That is so Epic.

From Epic Brewing Company, Salt Lake City, Utah.

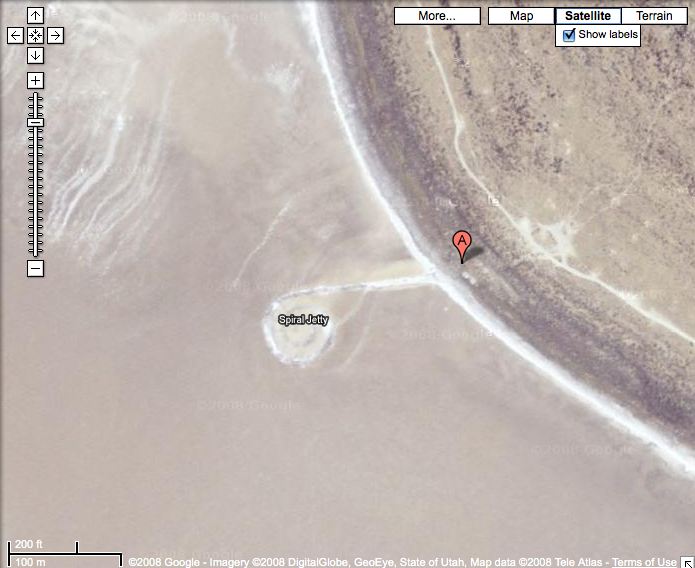

Spiral Jetty IPA | Epic Brewing Company [epicbrewing.com via the freshly relocated tyler green]

Related? The Shoppes at Rozel Point, from Visiting Artist (sic), a lecture involving Smithson which I gave at the University of Utah:

Category: spiral jetty

Hilton Kramer: TMI

God bless him, even if he’s on the wrong side of [most of the intervening 40 years of] contemporary art history, you gotta love Hilton Kramer’s eviscerating takedown of MoMA’s 1970 conceptualist exhibition, Information, curated by Kynaston McShine:

The exhibition is, in its way, amusing and amazing, but only because it upholds an attitude one had scarcely thought worth entertaining: an attitude toward the artistic process that is so over-weeningly intellectual that it is, in its feeble results, virtually mindless. Here all the detritus of modern printing and electronic communications media has been transformed by an international gaggle of demi-intellectuals into a low grade form of show business. It leaves one almost nostalgic for a good old-fashioned hand-made happening.

Though he only mentioned one artist by name in his NY Times review [Hans Haacke], Kramer did note the “great many blowups of junky photographic materials…of earthworks,” which I assume is a reference to the four Gianfranco Gorgoni photos that introduced the just-completed Spiral Jetty to the public.

Show at The Modern Raises Questions, July 2, 1970 [nyt archives]

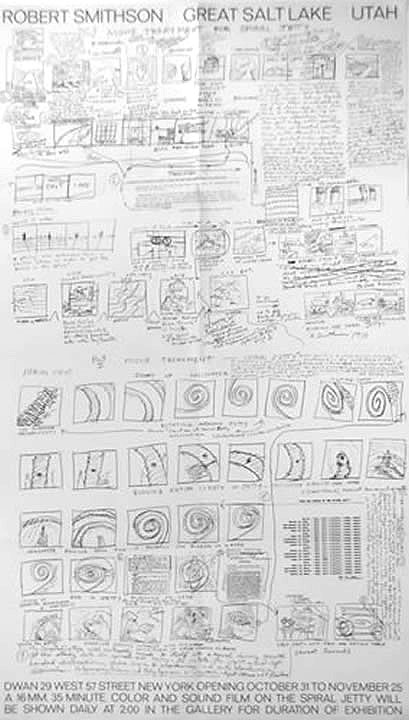

Wanted: Smithson’s Movie Treatment For Spiral Jetty Poster

I’ve been working on a shot-for-shot remake of the Spiral Jetty film for a while, and so I’m quite familiar with the storyboard-like drawings Smithson did for it. Familiar with them as drawings, that is. He called them Movie Treatments.

