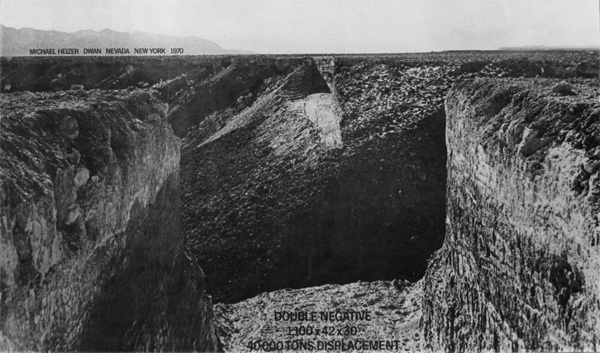

One of them, anyway: Michael Heizer Double Negative, 1969, south side, where the calving of boulders and sediment is becoming significant. image: August 2016, greg.org

There is so much about Sturtevant I don’t know, and it amazes me every time I find out something else about her and her art.

For example, have you read Bruce Hainley’s book about Sturtevant, Under The Sign of [sic]? Of course you haven’t, because if you had, the other week when that New Yorker profile of Michael Heizer came out, ALL you would have been thinking and tweeting and yammering about was Sturtevant’s Heizer Double Negative.

I repeat, Sturtevant had a project to repeat Michael Heizer’s Double Negative, within months of Double Negative‘s unveiling, and it was called Heizer Double Negative.

And it would have been NEXT TO Double Negative. Let’s read on.

