Last November writer and curator Hilton Als delivered two lectures at the Menil Collection about his research into its founder Dominique de Menil. They’re predictably unexpected, wonderful, and important.

Category: inspiration

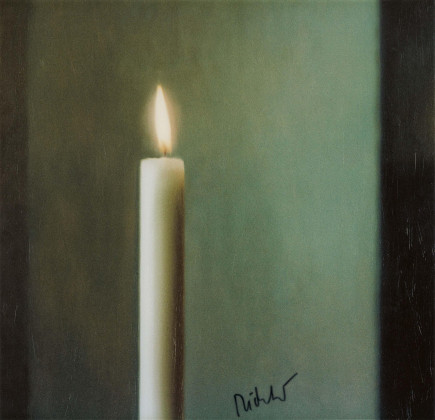

For Sale: Richter Non-Edition, Signed

What is this? The Cologne auction house Van Ham says it is a Gerhard Richter. Kerze is an offset print on aludibond and face-mounted with diasec, so it is produced like a Facsimile Object. But it is signed on the front. There is no CR information, or even a date, but it is described as a benefit edition created for fiftyfifty in Dusseldorf. I vaguely remember that. Sure enough, in 2012, Richter donated 36 signed works to raise EUR300,000 for the homeless support organisation, including both this candle picture and Betty, his iconic portrait of his daughter.

None of these objects appear on the artist’s website, however, and the online gallery is long gone. Except for one snapshot in the Internet Archive. The list includes half a dozen signed posters, and one page from a catalogue, all face-mounted on UV diasec; a leftover signed print from 20,280, a newspaper edition Richter made in the Rheinische Post in 2010; and 5 or 10 copies each of six “Offset Edition (2011) from Tate Modern,” including Kerze, but also Betty, 4.096 Colours, and 100x100cm prints of two of the Cage paintings (4 & 5) that are the stars of Tate’s Richter offering. They sound like gift shop souvenirs, but signed.

Of course, that distinction is not so clear cut. Richter made a full-size giclée grid edition of Cage 1, which was also for sale at the Tate’s shop during his 2011 retrospective, Panorama. This all feels like the genesis of Richter’s Facsimile Object project, the experimental soup of form, editioning, signing, and auratic status–and from the artist’s perspective, at least, these fiftyfifty pieces are on the other, autographed side of the work/non-work line. And yet the quasi-canonization of the facsimile objects, and their proliferation in the market, help to make that line less relevant with every passing year.

1 Dec. 2021, Lot 387 | Kerze, Gerhard Richter, est. EUR12-18,000 [van-ham.com]

Previously, related: For Sale: Richter Edition, Never Signed

I shall call him Heni-Me

Soft-Core: On Additional Material and Non-Work

[THERE’S AN UPDATE: READ ON, THINGS ARE BETTER THAN I WOUND MYSELF UP TO THINKING.]

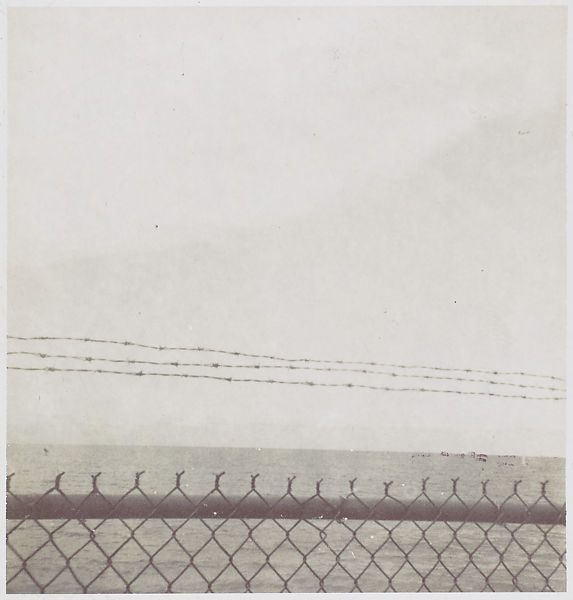

The earliest work by Felix Gonzalez-Torres in the Metropolitan Museum’s collection is also the smallest. It is untitled, an instant black & white photo of the sea through a Cuban fence. It’s about 2.75 inches square. It is signed and dated 1985, and has a fragment of a magazine collaged on the back that reads, “THE BO–/ ANYMORE.” By the time it was acquired at the end of 1996, the year of the artist’s death, the Met had already acquired two similar sets of photos by Gonzalez-Torres: photogravures of sand, and cloudscapes. Similar, but different: this one is not an artwork. “Although made, signed, and dated by the photographer,” the catalogue entry reads, “Gonzalez-Torres thought of works such as this [photo] as lying outside his core oeuvre.”

Published in 1997, just in time to record the Met’s acquisition, the Felix Gonzalez-Torres Catalogue Raisonée has three categories: Works, Additional Material, and Registered Non-Works. The photo above is in the second category. When the CR was released, Gonzalez-Torres was the most important artist in the world to me, and I wanted more of his works, not fewer. I was upset for these somehow downgraded works, and for the sleights they faced in the discourse, the gallery, the market. I couldn’t accept that the same artist who’d shown me that the most remarkable things could be art–a pile of candy, a stack of paper, a jigsaw puzzle, a pair of clocks–also said they couldn’t be.

My incredulity over Felix’s work fueled a years-long contest with the declarative process, what artists called objects, what they kept, what they destroyed. It helped me keep an eye out for these marginalized–and invisible, since there weren’t even any pictures–works. But even as I developed more nuanced appreciations of [other] artists’ agency, these non-art designations still gnawed at me. Until the other night, when I started writing this. It’s been almost 25 years: what’s going on?

Continue reading “Soft-Core: On Additional Material and Non-Work”A Walking Stick Frederick Douglass Gave To John Brown Would Be Quite A Find

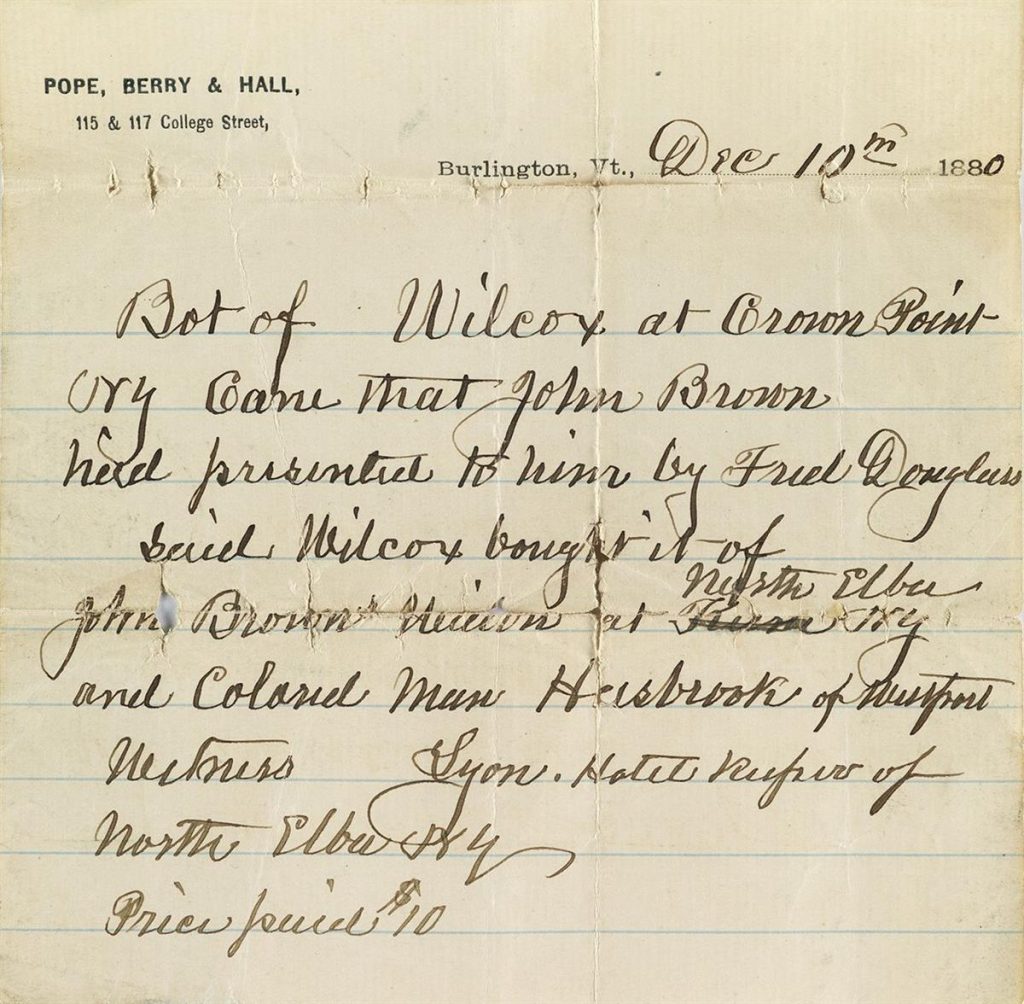

This walking stick carved with three alligators is being sold at Swann’s upcoming African Americana auction, along with a note stating that the cane was a gift from Frederick Douglass to John Brown, and tracing the provenance of the cane from Brown’s widow to the purchaser. After noting the well-documented history of Brown and Douglass’s interactions, Swann continues:

We have found no contemporary documentation that Frederick Douglass ever gave John Brown a cane or walking stick. Nor does the cane itself bear any inscriptions.