It’s a little embarrassing to admit I didn’t realize Smithson had used a treatment/storyboard for the flyer/poster of the 1970 Dwan Gallery exhibition of Spiral Jetty until I read it in Kathleen Merrill Campagnolo’s essay on the Jetty and its camera imagery in the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art Journal. But there it is:

DWAN 29 WEST 57 STREET NEW YORK OPENING OCTOBER 31 TO NOVEMBER 25

A 16 MM, 35 MINUTE COLOR AND SOUND FILM ON THE SPIRAL JETTY WILL

BE SHOWN DAILY AT 2:00 IN THE GALLERY FOR THE DURATION OF EXHIBITION.

The Dwan exhibition consisted primarily of Gianfranco Gorgoni’s large-format photos of the Jetty, eight of which were included in Kynaston McShine’s historic “Information” show at the Museum of Modern Art that summer.

Given the iconic aspects of the photos and the powerful influence of the film–not to mention the experience of visiting the Jetty itself–it’s somehow odd to think of encountering the Jetty first in terms of Smithson’s site/non-site paradigm, as a situation represented in a gallery.

It’s also interesting to note that the film only played once a day, not on a continuous loop as is often the case now. It was an event more than an installation.

Anyway, I would like you to send me one of these posters, please. If you have one you don’t need, or perhaps some extras. It need not be signed. Thank you.

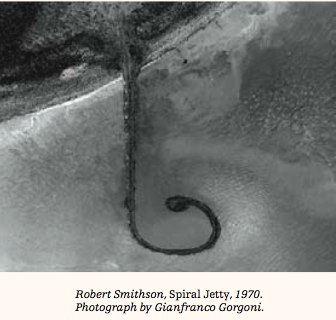

The Not So Spiral Jetty

For a generation of art watchers, Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty existed primarily as an image, via the making-of film and Gianfranco Gorgoni’s iconic aerial photographs, which were exhibited at MoMA’s seminal Information show and were published in Smithson’s Artforum essay on the work. This mediated encounter with the work inevitably affected its interpretation. But similarly, the 16 years of visibility and visitability since the Jetty’s re-emergence from the Great Salt Lake can lull you into a sense of complacency that you now know the work. And by you, of course, I mean me.

The latest issue of the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art Journal includes an excellent essay, “Spiral Jetty through the Camera’s Eye,” by doctoral candidate Kathleen Merrill Campagnolo, which looks at how Smithson used photography and film to shape not only the reception of the Jetty, but its conception and evolution as well.

For example, at first, and even until a week after it was supposedly completed, it wasn’t actually a spiral. The image above is from a contact sheet Gorgoni took in April 1970. It shows the Jetty:

…with a single, simple curve to the left, creating a hook shape with a large circle of rocks at the end…In a recently published account of the construction of the sculpture, the contractor Bob Phillips reveals that Smithson considered this first curved jetty, as seen in Gorgoni’s photographs, to be complete, but about a week after the construction crew had been sent away, he called them back to alter the configuration…

…Not surprisingly, the early version of the sculpture was not included in any of Smithson’s Spiral Jetty works. In fact, by the time he had finished his essay in 1970-71, the text reads as if the form the jetty took was a foregone conclusion from his first arrival at Rozel Point.

Campagnolo’s article has another Gorgoni photo, of Smithson and Richard Serra looking at a lost/destroyed sketch of Jetty v1.0 with v2.0 superimposed on it.

To see the sketch, you should really read the article. But I am reproducing the top half of the image here because I am in awe of Serra’s impressive Jewfro.

PDF: Vol 47: 1-2, The Archives of American Art Journal [aaa.si.edu via the Archives of American Art Blog Really? Yes. It’s awesome. [blog.aaa.si.edu, probably via tyler green, since it mentions hockey]

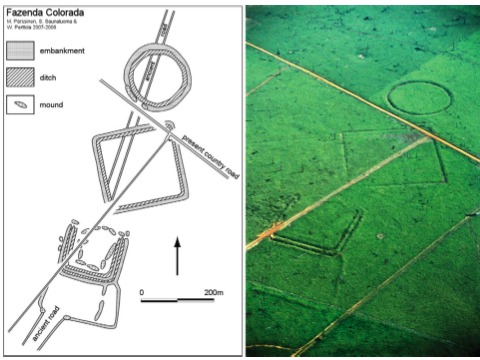

Everyone’s An Earth Artist: Lamanites

I guess if God can appear to a backwoods New York farmboy, send an angel to groom him for four years, and then command him to translate a sheaf of golden plates into the Book of Mormon, He can also guide Robert Smithson to build the Spiral Jetty in Utah; lure me out to visit it within a couple of months of its reappearance in 1994; and start me a-bloggin’ years ago about Earth Art and Google Maps; so that, when it’s on Discovery Channel, there’ll be someone to point out that the Pre-Columbian geometric earthworks in western Amazonia are–duh–Lamanite-era copies of Nephite-style forts.

