[NOTE: Though the use was more common at the time, I grew uncomfortable with the racist origins and implications of the colloquial use of “ghetto” for these works. I changed it to “shanzhai,” a Cantonese term which originally described unabashed counterfeit consumer goods; this usage has since shifted toward a hackier, scrappy innovation, but for these works, the original meaning pertains. I have kept the original uses of ghetto rather than delete them to acknowledge the blinkered social context I was also complicit in.]

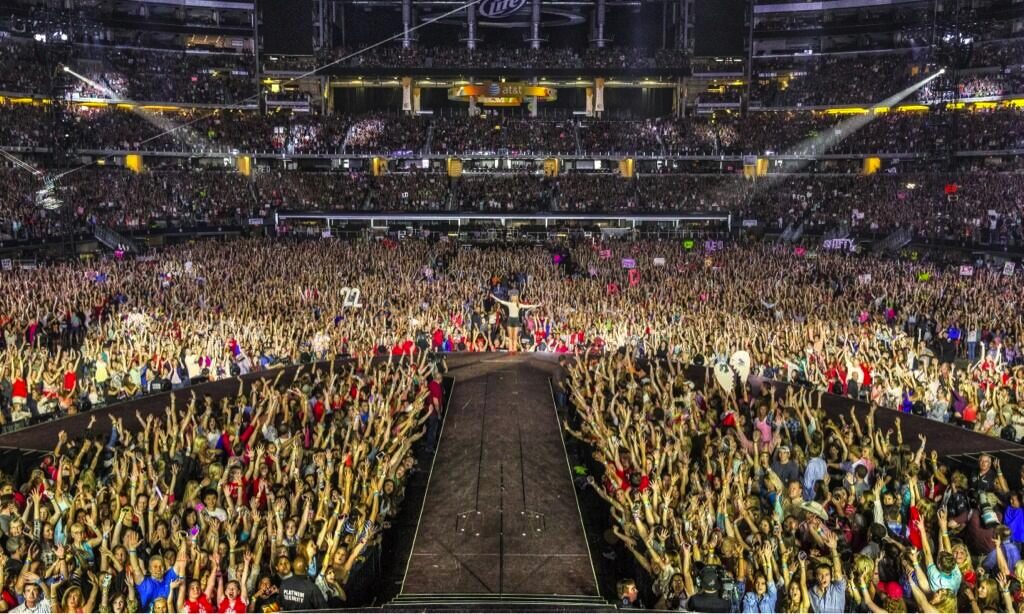

Seeing Brent’s tweet of a Taylor Swift photo yesterday made me finally move on an idea that’s been percolating for several years: the Ghetto Gursky.

The new Gursky. RT @taylorswift13: Dallas. Thank you for a memory I’ll replay in my mind on rainy days. https://twitter.com/taylorswift13/status/338877935069036544

— Brent Burket (@HeartAsArena) May 27, 2013

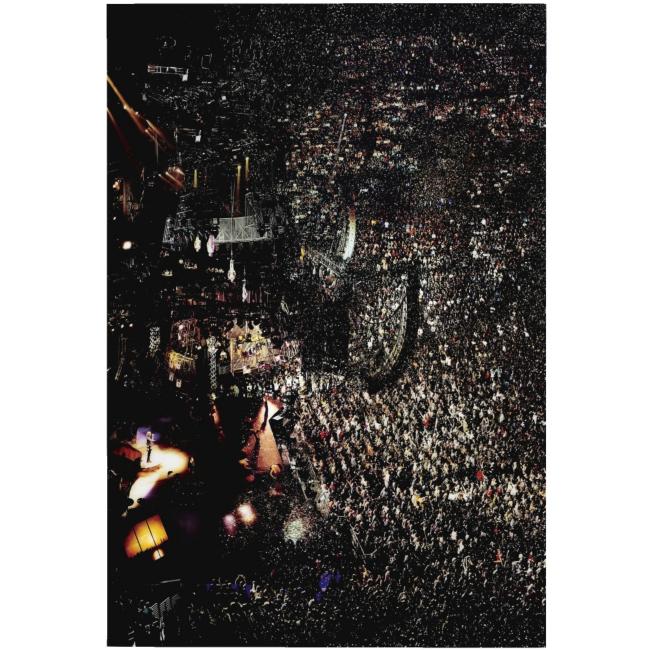

The Swift-as-Gursky image is key, in a way. I had kind of a falling out with Gursky’s work in November 2001, when he was shooting Madonna’s concert tour (in LA, on Sept. 13) instead of what I felt he should be shooting: the wreckage of the World Trade Center.

Madonna I, 2001, ed. of 2

I’d been morally invested in Gursky’s work [I was not alone at the time] and its presentation as a critique of the globalizing forces and systems in the world, and I’d wanted to see his take on what seemed like the most pressing reality of the moment:

From the first week after the bombings, when I was in full CNN burnout, I wanted writers’ and artists’ perspectives, not Paula Zahn’s. The scale of the debris, the nature of the target, even in wire service photographs, it called for Gursky’s perspective to make some sense of it, perhaps.

Because I realized even then it was an idealistic and presumptuous view of art, and it was based on no actual knowledge of Gursky’s practice of artmaking. But it distanced me from the work, and germinated the seeds of skepticism that had been planted at the end of Peter Galassi’s 2001 MoMA retrospective.