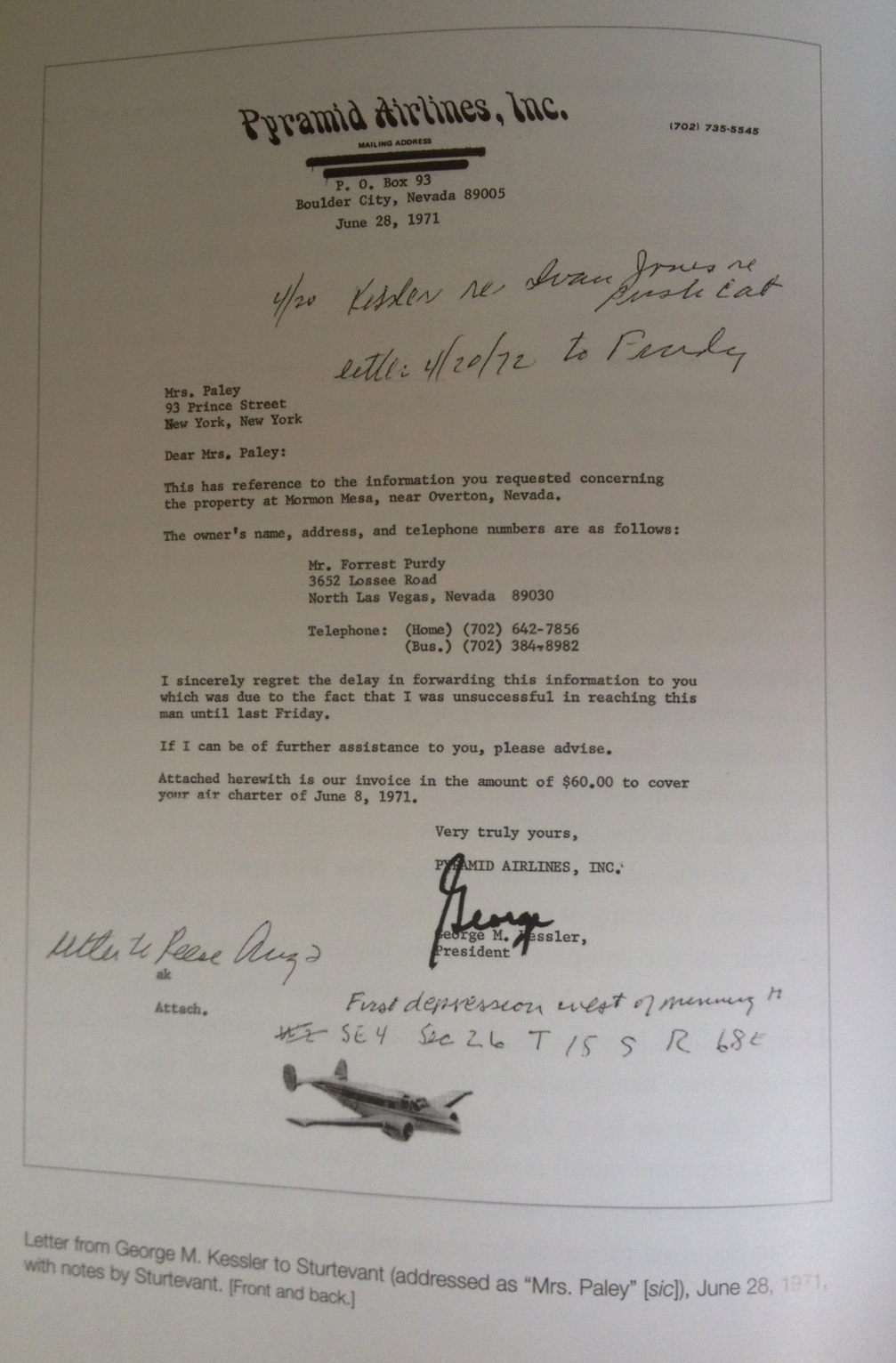

Hainley publishes a letter from SoHo dealer Reese Palley dated January 15, 1971, which gives the first date for the project. “You’re an exciting broad,” Palley writes, “but I don’t have to tell you that; you know it.”

In early June 1971, Sturtevant travels from Paris to Las Vegas for a scoutabout. She goes as “Mrs. Paley” [sic] so she can use Reese’s credit cards. She charters a plane for a surveying trip. She gets together a list of road and casino construction contractors and earth movers. She has her charter pilot research up the local property records and contact the owners of the land she wants to buy. Everything’s a go, Mr. Palley back in New York is putting together the financing. 1971.

Exhibition poster, Michael Heizer, Dwan Gallery, Jan 1970, image: Artforum

Heizer created Double Negative on the east edge of Mormon Mesa above Overton, Nevada, where the Virgin River begins to widen into Lake Mead, in 1969. The work was unveiled at Dwan Gallery in January 1970. The show was called

“Temporary Exhibit, Jan., New York

Permanent – Nevada”

Two photos of Double Negative were among the seven images on the checklist. At least one was mosaicked together like NASA panoramas of the moon. [There were also two large-scale transparencies on plexiglass titled, Sunset – Nevada.] Dwan made clear the work was not conceptual. “I have to explain that anybody can see it simply by going to Nevada, and that when an artist has moved two hundred and forty thousand tons of dirt around, it is not just a concept.” That was what she told Calvin Tomkins in 1972, [note: the original exhibition material says only (sic) 40,000 tons were displaced.] but the impression is understandable and inevitable, because photos were the context of Double Negative. Images were the entire experience of almost anyone who saw or knew about the remote piece. It was the moon landing of art.

Lawrence Alloway reviewed the show for The Nation:

[Heizer] presents documentation of an earthwork in Nevada. The original looks marvelous, but the information in the exhibition could be put on a postcard. Blown-up photographs and captions do not an exhibition make. The problem of documentation is apparently on Heizer’s mind; at the Whitney Annual there is a big transparency embedded in plastic of an absent work. His works exist convincingly (1) on site and (2) in documents, but his effort to move into a third domain of exhibitable objects has not worked yet.

[Emphasis added for relevant considerations of originality and the nature of art’s existence.]

As Sturtevant discussed with Hainley and Michael Lobel in 2007, Heizer Double Negative was “not realized” [sic mine]:

MS. STURTEVANT: Ran out of money. I wish I had done that. I wish they hadn’t run out of money. That would have been such a big high.

MR. LOBEL: So what were the circumstances around it? Who ran out of money?

MS. STURTEVANT: Reese Palley [Gallery].

MR. HAINLEY: Reese Palley.

MS. STURTEVANT: But Reese Palley’s lawyer’s the one that said, “Forget it, you don’t have the money to do this.” So.

MR. LOBEL: And so you actually did work around see –

MS. STURTEVANT: Well I had, I had located the land that would work, yeah, yeah. And I had the land plot. And yeah, no – and I had contracted the Caterpillar people and – pity. But you know then, also, you have to totally maintain those things, and I wouldn’t have had the money to do that anyhow. They have to be maintained because they get filled again. But that piece is so strong, that Double Negative.