But since that would require paying even a little attention or credence to the archaeology-based school of Book of Mormon apologists I’ll pass.

It’s enough for me to think of the headaches these earthworks will give to Michael Heizer.

‘Astonishing’ Ancient Amazon Civilization Discovery Detailed [discovery.com]

Pre-Columbian geometric earthworks in the upper Purús: a complex society in western Amazonia [antiquity.ac.uk]

Everyone’s An Earth Artist: Dolphins

I know dolphins are supposed to be super-intelligent and all, BUT. While this detournement of Smithson’s Spiral Jetty executed from rapidly dissipating, tail-agitated mud is passably performative, as a critique of entropy, it’s a little too pat and predictable. Back to the studio, dolphin!

Life: Bottlenose dolphins mud-ring feeding [youtube via, uhh..]

Convergence

If I’m a little high right now, it’s just because these conservators just hit like every art button I have:

To photo-document Spiral Jetty, we used a tethered helium balloon about 8-10 feet in diameter, attached to a digital camera that would take an image every few seconds until the camera’s memory card filled up. Each of us let out string from a spool and sent the balloon up anywhere from 50 to 600 meters, depending on what we were trying to capture and other factors such as wind and amount of helium to give lift. The results were absolutely amazing! Now I have a low tech, low cost way to take aerial images of the sculpture — something I plan to do on an annual basis. These images can be paired with data that we collected using a Total Station survey instrument in order to create scaled 3D maps and diagrams of the Jetty and its materials.

Extending the Conservation Framework: A Site-Specific Conservation Discussion with Francesca Esmay [art21.org via man]

For the Record, The Spiral Jetty First Re-Emerged In 1994.

Not 2004 when the state put up a sign pointing to it. Not 2002, when my sister first took a college date out to see it but Artforum’s Nico Israel couldn’t find it. 1994.

After a Salt Lake City artist friend, Patrick Barth, told me that Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty was partially visible in mid-summer 1994, I drove to the Jetty in my sister’s car–no way I’d take my own car–in early August 1994. The larger rocks were visible, forming a fragmentary outline of the structure. They were all covered in glistening salt crystals.

So please, enough with the, it re-emerged whenever the New York Times first found out about it nonsense.

On Dean On Ballard On Millar On Smithson

Who knew? Tacita Dean writes in the Guardian about her late friend JG Ballard’s shared interest in Robert Smithson:

My relationship to Ballard had begun a little earlier, with our mutual interest in the work of the US artist Robert Smithson. In 1997, I tried to find Smithson’s famous 1970 earthwork, Spiral Jetty, in the Great Salt Lake of Utah. I had directions faxed to me from the Utah Arts Council, which I supposed had been written by Smithson himself. I only knew what I was looking for from what I could remember of art school lectures: the iconic aerial photograph of the basalt spiral formation unfurling into a lake. In the end, I never found it; it was either submerged at the time, or I wasn’t looking in the right place. But the journey had a marked impact on me, and I made a sound work about my attempt to find it. Ballard must have read about it, because he sent me a short text he had written on Smithson, for an exhibition catalogue.

It was the writer, curator and artist Jeremy Millar who became convinced Smithson knew of Ballard’s short story, The Voices of Time, before building his jetty. All Smithson’s books had been listed after his death in a plane crash in 1973 – and The Voices of Time was among them. The story ends with the scientist Powers building a cement mandala or “gigantic cipher” in the dried-up bed of a salt lake in a place that feels, by description, to be on the very borders of civilisation: a cosmic clock counting down our human time. It is no surprise that it is a copy of The Voices of Time that lies beneath the hand of the sleeping man on the picnic rug in the opening scenes of Powers of Ten, Charles and Ray Eames’ classic 1977 film about the relative size of things in the universe.