The entire burden of proof rests on a slip of notebook paper passed along with the cane for the past 140 years, on the letterhead of Pope, Berry & Hall of Burlington, VT, 10 December 1880: “Bot of Wilcox at Crown Point, NY, cane that John Brown had presented to him by Fred Douglass. Said Wilcox bought it of John Brown’s widow at North Elba, NY and colored man Hasbrook of Westport. Witness, Lyon, hotel keeper of North Elba, NY. Price paid $10.”

This story seems plausible. The gift from Frederick Douglass to John Brown would have likely been in the late 1850s. After Brown’s execution in 1859, the cane would have been left to his widow Mary Ann Day Brown (1817-1884) at her home in North Elba, NY. Probably shortly before she sold the North Elba property in 1863, it would have been given to Josiah Hasbrouck (circa 1818-1915), an African-American farmer who was a close friend and neighbor of the Brown family. Hasbrouck resided in Westport, NY from 1871 until before 1880 when he moved to Vermont. During this period he would have sold it to a man named Wilcox from Crown Point, NY; the only Wilcox there in the 1880 census was a 27-year-old laborer named John Wilcox. On 10 December 1880, it was sold by Wilcox to George F. Pope. It has been consigned by a Pope descendant.

It only gets better from here:

Any link in this chain could have been invented or exaggerated by any actor up through 1880. John Brown might have told his wife the cane was from Douglass, but it really wasn’t. Mary Brown might have told her friend Hasbrouck that it was John Brown’s cane, but it really wasn’t. Hasbrouck might have invented a Brown family provenance to effect a sale to Wilcox. Wilcox might have invented the whole story to effect a sale to Pope, although it seems unlikely he would have gotten so many details right. Less likely, George Pope could have invented the whole story and drew up this note to support it; or the original cane could have been swapped out at some point in the intervening century to pair with the note.

On the other hand, we have found no way to disprove the story, either. We are confident that the note is dated 1880, and we have found no reason to doubt the credibility of any of the parties. If this really was a gift from Frederick Douglass to John Brown, well, that would be quite a find.

Myself, I am glad to have found this auction, the contemplation of which, along with the contingencies and uncertainties of history, provides great pleasure. I haven’t had this much fun thinking about the way objects accrue an aura of significance since the slivers of Washington’s coffin and the random, stranded andiron with the attribution to Paul Revere.

07 May 2020, Lot 65: (SLAVERY AND ABOLITION.) Cane said to have been a gift from Frederick Douglass to John Brown. est. $4,000–6,000 [update: it sold for $5,720.] [swanngalleries.com]

Related? Mary Todd Lincoln gave her late husband’s favorite walking stick, TO Douglass, and another walking stick given to Douglass just sold for $37,500 in February and went to the South Carolina State Museum this week. OK, now something’s up. The Frederick Douglass Historic Site run by the National Park Service has a cane with an engraved silver band that reads, “FREDERICK DOUGLASS/ 1882/ FROM HOUSE MADE BY JOHN BROWN”.

Also, not related, unless? Preston Brooks, a pro-slavery congressman from South Carolina beat the crap out of Charles Sumner, an abolitionist senator from Massachusetts, with his cane, on the floor of the US Senate on May 22, 1856.

Wouldn’t You Like To Be A Tania, Too? [UPDATED]

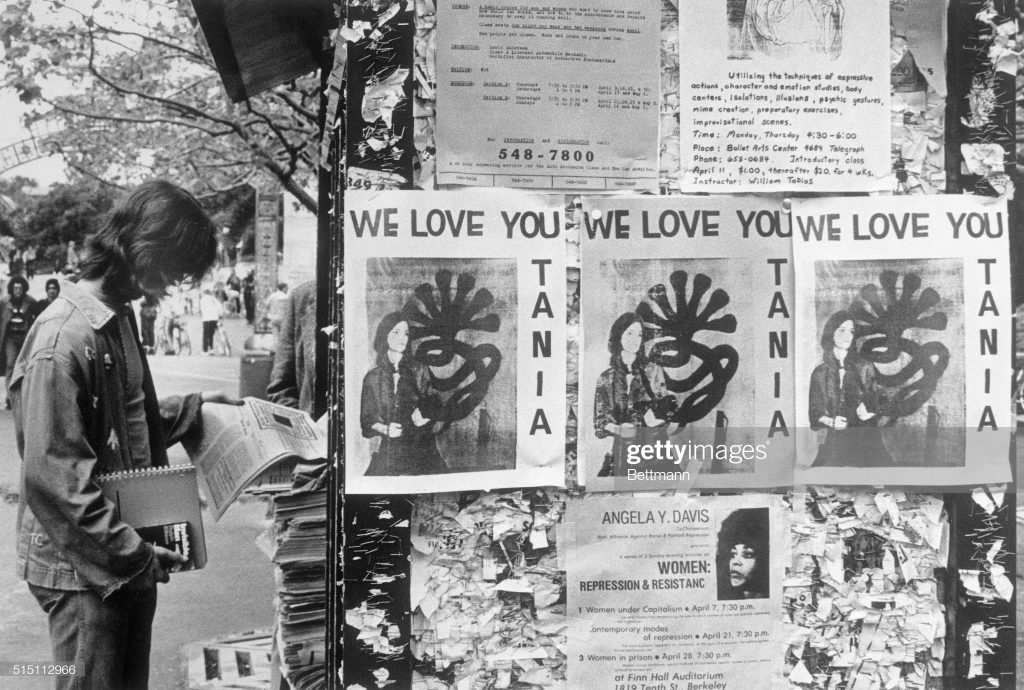

You know what I have never seen? An original “WE LOVE YOU TANIA” poster. Which might be easier to explain than you might think. If my own vintage photo captions are to be trusted, the photo of Patricia Hearst reborn as Tania of the Symbionese Liberation Army was only released on Wednesday, April 3, 1974, less than two months after her kidnapping. It accompanied a tape recorded statement by Tania, which was delivered to the offices of leading San Francisco counterculture/rock radio station KSAN, Jive 95. The photo ran on the front page of newspapers across the country on April 4th. [If I recall his Guggenheim clippings collection correctly, On Kawara read about it in the Washington Post.]

Getty’s original caption for the above image says, “Posters reading ‘We Love You Tania’ appear on bulletin boards at the University of California campus 4/15,” the day “she was identified by the FBI 4/15 as one of four armed women who took part in the robbery” of the Hibernia bank across the bay in San Francisco.

But the posters above and below Tania show events on April 11 and 7, respectively. So it seems more likely to me that Hearst’s Berkeley classmates posted their flyers–and they were photographed–soon after the Tania image was released, not, as it sounds, in celebration of the hours-old bank robbery. So this is a very narrow window in which to celebrate Tania’s revolutionary activities without celebrating her crimes. Or without at least using the security camera still of her from inside the bank.

(Original Caption) Someone waiting in line to watch the Patricia Hearst trial 2/23 brought in a huge drawing depicting Patricia Hearst holding a weapon copied from a photo taken at the University of California at Santa Cruz, uses her head in the drawing for a photo.

Is it possible for a photo archive to be even less helpful in its archiving? The only thing Getty managed to record about this photo of an extraordinary life-sized cutout painting (not a drawing) on board of the Tania portrait is the date (February 23, 1976).

I can find no source for the claim that the Tania photo was taken at UCSC, and a great deal of documentation that the SLA didn’t get farther than Daly City before the Tania photo was released. And though it is unspecified, this installation photo must have been taken outside the Federal Courthouse in San Francisco. Was it the painting itself, perhaps, that came from Santa Cruz? [update from a new source: it was apparently the young woman in the cutout who was from UC Santa Cruz: one Jean Finley. It also says the drawing (sic) was brought by “someone,” and that the Tania photo comes from the Hibernia Bank robbery. Boomers made news hard.]

The photographer, and more importantly, the artist who made the cutout painting, and most importantly, the current status and location of the cutout painting at this moment, are all unknown. If you are the boatshoed man on the right, or know him–he would be in his mid-60s now–please do get in touch. There are works in progress.

UPDATE: The internet is not canceled yet.