And talking about negatives, see, negative is a very strong force. I – phew – I think it’s very powerful, and it’s not powerful because it’s negative; it’s powerful because of what its force is. Yeah. So it’s very different. Yeah, that can be very strong.

It was not realized, but also so strong, so powerful, so not not realized, either. Double negative. Double Double Negative.

image via Hainley’s Under The Sign Of [sic]

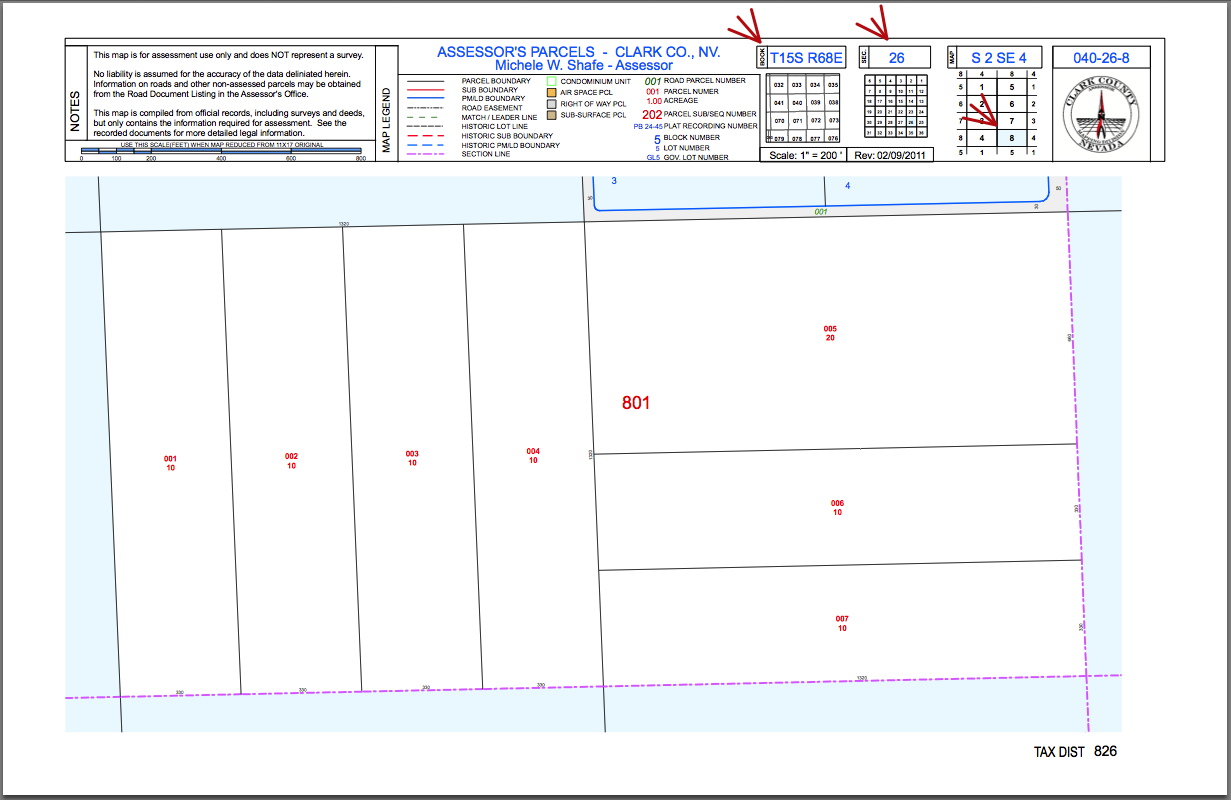

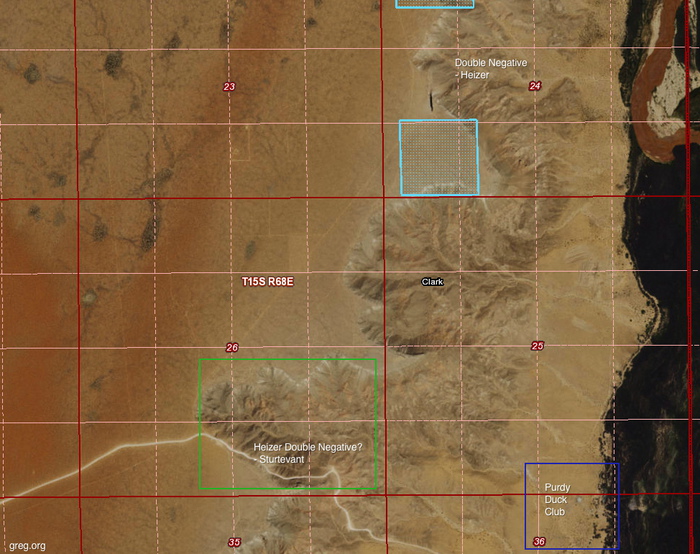

After reading and thinking about it for nearly three years, I decided to visit Sturtevant’s Heizer Double Negative. I got back a couple of weeks ago. Hainley’s book has the pilot’s letter with Sturtevant’s coordinates for the site. He calls them latitude and longitude, but technically, they’re the section and square numbers from assessors’ maps. You can search them on Nevada’s State Managed Lands map, and cross-reference parcel ownership and history in the Clark County Assessor’s database.

[One thing I didn’t really think much about until I freaked out for a second about it when I looked at the tax records: Double Negative itself is constructed on two separate parcels; the south one is 20 acres, the north is 40 acres. MOCA owns both, obviously, but not any of the parcels adjacent, which are owned by a variety of private parties, and one government entity. One parcel that meets the north half of Double Negative at a corner actually sold last year. For $10,000, barely the cost of one gala ticket. MOCA didn’t buy it. After my Jetty Foundation experience, I was thoroughly unsurprised and ready to grab a pitchfork, but when I got to Double Negative itself, I realized that parcel is down the backside of another ravine, and poses little or no aesthetic threat to the work. I am sure that’s what MOCA was thinking, too, when they didn’t buy it, and that they’re primed to acquire buffer land around Double Negative the way Dia did for Walter de Maria’s Lightning Field when Philippe was ever-prescient director there. That’s what I call a double positive.]