As it happens, I’m reading Millar’s book about Fischli & Weiss right now. And Massimiliano Gioni and the Fondazione Nicola Trussardi are opening a nice retrospective of Dean’s work in Milan in a couple of weeks. As soon as my copy of Ballard’s just-published interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist arrives, the loop will be complete.

The cosmic clock with Ballard at its core [guardian, thanks stuart]

Visiting Artist [sic], Parts 7 & 7: Robert Smithson

These are the last two segments from the lecture I gave at the University of Utah School of Art in 2007, titled Visiting Artist [sic]. They’re both about Robert Smithson. The first [above] is about Smithson’s own 1972 slideshow lecture at the UofU, “Hotel Palenque,” which he also published as an Artforum article, and which his estate eventually sold to the Guggenheim as a multimedia installation piece of art.

I love “Hotel Palenque,” and took its irreverent challenge to the orthodoxy of art and art criticism as part of the inspiration for some of my own talk. In preparation for my own lecture, I tracked down some people who were present at Smithson’s original lecture, to see what the artist may have said or indicated at the time.

Unlike the Guggenheim, I am deeply unconvinced that the lecture is a work of art per se. But I find it useful asking how and why treat this thing [sic] an artist made/did/said differently depending on whether it is or isn’t Art.

The second clip is the hometown favorite, the Spiral Jetty. In 2007, the big questions surrounding the Jetty concerned its recognition as a tourist attraction. The state government decided to do a big cleanup of the industrial detritus and abandoned machinery on Rozel Point [they arbitrarily classified wood and stone structures as “historic,” while removing all metal.] And then Smithson’s widow Nancy Holt made offhand comments about how it’d be fine with Bob to rebuild the Jetty, because that wasn’t the kind of entropy he meant, anyway. So I riffed on what kind of entropy might be best for a once-obscure, once-abandoned, now-popular Earthwork.

All Visiting Artist [sic] posts:

Parts 2 & 3: On Dan Flavin

Parts 4 & 5: On Throwing Art Away

video of Part 6: On Joep van Lieshout, which I apparently didn’t post here

Parts 7 & 7 [sic] on Robert Smithson

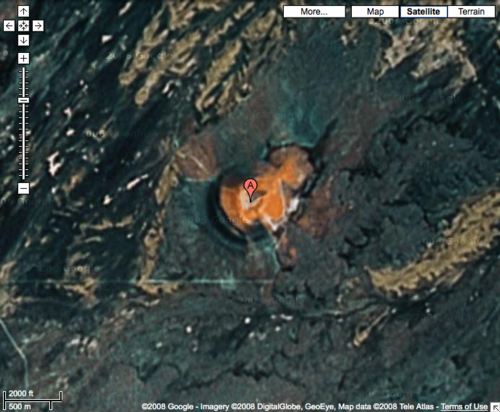

Finding Double Negative has never been easier

Not since we programmed it into the navigation system of my in-laws’ car, anyway.

The car also has an offroad navigation feature that logs virtual GPS breadcrumbs at preset intervals along the way, but it proved unnecessary. The nearly featureless mesa where Heizer’s land artwork is sited turns out to be a road with a name: Carp Elgin Rd.

In fact, there it is on Google Maps, one of the tightest satellite shots I’ve ever seen of Double Negative. Crazy.

Update: OK, not to get all George Bush and the Grocery Scanner about it, but I just typed “Spiral Jetty” into Google Maps, and it came right up. With an upgraded photograph–and a label.

In fact, here are complete driving directions to the Jetty from 213 Park Avenue South, the former location of Max’s Kansas City. [note: there is a weird little, unnecessary jog at the very end that I couldn’t fix, but I’m not worried. Given the rate at which technology is iterating and altering the way once-isolated land artworks are experienced and perceived, I expect a realtime Google Streetview of the Jetty is already being planned on a whiteboard somewhere in Mountain View.]

Clearly, Google has been augmenting its map search with information found on the rest of the web. An otherwise seemingly Googleproof project like Michael Heizer’s City, which he sited as remotely as he could, is pinpointed by latitude and longitude coordinates published on a Land Art site. City also has newer photos.

Roden Crater’s there, under “Roden Crater, AZ,” but it still has the quaint, old-timey satellite photo from 2005 or whatever. I hope they’ll get around to upgrading it by the time Turrell finishes.