Within hours of posting this, Bean Gilsdorf tweeted that perhaps this woman posing in the Tania painting was Jeanne C. Finley, the artist, filmmaker, and California College of the Arts professor who had attended UC Santa Cruz. A couple of quick, shocked, and bemused emails later, we knew. That is her, and the artist who painted that thing is Alison Ulman. Here I quote Finley:

[T]he fact of that image is that it is an incredible artwork by my very best friend from childhood, Alison Ulman, that she did when we were in college at UC Santa Cruz back in the truly experimental days of that institution. Alison was obsessed with Patty Hearst and we both attended the trial. She created that work as a public artwork (long before the idea of social engagement ever was a thing) that the public would engage in while they waited in line to get into the trial. On one side was Tanya with the 7-headed cobra, on the other side was Tanya as a debutante. Everyone wanted to have their photograph done on the 7-headed cobra side! We had to get in line at about 1am and sleep on the sidewalk until dawn because there was so much public interest in attending the trial and it was a great way to pass the time.If you try to google Alison all you’ll find is this 15-year-old website. (http://endlessprocess.com/) …She is an amazing artist, and lives a most unconventional life…not one that really intersects anymore with the art world, but that is really the art world’s loss. We’ve been best friends since 2nd grade where we lived two blocks from one another and spent every day together as kids. We decided we wanted to go to college together so we both applied to UC Santa Cruz because we read that there was co-ed nude sunbathing on the dorm roofs. Santa Cruz was really hard to get into then, so the other artists in art school with us were all pretty amazing people. I felt so lucky to be there and have the freedom to be an artist and do things like this with my best friend.

On Shaker Gift Drawings

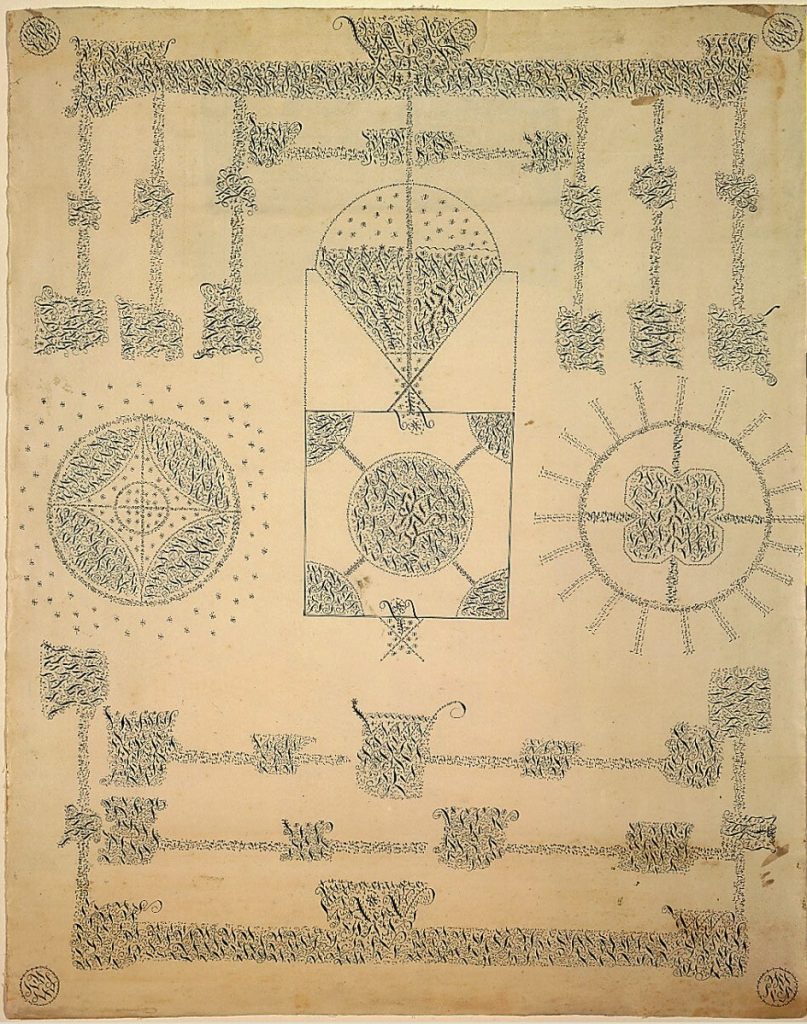

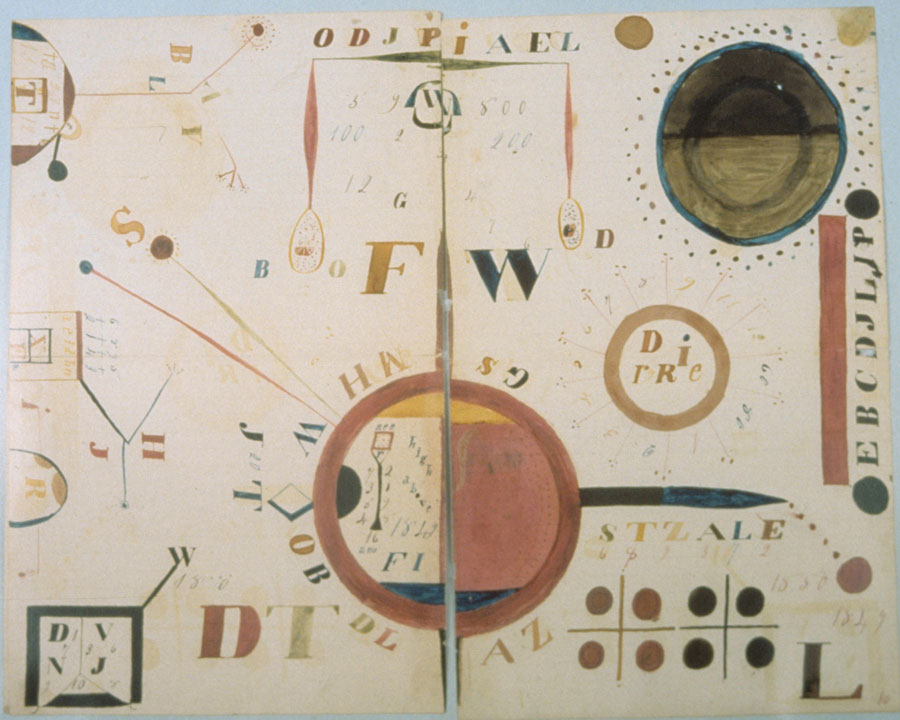

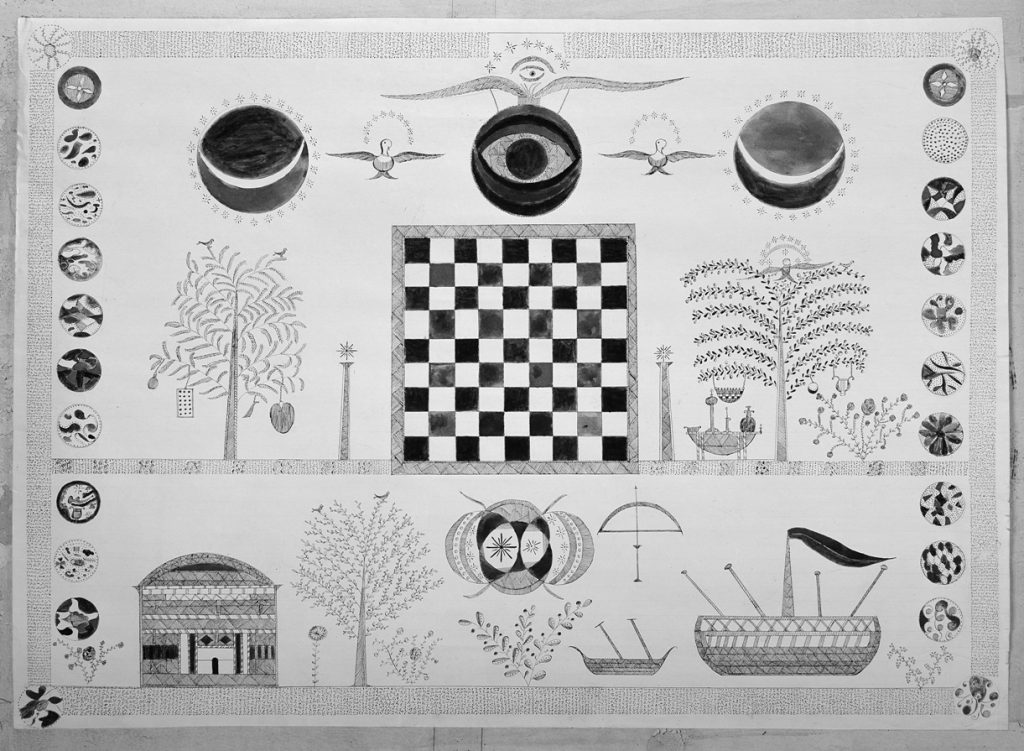

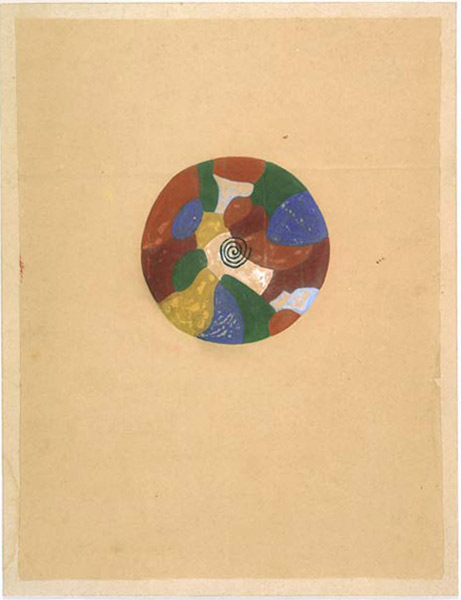

I can only be grateful to Léonie Guyer for writing about her transformative encounter with Shaker gift drawings, even though she’s been sleeping on this info for twenty two years.

