Some day I will learn to visit grupa o.k. more frequently in order to better time my awe to their discoveries, but that day is not yet. And so I just saw their January post of Walter de Maria’s contribution to Willoughby Sharp’s foundational exhibition Earth Art, staged in 1969 at Cornell’s White Museum.

Here is how that piece went down, and the Ithaca Journal’s image of it, as told by Amanda Dalla Villa Adams in a 2015 essay on De Maria’s sound works at the Archives of American Art. Did I mention the title of the piece yet?

When Sharp asked De Maria to participate in the show, the artist wrote back a letter outlining his project. Proposing to exhibit a mattress and an audiotape of crickets in the room (presumably Cricket Music), Sharp promptly rejected the work, stating, “in no uncertain words that each artist in the show had to touch dirt.” In the wake of Sharp’s decision, an alternative proposal was submitted according to the curator’s requirements. Sharp later described De Maria’s installation of the accepted work:

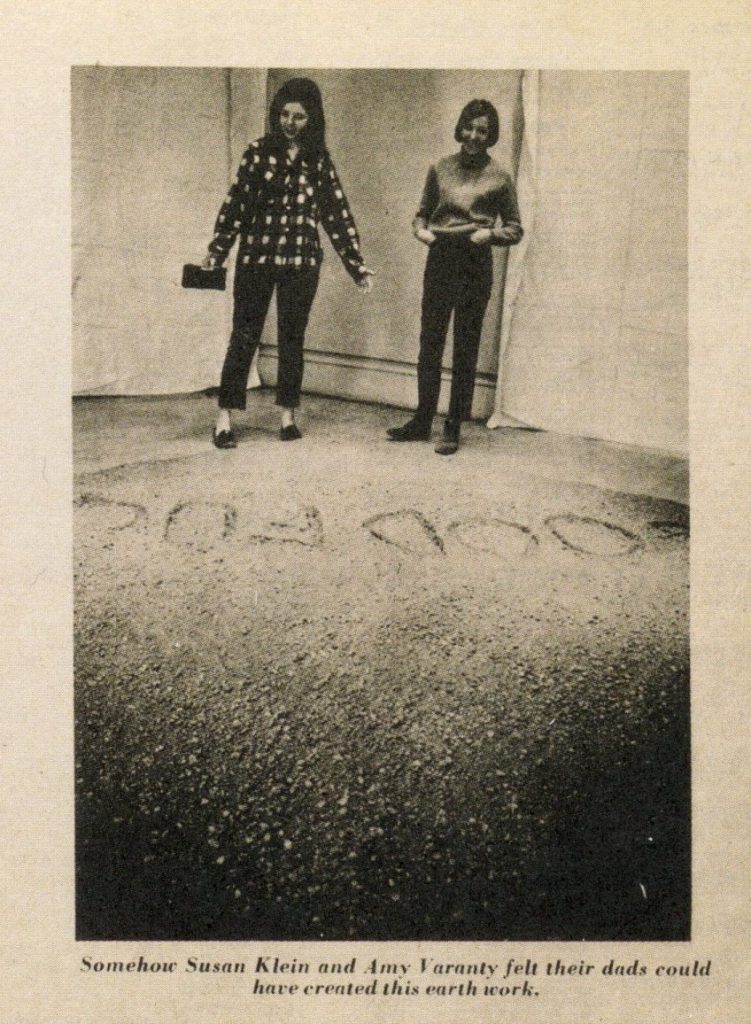

[De Maria flew in and during the opening—and there were hundreds of people going through the museum—he had the cartons of earth emptied into the center of the floor, and then he got his only tool, which was a push broom, with bristles and a long handle, and he pushed the earth into a carpet that was about two inches high. And when that was done to his satisfaction—he did it very meticulously—he took the broom and turned it so that the end of the broom handle became a marker and very slowly, across this tablet of earth, he wrote G-O-O-D, and then F-U-C-K…As soon as Tom Leavitt (then director of the Andrew Dickson White Museum of Art at Cornell University) saw that, and realized that there were kids at the opening as well as the president of Cornell, they cordoned off the room, put up Sheetrock, and the next day the piece was swept up and dispersed.]

This long retelling of Sharp’s story is important for reassessing De Maria’s earth-based projects and reinserting the foundation of sound to his overall career. According to Sharp, the earth carpet was Plan B; dirt became essential because of curatorial limitation. More akin to his much earlier ironic game pieces, such as Boxes for Meaningless Work (1961), where the viewer is constantly reminded that what he or she is doing is meaningless, Good Fuck is an irreverent jab at the art community.

The title itself is a gimme, obv, but it’s the idea of dirt as De Maria’s Plan B and curatorial imperative that sticks with me. Also as Adams’ footnotes point out, Sharp’s timeline doesn’t quite compute. In her 2013 review of MOCA’s Land Art show, Suzaan Boettger notes that De Maria’s piece stayed on view for several days, but when the university came after it, he and Michael Heizer both pulled their works in protest. [Boettger brings it up because they both refused to participate, officially, in the MOCA show, too, thus sucking up all the attention by their absence.]

UPDATE: Is there any discussion of earth art that cannot be improved by a little digging? [I am so sorry.]

After thanking me for the mention, Suzaan Boettger pointed out that in fact, she discovered Good Fuck, and Heizer’s work at Cornell, Depression, in the course of researching her 2002 book, Earthworks: Art and the Landscape of the Sixties [UC Press]. As soon as I saw the cover in my shopping cart, I recognized Boettger’s book, but I am pretty sure I had not read it, because I would have remembered this:

De Maria had arrived at the museum during the opening and, while visitors watched from behind the closed glass doors of the gallery assigned to him, raked the earth that student assistants had provided into a smooth shallow rectangle. He then used the tip of the rake handle to inscribe in capitals on a diagonal across this earthen rug’s surface the words GOOD FUCK. Considering the earth is traditionally coded female, this recalls the archaic practice by a male farmer of copulating with a virgin on a newly furrowed field to insure its fertility. [p.165]

Well. We will never see wall-to-wall carpet of Earth Room or the rows of poles piercing the Lightning Field the same way again, will we?

Boettger’s version also has the work on view for at least “a few days” before White Museum director Thomas Leavitt told the artist he would close the work off in advance of an elementary school group visit. De Maria and Heizer pulled out, so to speak, together.

There should probably be a limit on the number of curatorial WTFs in a single post, but the fact that neither artist nor their work were mentioned in the exhibition catalogue, and that Heizer’s participation in a related symposium was edited out of the published version of it, seems like pure institutional malpractice. Boettger found documentation of the works, her footnotes reveal, in a Cornell archive separate from the museum’s own exhibition archives. And Sharp’s account only came out years later. It really should not have taken until 2002 for information on these artists and their works to surface.

On the bright side, Heizer’s withdrawal of his work seems to have been a major pain in the ass for Cornell; the dirt excavated from his 8-ft deep, 75-ft long trench had been repurposed for other artists’ works, so it couldn’t be swept away so easily. But by then, all the critics and VIPs had been flown back to Manhattan on Cornell’s private plane. #junkets

“Draw a Straight Line and Follow It (Repeat): Walter De Maria’s Cricket Music and Ocean Music, 1964–1968 [aaa.si.edu, 2015]

This Land is Their Land [caa journal, 2013]