The last gallery of that exhibition featured ever more massive prints, with ever less subtle Photoshop manipulations, culminating in a collage of disembodied CEOs and boards of directors floating against an abstract background. I remember thinking at the time how awful it was, and wondering where Gursky was heading–and whether Galassi had any qualms about showing the stuff.

Gursky has certainly made much better work since, but it stuck with me then how closely linked the impact of his work is to the state of the technological art and the means of production at any given moment. He was a Becher alum interested in exploring the latest developments in large-format photo printing and digital manipulation. The effect and experience of this can be stunning, but it can also be a trap. When you’re selling spectacle and production and wall presence, you have to keep up with the Struths, as well as the dozens of other artists who figure out where the 5-foot wide printers are. And the 8-foot. So there’s that.

99 Cent “Like Warhol, Gursky has succeeded in seducing his viewers with his product.” –Phillips de Pury, Nov. 2006

And then a few years later, while working on a story for the Times, a collector offhandedly mentioned a market for Gursky exhibition prints. Which kind of surprised me. Because now there was a tension between the arbitrariness and fiction of the photographic work’s edition size, and the physical reality of these giant, expensively produced, museum-grade [obviously] objects. And the tension played itself out in, or was really only a problem for, the market, where at that moment, Gurskys at auction were the most expensive photos in the world.

Which is right when I was chatting with another collector in Miami, as we toured the family’s house during an ancillary Art Basel event. Introduced to her as a fellow collector with an interest in photography, she asked, “Do you collect Gursky?” And suddenly Gursky was stripped bare, transformed into [or revealed as, depending on your cynicism] a pure commodity, the apparently socially acceptable way of straight up asking someone their net worth. And of demonstrating your own.

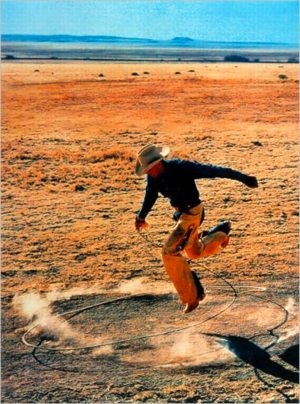

Untitled (300×404), 2009, published in 2010 by 20×200

In 2009, when I printed up copies of Untitled (300×404) using a small JPG of a Richard Prince Cowboy photo, I was interested to see what the difference was between his real, appropriated artwork and the digital image we were “allowed” to access by copyright [and gallery/institutional exercise of control].

The 20×200 editions of Untitled (300×404) got me thinking about how art discourse and the market handle [or don’t] issues of authenticity and copying, where the value lies, and where the attention is directed. And the extent to which money, class, rarity, and luxury color our experience of art, even when we claim self-awareness and critical resistance, and even if the artist seeks to thwart such influences in the reception of her work.

And I thought on the existence of quasi-illicit, out-of-edition Gurskys infiltrating the market in a don’t ask, don’t tell way, ably performing their functions as markers of capital and luxury objects. And how it was acceptable to ask if you collected Gurskys, and even when you started, but not to ask how much you paid, or how big a discount you got, or what number this here Gursky was in the edition.

And I wondered how close you could get to the experience of standing in front of a Gursky, the encounter with the artwork, the image and scale and finish and physicality of the object itself. What would happen to the rest of the experience? Could a Gursky ever generate a genuinely critical encounter of the system that has spawned it, from within that system?

And that’s where the idea of the Ghetto Gursky came from: a full-scale recreation of the Gursky Experience, made with publicly available imagery and publicly available production technology. Which, by the way, has become widespread, if not commonplace, in the decades since Gursky began using it.

What would such a commonly produced object do to the socioeconomic aura of the originals? If a Gursky were a sign of significant wealth and sanctioned taste, what would a Ghetto Gursky be a sign of? Clueless and failed aspiration–the contemporary art equivalent of putting an elaborate copy of Michelangelo’s David by the pool? We can call this the outcome the Carlos Slim. Or would it be a way to show off the modesty of one’s means? The Art Basel cheer of absolutely no one, “Hey, I have five thousand dollars!”

The polarization of the art market is such that a Ghetto Gursky has less justification for existing, and less likelihood of being sold, than a real Gursky. Which seems ridiculous. So I decided to go ahead and make one and see what it’s like.

Rhein, 1996, blown up 4x from a thumbnail for effect

I’ve ordered a full-size print of Gursky’s 1996 photo Rhein, which is being made using the largest jpg version of the image I was able to find online. Then I’ll have it mounted on Perspex and framed, just like his original. This is not Rhein II (1999), which is like 2×3.5m long, and is currently the most expensive photo sold at auction. [An edition of Rhein did just sell at Phillips a couple of weeks ago for $1.9 million, which is not nothing, but still.]

Rhein is only around 5×6 feet, big when it was made, but now, not really, which is kind of the point. It’s also a more manageable size to experiment with. It will fit on my wall and in my car and in my storage. Katy Siegel wrote in 2001 that “Gursky’s motivation is the masterwork, the valorization of the fetishized object of high art.” A Ghetto Gursky will invariably be as heavy and large and unwieldy and difficult to transport, store, and hang as a real one, which only contributes to its implausibility. Which is kind of the point.