So Knoedler Gallery’s Ann Freedman didn’t only traffick in forged Motherwells and Pollocks; she moved a couple of fake Barnett Newman paintings, too. But, I guess, because the owners of them didn’t sue, we haven’t seen images of those works. Which doesn’t mean they’re not out there. Or that they haven’t been seen. In fact, at least one Newman painting was included in a high-profile gallery exhibition in New York, and at the Guggenheim in Bilbao, making it one of the most prominent paintings in the whole Knoedler forgery scandal.

The details come from the complaint filed by Freedman earlier this month as part of a defamation lawsuit against dealer Marco Grassi, which Art Market Monitor has posted. Freedman sued Grassi for giving a fairly nonspecific quote about how she hadn’t done her due diligence before selling dozens of previously unknown AbEx masterpieces brought to Knoedler by Glafira Rosales. I’m struck by how incidental Grassi’s actual comments are, especially compared to the extensive details which Freedman lays out in her complaint. It’s almost like she is suing someone just so she can inject her version of the facts into the public discourse on the case, attempting to bolster her own claim that she’s a victim of Rosales’ deceptions, not a collaborator or enabler.

And so Freedman goes artist by artist, describing all her gallery’s research efforts, and piling up the comments and credentials of the art world experts she says saw–and praised, i.e., authenticated–the Rosales paintings. She mentions two Newmans. For Untitled (1949, a 59×34-in Newman canvas, the list included Ann Temkin, who curated the Philadelphia Museum’s Newman retrospective; Richard Shiff, who co-authored the artist’s catalogue raisonne; directors and curators from the Albright-Knox, who she said tried to acquire the painting; and the National Gallery’s Harry Cooper:

These experts and scholars likewise believed in the authenticity of this painting. For example, when Cooper viewed it, he stated that it was “beautiful” and “bore a relationship to the feeling in Stations of the Cross,” a well-known Newman work.

“Believed in the authenticity of this painting.” Imagine Freedman, the president of the oldest art gallery in the country, hosting a group of museum officials one evening in 2007, and then asking them what they thought of the Barnett Newman piece she’d just hung. If they asked where it had come from, she’d have said, what? From a private Swiss collection? Who would be the one to cast doubt on the authenticity of the painting in that context?

Another expert was even more deeply involved with the 1949 “Newman,” though; art historian David Anfam included it in his 2008 show, “Abstract Expressionism: A World Elsewhere,” that inaugurated Haunch of Venison’s New York space after Christie’s purchase of the gallery. The exhibition, stuffed with works borrowed from both museums and other dealers, was technically a non-selling show, though as Roberta Smith’s scolding review noted, Haunch of Venison’s statements on the matter were coy, dissembling, or both. Smith counted a dozen, but based on the number of gallery-organized loans, I figure at least 30 of the 62 works in the show could have been for sale. And sure enough, in Freedman’s lawsuit, she says that Anfam had “eagerly marketed [the Newman he borrowed] to potential purchasers.”

[MAY 2014 UPDATE: The NY Times’ Patricia Cohen cites unspecified court documents to describe how fear of litigation kept skeptical scholars from speaking out publicly, but it didn’t shut them up entirely:

And in June 2008, months after Dedalus started asking questions, three Barnett Newman experts — John O’Neill, Carol Mancusi-Ungaro and Yves-Alain Bois — concurred that what was said to be a Newman, from Knoedler, hanging at the Beyeler Foundation in Switzerland was a fake. But as Mr. Bois wrote in an email to the Beyeler, he and his colleagues were “told not to make a public announcement” by a lawyer for the Barnett Newman Foundation, who feared a lawsuit.

June 2008 would be Art Basel season. I can’t see what exhibition at the Beyeler might have included a Newman, though.]

Smith’s review mentioned “an unfamiliar Newman” as a worthwhile element of the Haunch of Venison show, but there was none visible in installation shots online. [And of course, Christie’s deleted HoV’s website after the gallery was folded into the auction house’s private sales division.] So I headed to the Strand to pick up a remaindered copy of Anfam’s catalogue for the show.

In his essay for a New York School show in New York, blocks from dozens of well-known masterpieces on constant view, Anfam said he sought works that provided “freshness and variety.” So “a hitherto almost [sic] unknown Newman from his annus mirabilis of 1949″ must have fit right in.