It’s not her fault The Drawing Center held its exhibition of Shaker gift drawings and gift songs in November 2011–wasn’t everyone downtown a bit preoccupied?

And there are enough conflicting, self-serving accounts of its creation that it’s understandable, I guess, if it’s not yet universally recognized graphic design history that the CBS logo came from a detail of a Shaker gift drawing, an all-seeing eye spotted in 1950 by William Golden in Alexey Brodovich’s magazine.

Shaker furniture, via Sheeler, was my bridge from American antiques to modernism. I practice a religion founded in the same mid-19th century hothouse of spiritualism that had Shaker “instruments” seeing visions and dreams and visitations and translating them to “makers,” who drew them on paper. I made my Father Couturier pilgrimages early at Dominique de Menil’s urging at the Rothko Chapel. I swooned over Hudson’s tantric paintings [which were meditative objects, not products, but still]. I MEAN, HILMA AF KLINT, PEOPLE.

And I still can’t help feel that the world has somehow conspired to keep me from ever hearing about Shaker gift drawings. And I am shook.

In The Place Just RIght [openspace.sfmoma.org]

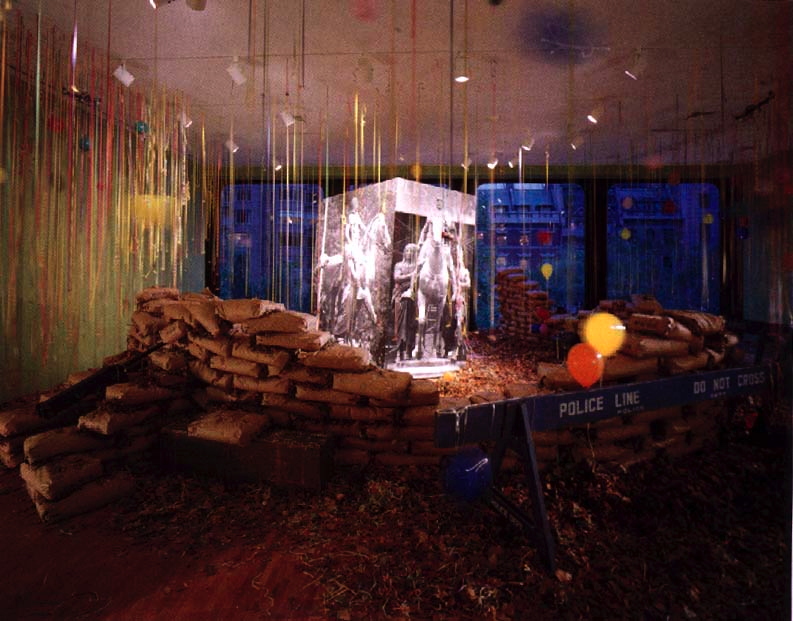

Public Enemy Nos. 2–?

I’ve written about “Dislocations” before. It’s one of the contemporary shows at MoMA that left a deep impression on me when I first moved to New York. It was in 1991-2 when Rob Storr curated huge, room-dominating sculptures by Chris Burden and Louise Bourgeois, and installations [!?] by Bruce Nauman, Adrian Piper, the Kabakovs, and David Hammons.

I just found this 5yo photo of Hammons’ Public Enemy, which I guess I had looked up because I was deep into photomurals at the time, and really wanted to find (or make) Hammons’ big photocube of the piece’s namesake, Teddy Roosevelt and his Grateful Savages [sic, obv].

In the intervening years MoMA has upped their archival game significantly, by putting a ton of exhibition material online, including the press release, checklist, brochure, installation photos, and a pdf of Storr’s catalogue. [Oh wow, Sophie Calle was in that show? Guess her intervention–removing paintings from the Modern’s galleries–was so subtle, I forgot.]

This was the first work of Hammons’ I’d ever seen, probably the first time I’d heard of him. Which seems crazy now, but reading the show’s time capsule of a catalogue, maybe I wasn’t so far behind. Storr waxes and marvels at what is now known about Hammons’ practice:

Hammons has preferred the city as a workplace and its citizens as his audience and sometime co-workers. Street flotsam and jetsam are his materials. What he brings to the gallery is all and sundry that it traditionally excludes. What he extracts from those materials and brings to the objects and installations that he has created outside the museums are the marvels and mysteries that lie already and everywhere to hand along heavily trafficked thoroughfares, in public parks, and in the so-called vacant lots littered with the evidence of their constant nomadic occupation and use…

“I like doing stuff better on the street, because art becomes just one of the objects that’s in the path of your everyday existence. It’s what you move through, and it doesn’t have superiority over anything else.” [he said in an otherwise unpublished interview which I now think we should unearth. -ed.]

Storr goes on about Hammons’ improvisatory process, “like jazz,” in which, despite a year of lead time, “all options remained open and the result wholly unforeseen” until the artist arrived to install the work. Which must have given MoMA an institutional heart attack.

And which, really? Because you can’t just pick up four huge photomurals or a substrate for them. And those sandbags seem very manufactured and ordered from somewhere. True, if you just work fast enough, those NYPD barriers were all over town, free for the taking. [Do they still have those? For throwback protests?]

What I thought about yesterday was whether Public Enemy still existed, or could be recreated. What I wonder about today, though, is what it’ll take for Uncle Teddy to get the Silent Sam treatment.

Public Enemy was installed in “Dislocations” at The Museum of Modern Art from Oct. 1991 through Jan. 1992 [moma.org]

Previously, related: Chris Burden’s Other Vietnam Memorial was in “Dislocations”, too

