Insanely great article by Steve Silberman in Wired on John Gaeta and the CG–no, virtual cinematography–they developed for the Wachowskis’ Matrix sequels.

They created ESC, a “CG skunkworks company” for (at least) one fight scene, where Neo kung fu wire-dance fights with 100+ Agent Smiths. To shoot it, they created the world’s largest motion capture studio, ran the flying wire fighters through “hundreds of takes” per day, scanned Keanu and Hugo‘s heads with 5 HD cameras capturing 1Gb/sec of raw image data (400k/frame? Sounds reasonable, come to think of it…), and mapped the real world onto laser-measured wireframes. Short explanation: they created the Matrix. Oh, and they did it all in secret, using The Burly Man (taken from Barton Fink‘s doomed wrestling picture script)as their working title.

What this means for moviemaking is that once a scene is captured, filmmakers can fly the virtual camera through thousands of “takes” of the original performance – and from any angle they want, zooming in for a close-up, dollying back for the wide shot, or launching into the sky. Virtual cinematography.

I want one. I want one for my Animated Musical, where an intricately choreographed dance number could be viewed in one continuous, Fred Astaire-style take, and/or edited, with views from multiple animation-world “cameras.” It’d be great for editing, and you could make your own versions with the DVD.

Some related postings:

Matrix, The, video game/film convergence and

CDDb: Carson Daly Database

Gerry, the video game-like movie

Chicago sucked, and Moulin Rouge-y editing can’t help

Machinima and the (d)evolution of dazzling Steadicam

my tech/low-tech dilemma and an inadvertent slam on Gaeta, via his What Dreams May Come

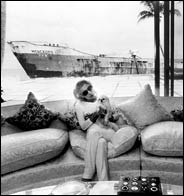

[Thanks, Boingboing. Image: Warner bros, via wired.com ]