Backroads Backstory: Walter De Maria On Michael Heizer

I started poking around a bit on the making of story of Michael Heizer’s Double Negative. I’d known that it was commissioned by Virginia Dwan, the incredible gallerist who was also behind Smithson’s Spiral Jetty. Here’s a bit of her story from Michael Kimmelman’s 2003 visit with her:

She contracted him to do a work. He disappeared. Months later it was done. ”Double Negative” is a 1,500-foot-long, 50-foot-deep, 30-foot-wide gash cut into facing slopes of an obscure mesa in Nevada, a project that required blasting 240,000 tons of rock. ”It cost under $30,000,” Ms. Dwan says, ”pocket change for art today. I saw it only after it was finished. That’s how I operated. If I believed in the artist I trusted him.”

Then I came across an interesting 1972 Smithsonian interview Paul Cummings with Heizer’s earthwork colleague, Walter De Maria, two artists who romanced the desert together. I love the unselfconscious references to Kerouacking and creating an art movement. No way you could pull that off today:

WDM: Well, I drove across the country with Mike Heiser who I had been spending a lot of time with in ’67. So we had this chance to have the great American Kerouac experience of driving, you know, drive, drive and it never stops and four or five days later you can make it if you drive night and day. When I had first driven the country in the summer of ’63 from New York back to California, it was the most terrific experience of my life, experiencing the great plains and the Rockies, but especially the desert, you know. No, I would say the drive through Nevada in ’63 was the first time I was in the desert. And that memory was to come back in the crisis. Where is the best place in the world? It’s what I saw in Nevada. So it was a chance to go back to the desert for a second time and this time to start going out there often. We met flyers and we learned what it was like to fly small planes and drive trucks on these dry lakes and stuff.

…

We had a lot in common; we knew the whole situation so that gave us something to talk about and from that point it became interesting that he would change from shaped canvas painting to sculpture, and I was at the point of changing from steel sculpture into the land sculpture. So it was a move that we both wanted to make at the same time. We have both been developing the land sculpture simultaneously since that time, five years ago, just about until today. We’re really starting the sixth year. I mean, you know, we did it. It’s something that two people could do that one couldn’t, really, create a movement, because if one person does it, it is almost an eccentricity, but if two people are doing it and then they influence two others or three. It takes no more than three or four or five people to make a movement and then those people of course can have a hundred or two hundred or five hundred or a thousand following them. But the key idea is to develop two or three people. But it’s not necessary, sometimes three or four or five people could be working simultaneously. Like this guy Richard Long was working in England, walking around in the fields in ’68 also. That was completely independent simultaneous development…

The mention of flyers and deserts reminds me of Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point, which I’ve been watching lately. James Turrell is another flyer–and land art biggie, what with the Roden Crater and all. Don’t think I’ve heard much mention of that. Of course, there was Smithson and The Plane, but that wouldn’t be till ’73. Anyway, here’s more De Maria on one paradox of land art:

We’ve fought a lot of the same people; we’ve shared some of the same patrons, the same gallery like Dwan, Frederich for a while in Germany. Now he has another gallery. And all of our same problems remain, like to make earth art exist in the face of a lot of the same structural problems that still exist. Galleries are not set up to back major sculptures.

PC: Right.

WDM: There’s nothing set up to sell major sculptures. Museums do not commission major sculptures, even though they go off and spend five million dollars on an old painting. And not only that, a lot of people don’t believe that it really exists. There is still a lot of misconception that it exists only for the photograph and not for itself. It’s so far away that maybe everyone in the art world knows about our sculpture but not even one thousandth of one percent of a person has ever seen one of the pieces with is a very interesting conceptual and visible aspect of something that is massive. So, with all of these confusions and contradictions still inherent in the work, one could see another five years of good problems and hopefully some good solutions coming up. [emphasis added]

And it turns out that De Maria created his own trench-in-the-desert land art in 1969, Las Vegas Piece, which is just up the road from Double Negative. Or should I say “road.” CLUI says it’s located on Carp/Elgin Road, which, according to my father-in-law’s GPS navigation, is the same dirt road that passes alongside Double Negative.