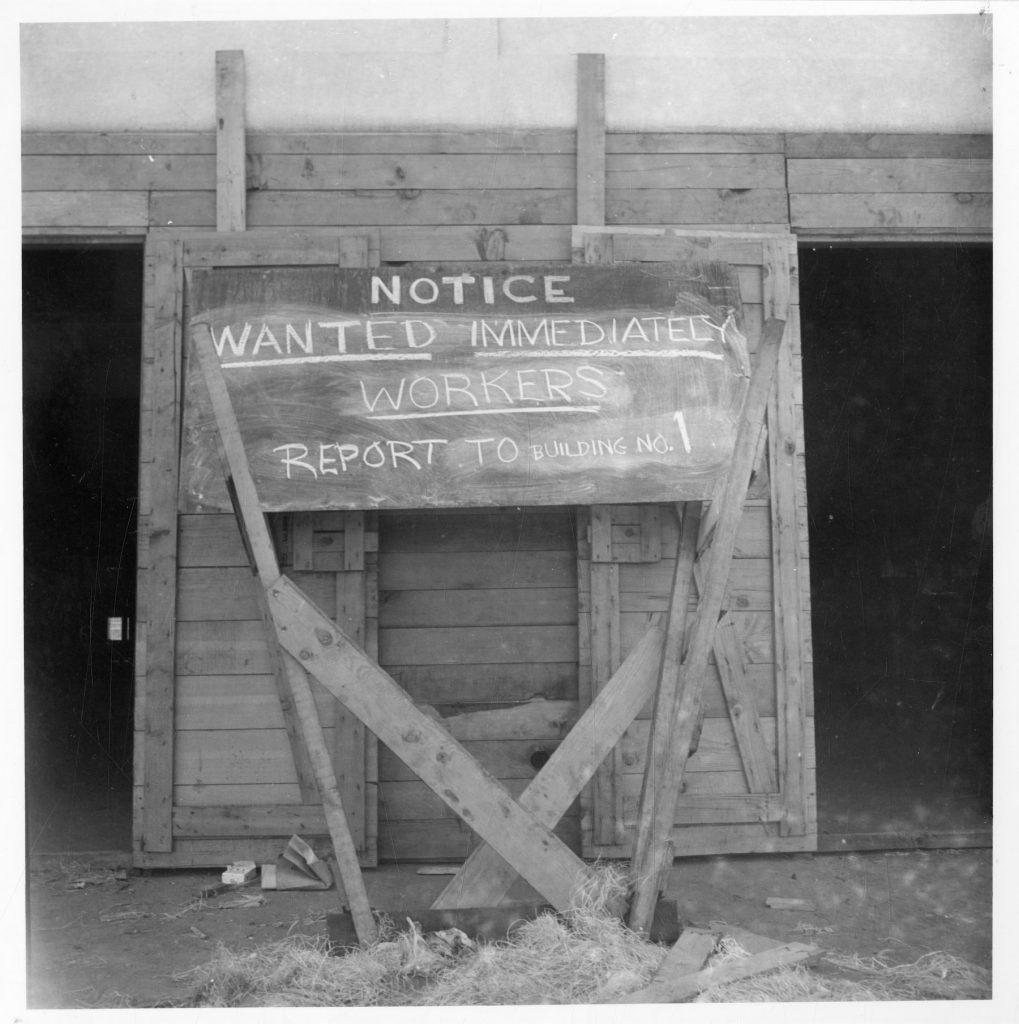

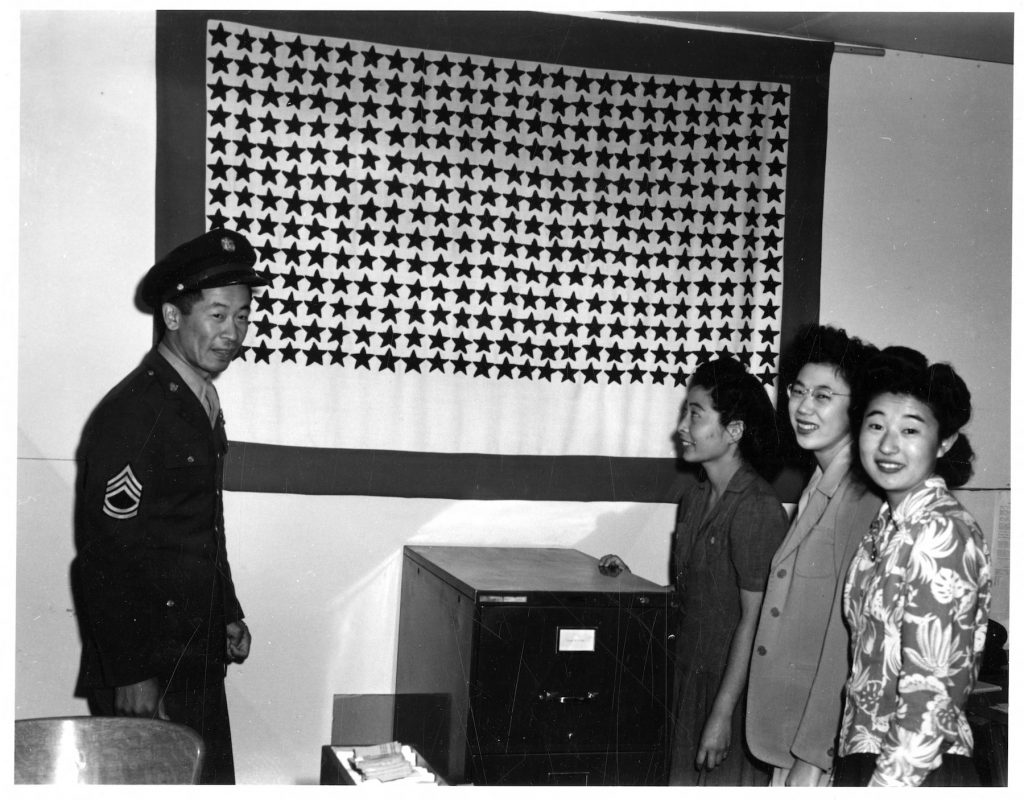

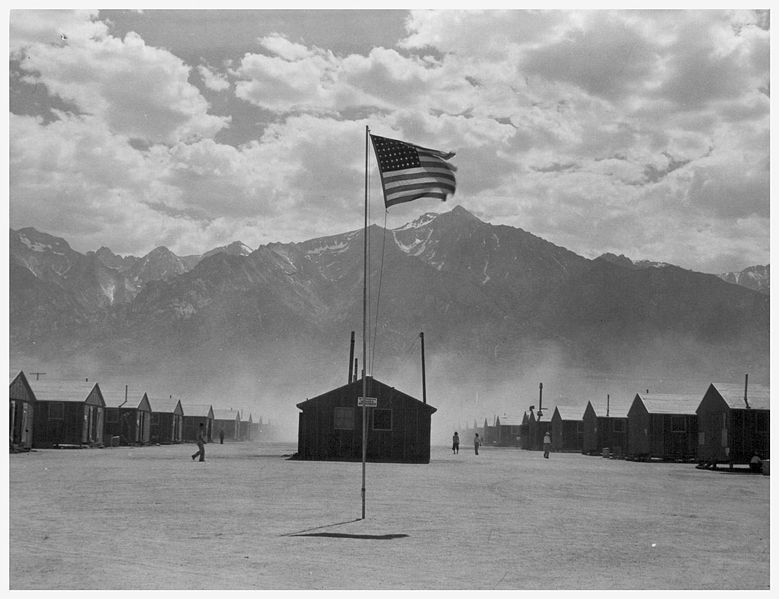

Some Objects At Topaz Internment Camp

While reposting those old Daddy Types entries about the US’s imprisonment of Japanese American citizens, I came across a couple of images of Topaz, Utah that were new to me. They were added to the University of Utah Library’s collection in 2012, and originated in a 1987 documentary about Topaz produced by KUED, the local PBS station.

The top image is sort of mundane, but the form of this make-do scrapwood sign just sticks with me. That might be an actual blackboard, or maybe not.

It doesn’t stick with me like the object in this image, though. Four unidentified people standing in front of the Service Flag for the “community” of Topaz, which included one star for each detainee serving in the US military. 325 at the time this photo was taken. Soldiers serving while their families were in prison because of politicians’ racial bigotry and fear.

KUED Collection of Topaz Camp photographs at the University of Utah Library [lib.utah.edu]

A Brief History of Blogging About America Imprisoning Children, 6/X

I’ll be honest, when I first heard that the ICE immigrant family detention centers full of Central American refugee kids and moms had animal-themed cell blocks like red bird and blue butterfly, I imagined they were using Eric Carle drawings, and I got a dark, blogging thrill.

But no. The South Texas Residential Center in Dilley, the largest family detention center in the world, run by the for-profit prison contractor, Corrections Corporation of America, was too cheap to license Carle’s work, and just used random clip art instead.

Also, the government’s punitive detention of these people is shameful, and it can’t end soon enough. Most of these families are fleeing war, violence, and abuse in their home countries and have already qualified for refugee hearings the US, but remain in these remote prisons, guarded by actual prison guards, temping in khakis and polo shirts, as a feeble deterrent to other refugees.

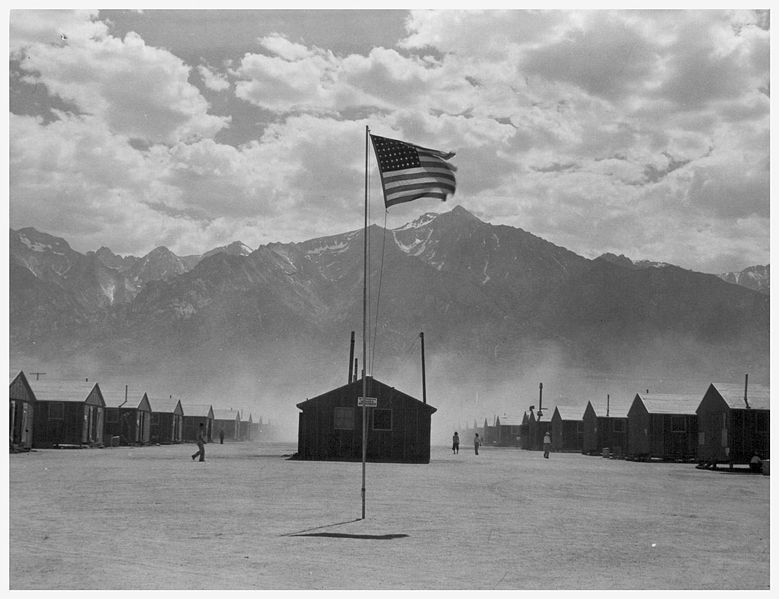

I resisted comparing ICE’s outsourced prisons to the desert detention centers Japanese-American families were forced into during WWII, even when I saw Bob Owen’s photo in the San Antonio Express News, which is a damningly straight-up evocation of Dorothea Lange’s photos of the War Relocation Authority’s internment camp at Manzanar, California.

Ansel Adams also took photos at Manzanar, which he published in a book, Born Free And Equal, alongside a text that reads today as disturbingly upbeat in its praise of the gumption and loyalty of American citizens forced into desert prisons. I’ve always viewed Adams’ project as a protest, a condemnation of the injustice visited upon Americans because of the racist fears of their neighbors and political leaders. But that is over-optimistic hindsight. Re-reading Adams’ text now is pretty depressing. To think that it’s all the Constitution and fundamental principle that wartime white America could handle at the time.

At least it helps make sense for how this country could get so cross-wise with its own professed ideals today; we really have not changed that much at all. And when I tried to put some evolved distance between the ironies of Adams’ treacly government-reviewed-and-approved fluffing and this account from inside Dilley, I couldn’t. So here it is:

While children wait for their mothers to talk to lawyers and legal aids, they are usually watching kids’ movies dubbed in Spanish, namely Rio or Frozen. The children of Dilley, like children everywhere, have taken to singing Frozen’s iconic song “Let It Go.”The Spanish-language refrain to the song “Libre soy! Libre soy!” translates to “I am free! I am free!” It’s an irony that makes the adults of Dilley uneasy. Mehta recalls one mother responding to her singing child under her breath: “Pero no lo somos” (But we aren’t).

