Last week, in the Sony Classics offices on Madison Avenue, I sat down to talk with Errol Morris, whose current documentary, The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara, was nominated for an Academy Award.

Last week, in the Sony Classics offices on Madison Avenue, I sat down to talk with Errol Morris, whose current documentary, The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara, was nominated for an Academy Award.

Morris’s films are best known for the intensity of the interviews he conducts. He invented the Interrotron, a teleprompter setup that gets the interviewee to look and speak straight into the camera. I, in the mean time, didn’t have a digital recorder, so I decided to use a DV camera, the Sony VX-1000, to record our discussion. (Plus, that’d give me a chance to drop it off at the Sony Service Center downstairs to get the viewfinder fixed when I was done.)

I set the camera on the coffee table. Not only did I not get Morris looking directly into the camera, I ended up with an entire tapeful of Morris’s bouncing sneaker. Just as he did in The Fog of War, I structured our discussion around eleven lessons. [OK, fine. I went through the transcript and stuck eleven smartass lessons in as an editorial conceit. Close enough.]

Lesson One: Start an interview with an Academy Award-nominated director you’ve admired for fifteen years by sucking up. Big time.

Greg Allen: First congratulations on the film and the nomination. I should tell you, seeing Thin Blue Line in college was one of the reasons I wanted to become a filmmaker. It was so powerful and so not what you’d expect a documentary to be, especially at that time. So, thank you.

Errol Morris:

Thank you.

GA: With The Fog of War, a great deal of attention has been focused on the interview footage itself and what McNamara did or didn’t say, and was he going to take responsibility for the war or were you going to grill him about this or that. But your films have such a strong aesthetic and dramatic sense, which you achieve with other elements. I’d really like to hear more about how you go about making a film and what your process is for the putting those other elements together.

Lesson Two: I am a babbling sycophant.

EM: Very, very few people ever ask me about the film as a film.

I would say that almost all the interviews– 95% plus –focus on McNamara, and not on the film as a film.

It certainly is in keeping with other things I’ve done,

even though it is different,

there are elements in common.

Lesson Three: Errol Morris speaks with the measured, deliberative tone of his films. He’s a transcriber’s dream. Even if all you need know about typing you learned in kindergarten, you can get 95% plus of his comments in real time, no rewinding.

There’s an article written on Design Observer about the style of the movie. Did you ever see that?

GA: No, I’ll definitely look it up.

EM: www.designobserver.com..

GA: That’s great; I’ll track it down. Thanks.

EM: It’s someone speaking directly about the aesthetics and style of the movie,

a rarity.

Lesson Four: Errol Morris reads weblogs. At least weblogs about him.

GA: For visual elements like the dominos, or the maps, or the likening of the Japanese cities to American cities of comparable population, at what point did you know you were going to use those types of images?

EM: A lot of that is feeling my way through the material.

First of all, the material is driven by the interview.

The interview for me is like a script.

Sometimes during the interview itself, images will come to mind.

Certainly, McNamara talking about dropping skulls down the stairwells of the Cornell dormitory,

I immediately thought,

this is something I actually have to do.

Someone said to me recently,

in one of the few comments on the film,

they had written about slow-mo in film,

and how much they liked my use of slow-motion in all of my films,

including The Fog of War.

Lesson Five: There’s probably as much fast-motion as slow-motion in TFOW. In shots of Japanese streetscapes, frenetic time-lapse footage is superimposed over a slow-motion footage of the same shot.

EM: Part of it is this idea that we’re telling an internal story.

We’re telling a story about the inside of McNamara’s head.

And so the visuals, presumably,

should illustrate,

dramatize,

emphasize

themes that come out of what he says.

I’ve heard people say they don’t like the dominos.

I do like the dominos because

On one hand,

my editor Karen Schmeer and I would talk about this quite often

(she’s in her early 30’s):

her not growing up with the Domino Theory.

The Domino Theory was cause and effect.

One thing leading to another.

A kind of inexorability, as well as that straight interpretation of,

“if we lose Vietnam, we lose all of southeast Asia.”

The march of International Communism across the globe.

And I’ve done it in so many different movies–

A Brief History comes to mind:

the teacup coming together again;

the dominos going backwards.

To me, it’s a very important moment in the movie,

McNamara talking about counterfactuals.

Talking about “does history have to be the way it is, or could it be different?”

Themes, by the way, that are in every single movie I’ve made.

This interplay of fate and chance,

of the inexorable and the capricious.

And it’s in Thin Blue Line.

It’s in A Brief History.

It’s in Fast, Cheap

Lesson Six: When Morris talks about something, he uses a lot of phrases, fragments, that evoke something specific, that aren’t sentences, but that fit within a larger, overarching structure. Something bigger than a sentence. Now he’s got me doing it, too.

GA: I kept thinking back to the series you did, the TV series where you were interviewing people [First Person, which aired on Bravo], over and over there was this theme of someone almost unwittingly revealing themselves. Even after I thought I knew what was coming, there’d be this twist in this person somewhere. In the Fog of War, the imagery kept hinting at, or heightening or reinforcing the sense of McNamara’s own twisting and turning with himself. They seemed to link very powerfully, and underscored what he was saying.

EM: Yes.