De Maria talked about Las Vegas Piece in the Smithsonian interview. But when he reports Dwan’s account of visiting it, it is Kimmelman who waxes a little romantic:

It consisted of dirt paths he cut into the Nevada desert, going nowhere. In my mind — maybe Walter would say this is untrue — the desert setting, the heat and sun and emptiness were so important to the work because you were made to feel absolutely alone. First, it was a safari to find it, and when you did, you were separated from everyone else if you wandered down the paths, because the land was uneven, although it looked flat from far away, so you would find yourself on the far side of a rise, alone in the desert.

”I love the sense of isolation and solitude. But at the same time Walter’s art almost pushes a spectator away, as if he’s saying, ‘Stay back.’ ”

And so it goes that the foreboding environment of the desert itself moves to the foreground of the land art experience. It’s part of the mythology and story of the piece, told and retold without firsthand confirmation by the 99.999% of art world citizens who don’t actually go. Like this NY Times travel article starring Dave Hickey and his wife as daring land art tour guides:

Mr. Hickey’s wife, the curator Libby Lumpkin, had suggested that Chris and I drive into the desert to see Michael Heizer’s earth art piece from 1969-70, “Double Negative” (doublenegative.tarasen.net). A work I was curious to see, it was famously hard to find. She had us meet her at the Las Vegas Art Museum, where she is the consulting executive director, to get directions.

…

She warned us to take plenty of water. People had died, she claimed, after losing their way on Mormon Mesa, where “Double Negative” is carved. The Internet directions she’d handed us turned out to be more precise on paper than in the featureless landscape. After driving an hour and a half northeast to Overton, we followed a dirt road up the side of the mesa.

Rocks on top threatened to puncture the oil pan on the Neon, so I parked. We stumbled around, visoring our hands against the sun. Nothing in sight looked like art.

We flagged down two cars but no one had ever heard of the work. Discouraged and clueless, we were heading back to the city when we saw an S.U.V. The driver, an elderly man from Overton, had been to “Double Negative.” He pronounced it a “tax dodge,” but agreed to lead us there anyway.

Now I want to go back and see what’s up with De Maria’s Las Vegas Piece, but not only is CLUI’s coordinate map hopelessly vague [“The site is 37 miles down the road, off another small trail.”], not even they can be bothered to confirm its continued existence. All they say about it is, “Apparently, no longer visible.”

So How’s That Spiral Jetty Doin’?

Is he done? I think so. Tyler Green has turned Modern Art Notes into State of Spiral Jetty Notes this week, and it seems clear to me that the biggest entropic threat Smithson’s masterpiece faces is not natural, but institutional.

Green looks at the mining and commercial interests with development plans for the Great Salt Lake; Utah state government officials who court industry and economic development and who are only beginning to grasp the Jetty’s global significance; local conservation and environmental groups whose shoestring grassroots efforts were the only thing that stopped the oil drilling near the Jetty this past spring; and last and unfortunately least, Dia, the art institution which is steward–and in many cases, commissioner–of many Jetty-vintage earthworks.

I wonder if it means anything that Smithson’s widow and estate representative, Nancy Holt, isn’t really discussed or quoted in the otherwise exhaustive series? Or that there’s no mention of Dia’s total ball-dropping in regard to the state’s apparently unilateral decision in 2006 to “clean up” the shore line near the Jetty, a process which involved removing several dozen truckloads of “junk,” including some industrial ruins that Smithson referenced in his siting of the piece.

Dia’s lack of involvement and strategic vision for the Jetty is complicated at the moment by the institution’s own turmoil and leadership transition, but I can’t help but feel worried even calling Dia an “institution.” Even under Michael Govan’s high profile leadership, Dia has always felt like a virtual organization, an instantiation of the whims of whatever deep-pocketed funder was around at the moment. [Wow, was MIchael Kimmelman’s look at Dia’s manic history really from 2003? It feels much longer ago than that.] The kinds of political and coalition-related imperatives that Tyler discusses–and on which the Jetty’s very survival apparently now hangs–seem completely alien to a bauble like Dia.

MAN Series on Preserving Spiral Jetty [modern art notes]

Previously: Oil drilling was part of the picture when Smithson sited the Jetty

Cleanup crew: 1, Entropy: 0

Related rumination: What if sprawl is the real entropy?