Do you know the chorus of “Let it Go” in Spanish? I did not, but it is one helluva song for kids to be singing in a corporate prison in 2015:

Libre soy, libre soy

No puedo ocultarlo más

Libre soy, libre soy

Libertad sin vuelta atrás

Y firme así me quedo aquí

Libre soy, libre soy

El frío es parte también de míI am free, I am free

I can’t hide it anymore

I am free, I am free

Freedom without turning back

And I’m staying here, firm like this

I am free, I am free

The cold is also a part of me

‘Drink more water’: Horror stories from the medical ward of a Texas immigration detention center [fusion.net]

which is basically a re-reporting of this: Immigrant families in detention: A look inside one holding center [latimes]

Ansel Adams, Born Free And Equal, 1944 [loc.gov]

Related: Translating “Frozen” into Arabic [newyorker]

“Let it Go” in 25 languages [youtube]

[Originally published on Daddy Types on July 23, 2015 as Libre Soy, Libre Soy]

A Brief History of Blogging About America Imprisoning Children, 4/X

You’d think that as a parent, I’d be less surprised by now at the constant discoveries of the extent of my own ignorance.

And yet.

Last night, while surfing through the archive of the War Relocation Authority’s nearly 7,000 photos of WWII Japanese American internment camps for “furniture,” [right, I know.] I was confused by the number of search results that included George Nakashima and his daughter Mira.

The internment camps only imprisoned Japanese Americans on the west coast; Nakashima, modernist woodworking master, lived in New Hope, Pennsylvania, so he should’ve been totally unaffected.

But then, these Nakashima photos, which are all from 1945, have captions like, “The Nakashimas, formerly of Seattle and Minidoka.”

As if anyone is from Minidoka.

And it’s only then that I looked at Nakashima’s bio, and sure enough, the architect, his wife Marion, and his newborn daughter were expelled from Seattle and detained at Minidoka, Idaho in the Spring of 1942. It was only through the protracted petitions of Antonin Raymond, an architect and former employer, that the Nakashimas were able to leave the camp for Raymond’s farm in New Hope.

The picture above, by WRA photographer Francis Stewart, shows George Nakashima at Minidoka in the Fall of 1942, “Constructing and decorating model apartment to show possibilities using scrap materials.” Which, just. Wallpaper made from bookpages and blueprints and a proto-Conoid table made from prison scraps. This room should be in the Smithsonian.

The irony, if that’s the right word, is that it was at Minidoka that Nakashima met Gentaro Hikogawa, an issei hotel manager three years older than he, who’d immigrated from Shikoku to Tacoma. Hikogawa was also a master carpenter, who taught Nakashima Japanese joinery and rural handtool techniques that formed the foundation for Nakashima’s philosophy and later innovations.

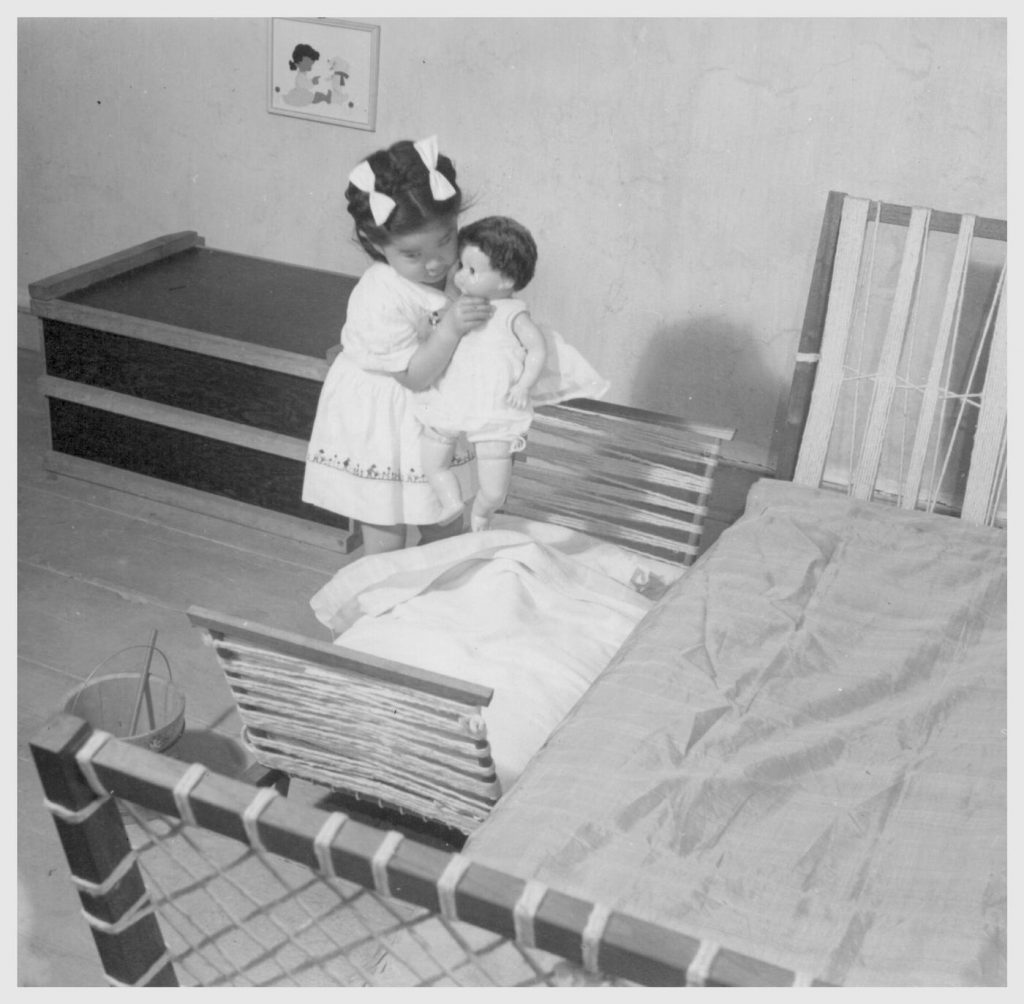

Speaking of which, here are two photos of 3-yo Mira Nakashima posing next to two beds her father made, one for her, and one for her doll, in her bedroom in New Hope.

War Relocation Authority Photographs of Japanese-American Evacuation and Resettlement, 1942-1945 [oac.cdlib.org]

[Originally published on Daddy Types on September 3, 2012, as George Nakashima and His Family Moved To New Hope in 1943]

A Brief History of Blogging About America Imprisoning Children, 3/X

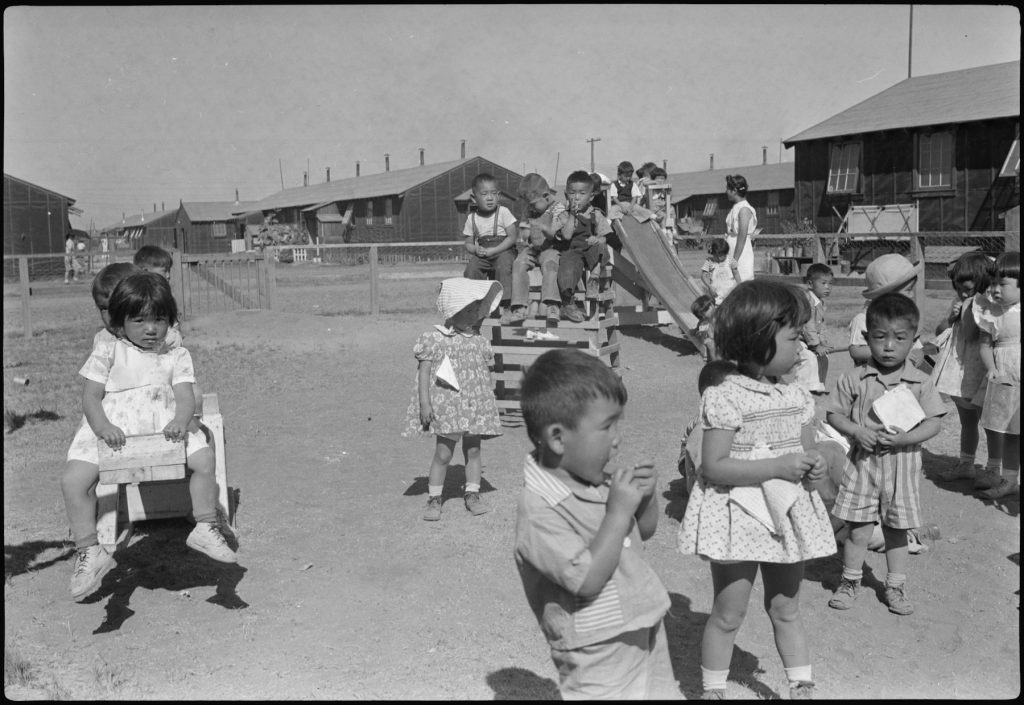

In WWII, Japanese Americans were forcibly removed from the west coast, stripped of basically everything they couldn’t carry, and imprisoned in inland internment camps, rows of tar paper barracks in the desert surrounded by barbed wire fences and guard towers.

