The “What art should the Obamas hang in the White House?” story rolls slowly onward. Last week in ArtInfo, Ruthie Ackerman published the suggestions of several of the art world’s greatest minds. Greatest among equals, obviously, is Magda Sawon of Postmaster Gallery, whose list began,

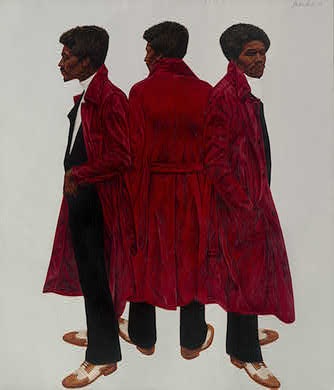

“I am seconding Greg Allen of the brilliant blog greg.org to bring Sir Charles aka Willie Harris (1972) by Barkley Hendricks to the White House. It’s a tremendous painting from a still-under-the-radar master that puts Kehinde Wiley to shame.

Hear, hear!

Now that we have consensus, let’s move this plan forward, shall we? The National Gallery of Art brought Sir Charles into the collection in 1973, along with another remarkable Hendricks portrait, George Jules Taylor. Neither have ever been shown in the National Gallery itself, though both are included in “The Birth of Cool,” the highly acclaimed Hendricks retrospective organized by Trevor Schoonmaker of Duke’s Nasher Museum of Art.

By the criteria the Obamas set for themselves, that means the works couldn’t come into the White House until they go back out of public view, 2010, after the retrospective winds up in Houston. Plenty of time to make the case for this awesome painting; let’s take a closer look at it!

Duke art historian Rick Powell explains that Sir Charles was the professional name of a Dixwell Avenue drug dealer in New Haven whose customers were mostly students from the little college a couple of blocks to the east, where Hendricks was studying for his MFA. The Willie Harris reference, meanwhile, is from A Raisin in the Sun; like that fictional Harris, Powell says, Sir Charles “would frequently disappear with [his customers’] money.”

Hmm, could the Obamas ever really bring themselves to hang a painting in the White House of a small-time, money-thieving, pimped out, drug dealer–from Yale??

Hendricks described Sir Charles’s style as “player chic,” which the ever-proper Powell feels compelled to address at some length:

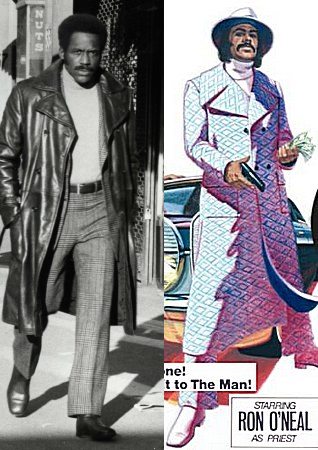

While the term “player chic,” hinting at illicitness and misogyny, points to the ostentatious fashion statements of pimps, street hustlers, and other disreputable members of a black demimonde, the same style of dress–platform shoes, body-hugging jumpsuits, leather pants and maxicoats, real and artificial fur–was worn by a broad spectrum of African Americans. Most were not connected with life’s shadier side, but many did feel an affinity for this provocative “outlaw” persona. The most obvious broad-based celebration of the “player chic” aesthetic in the early 1970s was the commercial success of Super Fly (1972), a feature-length film directed by Gordon Parks Jr., about a drug dealer who undergoes a change of heart…

Uh, not to quibble, but wouldn’t the phenomenal critical and financial success of Shaft, made in 1971 by Gordon Parks Sr., count as a broad-based celebration of player chic, too?

in which case, wasn’t the swaggering black male “outlaw” archetype thoroughly established, even romanticized in popular culture, making Hendricks’ choice of Sir Charles as a subject a little less transgressive or controversial, at least among the edgier liberal audiences at Yale and–

Wait a minute, where was Hendricks’ audience? The guy was still in art school when he painted these things in 1972, and then they were in the National Gallery a few months later? How’d that happen?

Stay tuned.