GA:

EM: The imagery tells its own story, though, as well. We tried so many different things in this movie. So many things didn’t work.

Lesson Seven: Wow, Morris’s own interview technique of not jumping in himself to fill the silence really works. Maybe I should pare my thesis statements down a bit.

GA: Like what?

EM: Um, there were a lot of animated stills,

in the sense of stills turned into 3-D.

Only one of those remained in the entire movie,

even though we produced literally dozens of them.

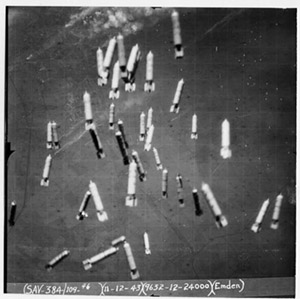

And that’s the shot,

going down through the bombs,

a moment of frozen time,

a sequence in Japan,

the numbers falling over Tokyo.

We tried that device in a number of different ways.

That was the sole instance that survived.

GA: You used more traditional documentary elements like the images of text and documentation, and the archival footage, too.

EM: Actually, it’s hard for me to know. I think that the Thin Blue Line has been very influential stylistically.

I’ve had people accuse me of being responsible for reenactment television, for infotainment television.

GA: [mock accusatorially] It was you!

EM: [mock culpably]It was me. “You’re the one!”

The reenactments have been widely imitated, but the use of graphics in the Thin Blue Line,

the use of close-ups of words,

or parts of an actual document,

is also something that has been imitated widely.

It’s now seen–

and I could be wrong about this.

I could have my history of the documentary confused and reinterpreted by myself in a self-serving way, I’m not sure

–but I believe my use of these close-ups was something that’s unusual and originates with Thin Blue Line.

So I like to think of it as not the convention, but something that’s come to be imitated widely.

Even by myself.

Lesson Eight: Asked about this, a film curator friend said maybe. Errol’s originality wrt text close-ups arises from his “incorporating CU’s into nonfiction filmmaking in a more theatrical, fictionalizing way, raising questions of objectivity and truth-telling.”

Lesson Nine: Errol Morris sees the world as orbiting around himself. Just like I do! Except that he’s more right.

GA: It gets to me every time I hear someone say, “Why didn’t he get this or that political nail in the coffin with McNamara?” from the very first shot, I felt I knew where you stood, the one where McNamara was at the press conference. It set the whole stage. You knew that this was going to be a movie about a man who was bent on controlling his message.

EM: It’s a movie about a control freak,

and you see him at the very outset,

controlling everything.

GA: When did you find that and decide to put that at the beginning of the film?

EM: Well, there were two, of course.

There were two moments at the beginning.

There was him setting up a 1964 press conference,

which actually comes form shortly after the second episode in the Gulf of Tonkin.

And then you hear him directing my interview.

GA: The more things change

EM: Exactly. So it’s–

I like themes being reiterated.

I like imagery being repeated.

It ties things together for me.

I like the punch cards, which are repeated in the movie:

once at the formation of the special group of people involved in statistical control in WWII,

and then again at the very beginning of his work at Ford Motor Company.

Yeah, these themes come back again and again of

Bombing, certainly, is a theme that runs through the whole movie.

I’ve had people–

quite a number of people

–criticizing me for not showing enough atrocity on the ground in Vietnam.

I like the idea–

because it’s part of the whole idea of McNamara and the movie

–that things are being dropped from the sky.

Whether it’s numbers

or skulls,

or bombs,

whatever.

It’s a kind of violence that is removed.

Part of the very nature of it.

It’s part of what makes it possible.

The fact that we are killing people at arm’s length becomes something where you can talk about being part of the mechanism.

Someone who pulls the trigger on a gun doesn’t use the kind of language that someone who’s involved in that kind of enterprise, that literally involves millions of people and complex machines, does.

GA: One of the things that I write about a lot is the current administration’s very sophisticated image crafting. Everywhere Bush goes there are carefully placed billboards with “jobs” or something written on them, and they set up the soldiers like extras in the background, carefully framing every single setup for the press pool cameras.

When I saw that first shot of McNamara prepping the map for the camera, it’s something that clicked with me again, the penchant for controlling and setting an image as part of the process.

EM: One of the things about photography that fascinates me–

whether it’s still photography or motion picture photography

–is that there’s always an element of control,

and there’s always an element of things that can’t be controlled.

There’s an element of spontaneity,

and an element of things which are completely unspontaneous.

Lesson Ten: Whoa, this sounds like the free verse poetry of Donald Rumsfeld.

One of the remarkable characteristics of those presidential recordings [of JFK and LBJ in Fog of War] ,

is that so much of what we see of the president is manufactured,

is controlled,

is staged,

managed,

maneuvered,

that to actually hear the president of the United States in a different context,

speaking extemporaneously,

is in and of itself really unusual and surprising.

It’s trying to see beyond the corners of the frame.

GA: The next time we meet, I’ll try and bring my iPod with the microphone attachment, in your honor, instead of this camera.

EM: I love those. I have two, one here in New York and one at home.

Lesson Eleven: Shoot a bunch of commercials for Apple, score a pile of gear.

GA: Cool. In the mean time, I have to wander the halls until I find someone who can service my camera.