Everything else, they had to build themselves. Here are a couple of photos from the War Relocation Authority collection at the National Archives of the preschool playground at the Tule Lake Relocation Center in Newell, CA.

Looks like they had better scrapwood at Tule Lake than at Topaz Mountain in Utah. Or maybe better carpenters. Still, I’d add that unfinished wood slide to the list of injustices perpetrated against loyal American citizen children by their government.

Previously from Tule Lake: Depressing Caption, meet Awesome Chairs

DIY Preschool & Playground, Topaz Internment Camp, Delta, Utah

[Originally published on Daddy Types on November 28, 2011 as Scrapwood Playground at Tule Lake Internment Camp. I also brought over a comment for this one.]

A Brief History of Blogging About America Imprisoning Children, 2/X

The photo blog on The Atlantic has been running extended looks back at images from World War II. Today’s theme: Japanese-Americans forcibly removed from their homes and businesses and shipped to internment camps in the middle of the freakin’ deserts.

The caption on #39 just bummed me out: “Nursery school children play with a scale model of their barracks at the Tule Lake Relocation Center, Newell, California, on September 11, 1942.” Their barracks.

On the bright side, check out the sweet little pine plank nursery chairs they’re standing on. How many civil right’s a brother gotta give up to score a few of those, I wonder?

World War II: The Internment of Japanese Americans [theatlantic]

Previously, and also September 11, 1942: DIY Pre-school Playground, Topaz Internment Camp, Delta, Utah

[Originally published on Daddy Types on August 22, 2011 as Depressing Caption, Meet Awesome Chairs

A Brief History Of Blogging About America Imprisoning Children, 1/X

America’s imprisonment of its own citizens because of racial bigotry during World War II has been of great interest to me since discovering Born Free and Equal, Ansel Adams’ self-published photobook of Japanese Americans detained at Manzanar, in the early 1990s. It always felt like important history that must be faced and not forgotten. Now, of course, it is a crime being surpassed and magnified, with families being torn apart and children fleeing for their lives being subject to state-sponsored terror at a scale this country hasn’t seen in almost a century, and all for the accumulation of Mautocratic political power.

It is not a sufficient response by any measure, but I am republishing a series of blog posts here which I made over the years at Daddy Types, the weblog for new dads, which I ran from 2004 until my CMS broke late last year. On DT I often wrote about the overlooked or forgotten histories and objects of parenting, with a focus on modernism, design, DIY, and dad-related projects. That included frequent posts on the material lives of Japanese American children imprisoned in detention camps during WWII, including the attempts to provide kids an approximation of a normal environment through schools, playgrounds, and domestic spaces built out of scrap lumber.

Here they are in chronological order. The first is a January 2009 post on the pre-school and playground at Topaz Internment Camp outside Delta, Utah. [2009 is when I learned my grandfather had helped build the Topaz detention center as part of the CCC.]

Continue reading “A Brief History Of Blogging About America Imprisoning Children, 1/X”

Better Read #023: Applied Ballardianism

This, the 23rd installment of Better Read, texts that are better read aloud by a computer, was inspired by a @ballardian tweet. It is the table of contents of Simon Sellars’ new sort-of-a-novel-sort-of-a-memoir, Applied Ballardianism, which is out this month from Urbanomic. As I type that out, I fear I transcribed it as Urbanomics. Fortunately, probably no one will listen to this. I should’ve kept my trap shut. [update: I did not.]

Order Simon Sellars’ Applied Ballardianism: Memoir from a Parallel Universe for £18.99 from Urbanomic or as an e-pub book from lulu. [urbanomic, lulu]

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

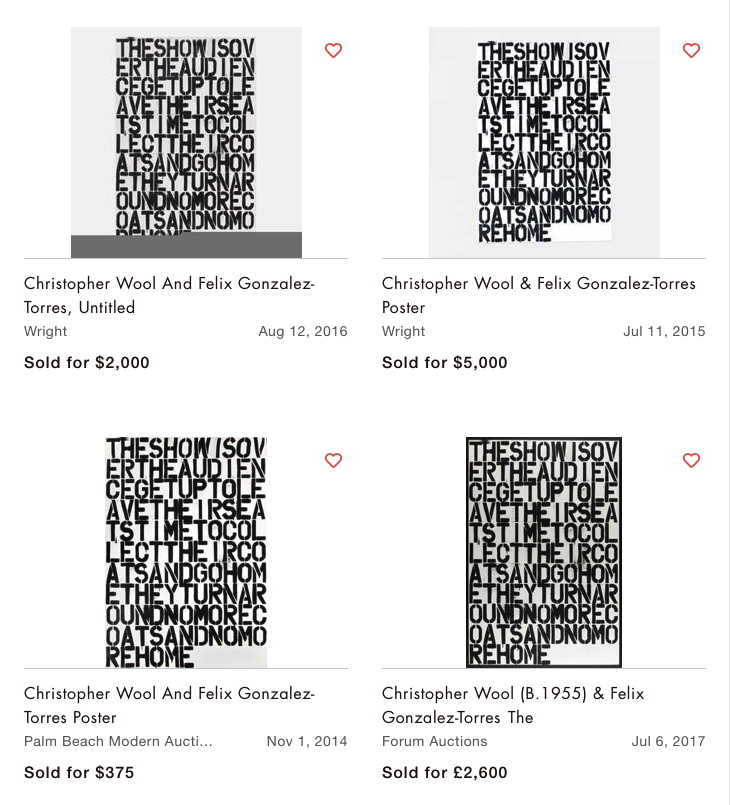

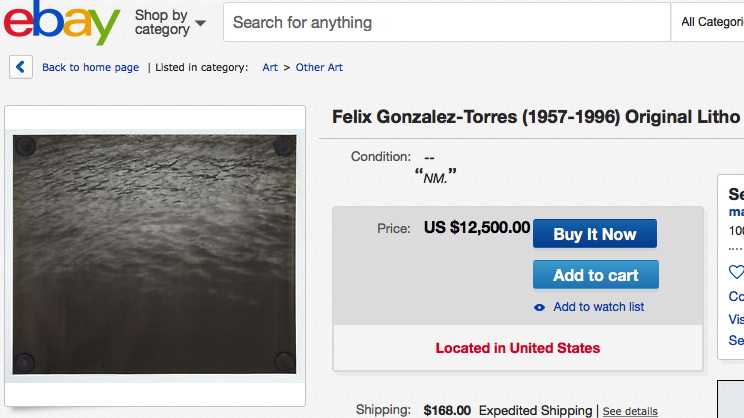

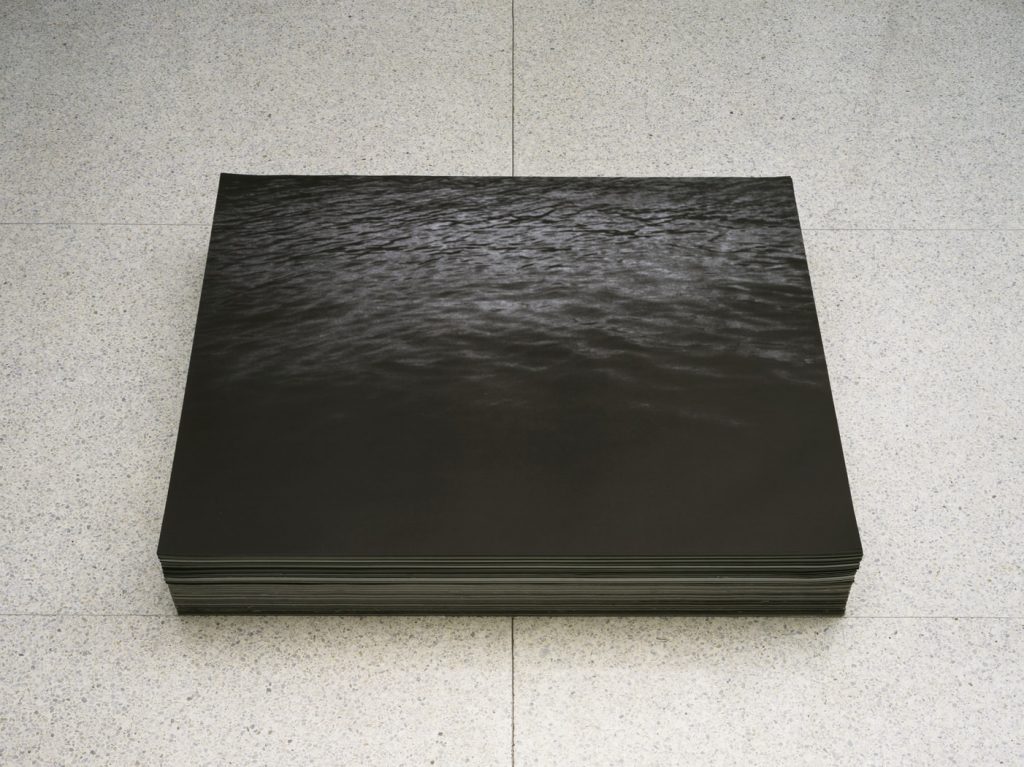

Art Sold Separately: Why Are People Buying Free Félix González-Torres Posters?