Well, I Remember The First Time I Visited The Spiral Jetty

Former NGA curator and Dia director Jeffrey Weiss writes about the state of Land Art in the latest issue of Artforum. His focus: T.S.O.Y.W., a 3-hour Earthworks road trip movie/installation by Amy Granat and Drew Heitzler shown in this year’s Whitney Biennial, and the Sculpture Center’s recent exhibition of feminism and Land Art in the 1970’s [which featured the Agnes Denes work, Wheatfield – A Confrontation in Battery Park City that I mentioned a couple of months ago.]

As Earthworks come of age, their fate has begun to look contingent and fragile. Those who are charged with caring for the sites are rightly doing what they can to forestall change; but a true poetics of Land art–given the very nature of the medium–must at least contend with the conflict between an ethic of preservation and the entropic pull of nature and culture that belongs to the content of the work. In this setting, Granat and Heitzler are melancholic visionaries. Their wheels, like reels, turn in order to draw a straight line and follow it: Their line is the road, a figure for unbounded space and inexhaustible time. But as their bike moves forward, their eyes gaze, historically, back; T.S.O.Y.W. shows us that memory has become a chief element of the temporal condition of the Earthwork. The film’s end is a running-down and out, a sudden shift from images of the infinite desert to scarred film leader, then, abruptly, to nothing at all. Forever turns out to be the ultimate conceit. [emphasis added]

Hmm, let’s ignore the conceit of a film ending abruptly while it’s actually screening on an endless loop in a gallery.

I’m intrigued by the idea that memory is a “chief element” of Land Art and its “temporal condition,” if it somehow equates to the divergence between the contemporary condition and experience of visiting the work/site and its various representations, whether in film, photograph, or documenting ephemera.

For most art audience members over the intervening decades–curators, critics, collectors and artists included– Land Art exists as books, photos, gallery presentations, and texts. At the Whitney’s Robert Smithson retrospective in 2005, one symposium panelist went so far as to argue that Spiral Jetty was primarily a film and photo work, as if the jetty itself were just a location, a bit of IMDb trivia. It sounded to me then like just the kind of critical reading that a New York art worlder would make who’d come of age when the Jetty was submerged, and who’d never bothered going to Utah in the 10+ years since it re-appeared.

With images and expectations formed in our head, actually visiting an Earthwork can be as disorienting as meeting your favorite NPR host. Or if, as Weiss points out, the work has deteriorated over time, it’s like meeting an author who hasn’t updated his bookjacket photo for a while. And the disconnect can be jarring; When Titus O’Brien made his pilgrimage to Smithson’s last work, Amarillo Ramp, he found the powerful sculptural form of the iconic 1973 photograph had become “a worn down, weed covered, neglected berm of dirt you’d just mistake for an old watering trough dam. A phantom.”

But memory is more than the gap between reality and what we think reality is; it’s the reconciliation and construction of the two. Weiss’s concerns about the complications Land Art curators face is right, but maybe not in the way he says. From Marfa to the Lightning Field to the Jetty to even Michael Heizer’s Double Negative and Turrell’s Roden Crater, the Earthworks Road Trip has matured in the last decade as both a real experience and a concept. As more people make the pilgrimages and have personal encounters with these works, not only do their memories of the works change, but other people begin to perceive the works not just as images in a book or on a wall, but as visitable sites.

I wonder how the perceptions and understanding of Walter deMaria’s Lightning Field change when they’re based, not just on John Cliett’s dramatic, official photos [via], but on firsthand accounts of the 24-hour visiting experience, very few of which appear to involve actual lightning? And how would that change if Dia and deMaria allowed visitor photographs? When it comes to Land Art in the present and future, there are still a few more conceits left to be addressed.

Is The Spiral Jetty Visible? Check USGS Elevation Data

So the geocachers I’ve relied on to provide the link to the USGS real time data about the elevation of the Great Salt Lake have rejiggered their site.

So here’s the link I’m using to see if the Spiral Jetty is visible, submerged, or high and dry.

The Jetty’s elevation is 4,197 feet above sea level, so with the lake level at 4,194, I suspect it’ll be high and dry tomorrow.

update: it was, and it’s spectacular, black-on-white, with the shimmering water just off the outer edge of the spiral. Also, we got a flat, which I had to change at the Jetty, which sucked. The flat, of course, not the Jetty.

USGS Water Surface Elevation, Great Salt Lake near Saline, UT [waterdata.usgs.gov]

Previously: lots of Jetty goodness on the greg.org