only know a couple by name.

Also from May 1972:

Dear Sam, All the paintings in Santini’s [the longtime New York moving & warehouse company] are available. You are wise to take The River, You do have enough for a show. Albert Fine, who knows the “assistants” wrote to tell me that both Pace & Castelli are ready to show them if you are ready to sell…Bob [Elkon, her former dealer] will not like it but it will help him (other customers) if you do show. He’s always against things that I know will be good.

Sam Green and Sam Wagstaff were frenemies. They organized Tony Smith shows together/at the same time. [Green bitched about Wagstaff stealing credit for discovering Smith.] Wagstaff overstayed at Green’s Fire Island shack. And in the Summer of 1972, when Wagstaff was shipping his Martins and her Martins off to Kassel, Wagstaff met Robert Mapplethorpe. Later Green falsely claimed he’d introduced them for spite. [These and other wild tales are in Philip Gefter’s 2014 biography of Wagstaff, who went on to transform the photography world.]

I’ve been reading about this Martin scenario for almost a week, and this is literally coming together as I type, but now I wonder if the Sams were both involved, or if one Sam was just taking the other Sam’s stories for himself. When Green was supposedly selling paintings for $20,000, Martin and Wagstaff wrote about how grateful she was that he bought five drawings for $100 apiece.

Meanwhile, the sidebar continues to grow, with insights like it’s possible Martin had not abandoned painting, or had taken it up again earlier than is understood, as early as 1972. And the letters support what Christina Bryan Rosenberger, who just wrote a book on Martin’s early career, said on Martin’s early career on MAN Podcast: that even in BF New Mexico, Martin stayed connected to art world friends and colleagues, and that she left no archive of her own, and in fact seemed to put as much effort “covering her tracks” as she did on destroying work she didn’t like.

Which brings me to Big Question #2: the CR. How is this going?

In his lawsuit, Mayor claims that the AMCR Committee’s refusal to include an artwork is “therefore recognized in the world wide marketplace as a conclusive statement that the artwork is a fake.” But that is not technically true. The last paragraph of the examination agreement reserves the right for AMCR to change “any decision” at “any time,” and to add or “withdraw, edit or amend its opinion” on any work “without any legal effect or consequences.” So accepted work could come out, or, conversely, rejected work could come in.

Mayor’s complaint notes that before resubmitting Day and Night to the committee, he had “several discussions with defendant Tiffany Bell” in which he “questioned Glimcher’s bona fides and whether the art world should refuse to cooperate and support [the AMCR.]” He was also “concerned that Glimcher’s obvious conflicts of interest and the longstanding frictions and disagreements that existed between him and Glimcher, prevented an objective and fair vetting of submitted artworks.” He did not elaborate.

And when his works were rejected again, the AMCR didn’t elaborate, either, and they ignored all of his followup requests. Mayor did get a letter from AMCR’s lawyer, though, stating that, “Other submitted works referencing The Mayor Gallery in their provenance raised material legal concerns.

“If you bear personal responsibility for the nature of these works and their questionable provenance, be advised that you will be held responsible for compensatory and punitive damages.”

When I started digging into this story, I wondered if the works were forgeries. Then I wondered if they might have been works Martin painted, which she’d later disavowed. But they’re also signed. Or maybe Green had acquired the works in some sketchy way. [Except for Day and Night, whose shifting provenance had to appear less than solid to the Committee, Green purportedly got all the other works directly from the artist.] Then I marveled at Green’s propensity for hilarious lying, and again at Mayor’s extremely elastic research, and I wondered if they simply raised too many questions, inevitably tainting any works they’d touched.

But as Mayor’s suit angrily points out, Glimcher, Pace, the Agnes Martin Foundation [i.e., the Estate], and the AMCR [via ACMR, LLC.], are entirely under Glimcher’s control. Which means if you want to play in the Agnes Martin market, you are going to play by Glimcher’s rules. And nothing in Mayor’s suit, at least, is going to change that.

New Authentication Lawsuit Filed Against Agnes Martin Catalogue Raisonné [art law report via @aservais1]

London’s Mayor Gallery files lawsuit against Agnes Martin Catalogue Raisonné [theartnewspaper]

Search NYSC for all court filings in Mayor Gallery v Agnes Martin Catalogue, index no. 655489/2016 [iapps.courts.state.ny.us]

[April 2018 update: Mayor’s messy case was dismissed, though he has a right to refile part of it within 20 days, and he has been ordered to pay Pace/Martin’s legal fees. He has taken back two works, and has agreements to take them all back if/when the case failed. So maybe they’re available? idk]