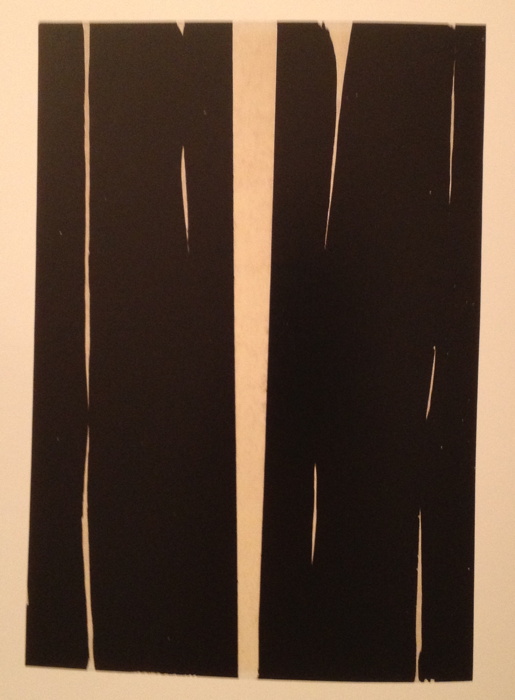

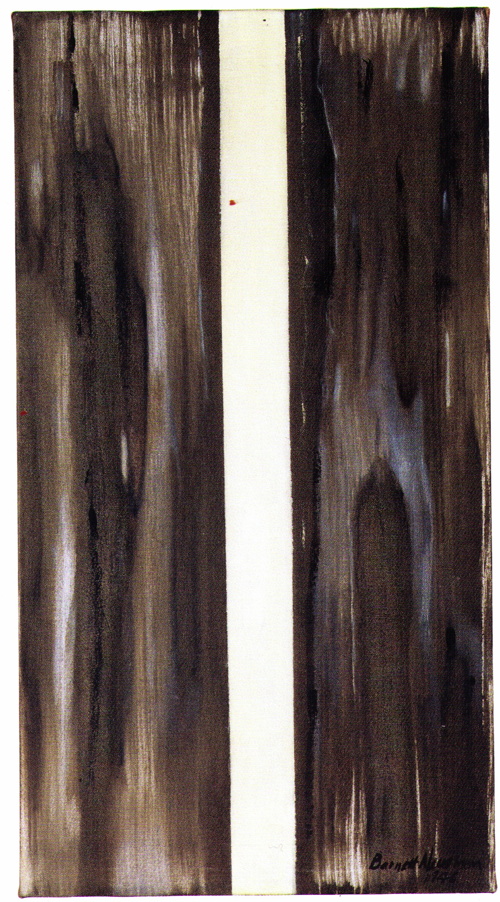

Whatever my original interest in seeing what a successful fake ur-Newman looked like, it couldn’t compare to the odd sense of skeptical anticipation I had flipping through the catalogue. There were four Newman’s in Anfam’s show, and as I saw each one, I wondered if it was the fake.

It didn’t matter that I had the title and dimensions of the forgery; suspicion still tainted that first look. The expectation of uncovering a forgery had me questioning every work, searching for anomalies. That zip didn’t look right. The brushy, translucent fields are obviously off. That’s just a poorly proportioned copy of a classic. And in each case, of course, the work turned out to be an authentic Newman with immediately unassailable provenance. The Newmans Newman had painted had been set at odds with my mental image of what a Newman “should” be.

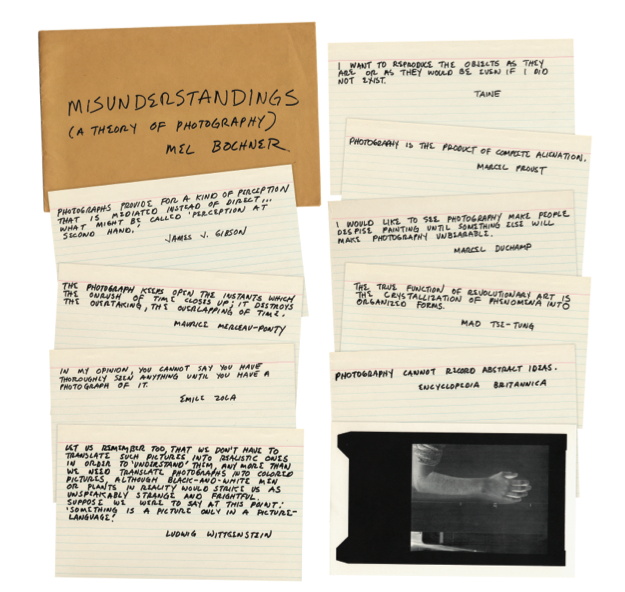

It reminded me of Mel Bochner’s contribution to the “Artists & Photographs” box published by Multples, Inc. in 1970, titled Misunderstandings ( A theory of photography). Bochner had been collecting quotes about photography on note cards, which no art magazine had wanted to publish. When Marian Goodman asked him for a piece, he mixed six of the quotes with three he made up on his own. As he told triplecanopy & rhizome in 2010:

To this day, I have never revealed which are which. Under the principle “One rotten apple spoils the barrel,” the intention of this act of forgery was to undermine any possibility of belief in the text. The “groundlessness” of the quotations became the equivalent of what I viewed as the groundlessness of photography itself, focusing attention on the artificiality of any framing device. I saw this as an attack on one of the main tenets of minimalism, Frank Stella’s claim that “what you see is what you see.”

What you see is what you see. The Knoedler forgeries blow that up both coming and going.

I’ve tried to preserve, or at least approximate my sense of doubt here, by not captioning the images from the HoV catalogue. I’m sure you can figure it out, though, even without doing math or looking at img file names. It’s one of those “Now that you mention it” moments. The others are, of course, unassailably authentic, with provenances and documentation and history that only emphasizes the Knoedler painting’s complete lack of the same.

And meanwhile, the other Knoedler/Rosales Newman, Untitled (1950), is still a mystery. Like the 1949 forgery, it was selected for a 2007-8 show organized by the Guggenheim and Terra Foundations titled, “Art in the USA: 300 Years of Innovation,” but it ended up staying home. [Though the show also traveled to Moscow, Shanghai, and Beijing, Freedman’s complaint only says that Untitled (1949) went to the Guggenheim Bilbao.] Anyway, I hope (1950)’ll turn up, too.

Meanwhile, I’d like to make an open offer to the current owner(s) of the Knoedler/Rosales Newmans, to buy them for a fair price. Assuming they can be authenticated, of course.