How much sense does this not make? People buy the sheets from Félix Gonzalez-Torres stacks at auction, on eBay, and at various artist book & ephemera dealers, and it just seems…what’s the word here? Hilarious? Sad? Stupid? Embarrassing? Ridiculous? Wrong? Inexplicable?

Well, no. There’s an easy explanation. People sell Félix posters because they want money. And people buy them because they are for sale.

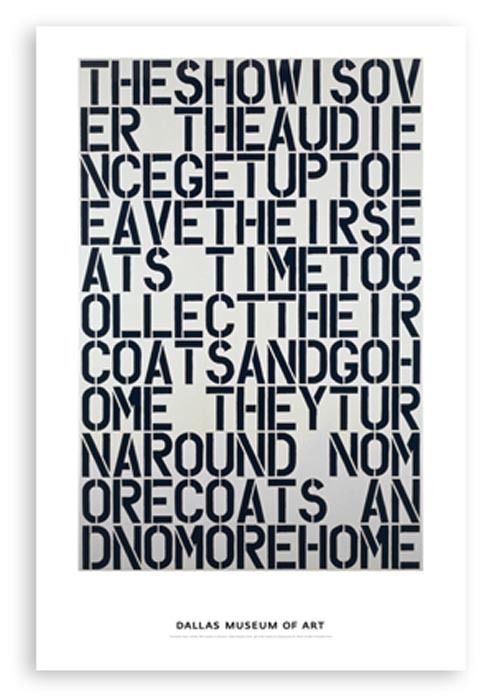

Félix made his first work that includes a stack of paper in 1988, and his first to consist of a stack constantly replenished with “endless copies” in 1989. Then there was a burst of stacks in 1990. By the time of his death in 1996, the artist had produced 47 stacks. Four were declared after his death to be “registered non-works.” One consisted of rubber doormats, which are not to be taken. One consists of an edition of 200 signed, silkscreen prints which together comprise a single stacked work, which are not to be taken. One was an edition of 250 of which 89 were sold separately, and the remaining 161 were sold together as a stack, which are not to be taken. The first one, it is not clear whether they can be taken. One is made of little passport-sized booklets, which can be taken. So that makes 38 stacks made of posters infinitely replenishable with endless copies. Along with a registered non-work stack created with Donald Moffett, three stacks were collaborations with another artist, who provided the image or text: Michael Jenkins, Louise Lawler, and Christopher Wool.

A part of the intention of the work is that third parties may take individual sheets of paper from the stack. These individual sheets and all individual sheets taken from the stack collectively do not constitute a unique work of art nor can they be considered the piece…its uniqueness is defined by ownership.

So these are not artworks. Or, they’re not the artwork. But they are something of value, even though they are free for the taking in an endless supply. And people trying to explain and justify the value–or the price, really–use paradigms that the artist himself critiqued, rejected, and sought, to some extent, to undermine. Sellers, including auctioneers like Wright who know what’s up, invoke an edition model, calling sheets “original” “prints” and “lithos” from “an unknown edition size.” This framing resonates with the investing community that has grown up around mass limited editions from print mills like Murakami and Hirst, Kawsian art toys and artist-designed skatedecks, and even Richter-style “facsimile objects.”

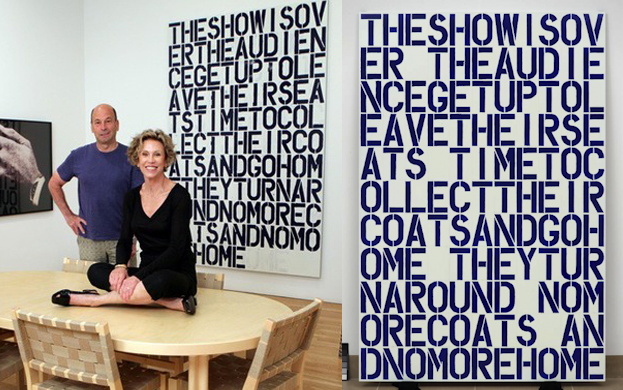

Rago, an auction house whose business is liquidating New Jersey’s vast collections of silkscreen editions assembled in the 60s and 70s, gives the sheets made-up names like “Untitled (water ripples)” and “Untitled (The Show is Over)”, and gooses the provenance with statements like “Created originally in 1993 for the Printed Matter exhibition at Dia.”

One eBay seller’s allusions to photography and rare book connoisseurship to justify a $12,500 asking price for a single sheet because it was taken from “the original piece” during a gallery show “in October, 1991,” have not gone unchallenged:

Please note that I have received some comments about this one… that is, since it was conceived of as an open edition, there are numerous ones out there from other exhibitions, and possibly a reissuance from the estate.That could be true, however, the original litho is a “first” printing; subsequent printings are of a subtlely diiferent (sp) size, color, paper, etc. This makes the first edition the most coveted, and hence the valuation.

Félix wanted as many viewers as wanted them to take sheets from his stacks for free, but this turns out to be not the same as free to obtain or endlessly available. They’re not all in publicly accessible collections. They’re not always on view, and they’re probably not close by when they are. So the constraints and complications of getting in a room with the Félix stack you want have real costs, and the way we weigh these costs against the desire to possess a thing is called money.

Then there’s the reality of the work itself, the stack whose “uniqueness is defined by ownership.” The artist’s certificates also say “The owner has the right to reprint and replace, at any time, the quantity of sheets necessary to regenerate the piece back to the ideal height.” There’s a concept worth studying in a work doesn’t just exist at various heights, but that depletes and is regenerated. If you find that dissertation, please lmk. What jumps out to me is the apparently fundamental link between uniqueness and authenticity and ownership, and the dependence of that existence on a right, not a responsibility.

For all the freedom and openness and sharing of Félix’s work, it rests on a foundation of rights granted to collectors, not obligations assumed by stewards. The market for sheets is thus the trickle-down effect of these private decisions that make stacks scarce through unavailability.

Could the artist’s wishes be better served by adapting his stacks to the digitized world he didn’t live to see? What if the Félix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation made all of the stack sheets available for download and individual printing? It’d be several kinds of complicated, I know, but it wouldn’t disrupt the existence of “the piece,” the uniqueness of which, remember, is defined by ownership. [Having recently pulled out around 100 sheets I’ve collected over more than 25 years, I can say this is not an obviously great idea; stacks vary in size, paper type, and finish in ways that DIY printouts will inevitably get wrong, and the artist’s generosity for everyone else’s shitty reproduction of his work will be sorely tested.]

Letting sheets loose in the wild will result in large-scale printing and distribution, probably at poster-scale commercialization. But a line in an eBay auction seems to indicate this is already happening.

After comparing it to a poster that sold for $750 on artnet, the seller of this $1200 poster “by Christopher Wool & Félix Gonzalez-Torres” notes, “NOTE this is an original edition from the Dallas Museum’s run and not from China.” But something ain’t right. The dimensions of the Wool&FG-T sheet are 37×55, and this one from Dallas is 24×36. Also, there’s a giant border, and it says Dallas Museum of Art on the bottom. Also, the letters don’t line up. Because this is a poster of a painting, a painting [right] the DMA acquired in 1991. Meanwhile, the related painting that became the stack is hanging [left] behind Thea Westreich and Ethan Wagner. They gave it to the Whitney in 2014.

Isn’t this the real source of the Felix stack flipper problem: hypeboys looking for cheap Wools? And at hundreds to thousands of dollars a pop, wouldn’t YOU set up a #ChineseWoolMill to meet their demand?

If there is such a thing as capitalist karma, it comes in the form of Erika Hoffmann, the Berlin collector who, with her late husband Rolf, bought the Wool/Gonzalez-Torres stack. In March she donated it, along with her entire collection, to the Dresden State Art Collection. It will become one of the most public and publicly available stack pieces of them all.

[This writing of this post was delayed several days by the outraged consideration of the vast preceding and ongoing corruption of the president, and it took place amidst the anguished, mounting fury at the systemic policy of terrorizing and torturing children and families seeking asylum from perils that drove them to flee their homes. The solace of art has its limits.]

A COUPLE OF DAYS LATER UPDATE: I swear I wasn’t planning to do this, but then someone on Twitter feared it was coming, and so it had to happen.

“Untitled” (Ross in L.A.) in DC is now on eBay. [update: it is gone.] It comprises an original Félix Gonzalez-Torres offset print acquired from the National Gallery of Art, and a full-scale, signed, stamped, and numbered certificate of authenticity. It is available in an edition of 2. [update: it is not.]

previously, related:

“Untitled” (Crystal Bridges), 2015–

“Untitled” (ArtEverywhereUS)

on the stack as medium, I loved this for annoying me so much: When Form Becomes Content, or Luanda, Encyclopedic City

It was a very sad time in our history. My mother was interned at Tule Lake, and to this day, she can’t talk about it without crying. It impacted her life, and therefore, the lives of her children and our children.