One problem arose. The maps and tax records don’t quite match to the owner name Sturtevant’s pilot turned up. Forrest Purdy owned a lot of land in Nevada, but I can’t find any record of him owning plots in the section and squares Sturtevant wrote down. He did own land one section over, and one down, in 25 and 36. But that’s not on the mesa; it’s down on the Virgin River. Purdy apparently built [sic] a private duck hunting club there in the late 70s and 80s. He set up a couple of sheds and blinds, then he dug a channel to bring the river-and, ideally, the ducks-a bit further inland. So not not a trench excavated in the Nevada wilderness?

When I asked Hainley about it, he felt pretty confident about the Purdy reference. And if we assume that holds, it’s possible that Purdy’s land has been subdivided and traded in ways that don’t map to the assessor records as they exist now.

Just turn left: what I think right now is the site of Sturtevant’s Heizer Double Negative, on the way to Heizer’s Double Negative [fire emoji]

What does map is Sturtevant’s note describing the site as the “first depression west of mwmwm ?” That matches to the coordinates she wrote. And that first depression is located at the turnoff for Double Negative. That exciting broad sited Heizer Double Negative on the way to Heizer’s Double Negative.

You remember the Dana Goodyear article, and the outrage Heizer still harbors toward Robert Smithson, the nerd from New Jersey who outtalked Heizer and stole his Land Art thunder with his stupid jetty? Can you just imagine the mayhem Sturtevant’s Double Negative would bring if, every. single. time. anyone went to see Double Negative, they were told, “Oh, just drive across the mesa till you see a Double Negative, then turn left and go a mile or so until you see another Double Negative“? Now that is power. And force. And she did it without lifting a shovel.

Hainley has next-level reads of Double Negative and House of Horrors, Sturtevant’s epic 2014 installation at the MAMAC in Paris which I’m still processing. But I asked, and he wasn’t quite sure, for obvious reasons, how many people knew about Heizer Double Negative and when. Was it a thing? Was it a timebomb, sitting in Sturtevant’s files, just waiting to go off, to upend the art historical apple cart, Duchamp’s Fountain-style? For the most part, Hainley said, folks who were around and in it in the 70s are a little hazy, and Sturtevant was always a little cagey. One person might know more, though, a lot more, and that’s the funder and longtime owner of Double Negative, and Sturtevant’s good friend, Virginia Dwan.