I wish I’d known about these before David Hudson posted one to wish Steve Reich a happy 88th birthday. Because I am transfixed.

In 1978, composer Steve Reich went to Oakland to make etching editions of two musical scores at Crown Point Press. He had planned to write an essay to accompany them, which would also be turned into an etching. There is not a point in my retelling this story when Reich’s own account, from an interview with Robin White, was published in 1978, in Vol. 1 of Crown Print’s journal View. Of course, it is available on the Internet Archive:

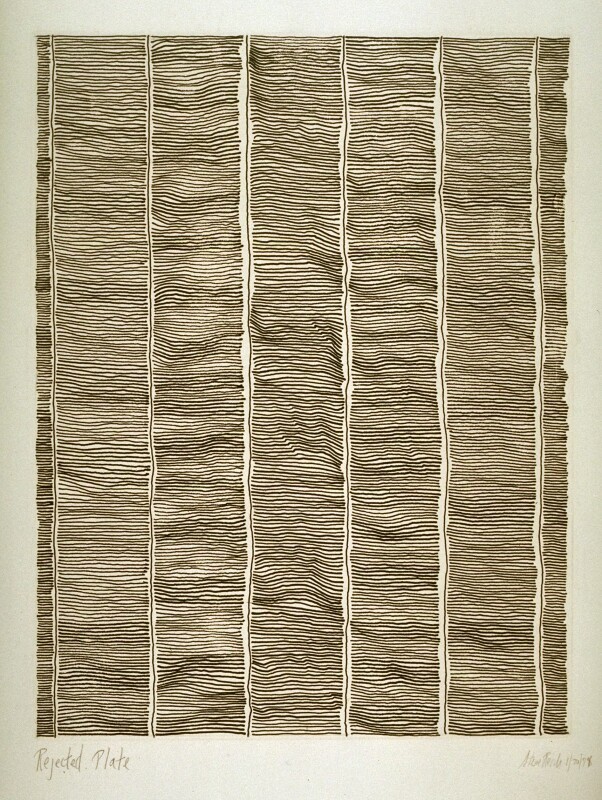

SR: I made some notes on the plane out to California. Before I went to Crown Point, I spent a week in Santa Barbara preparing some pieces with some local musicians and we performed them in concert. During that time I had a little time to try to work on the essay; it wasn’t coming along too easily. I arrived in Oakland, went down to the press the first day and spoke to Kathan [Brown, co-founder of CP] and the printers at the shop. I guess Doris Simmelink gave me some paper to write my essay on, back in my hotel room. I took the paper when she gave it to me—I looked at it—it had a familiar look and feel. It looked and felt like the paper on which I got my reject letters from the Guggenheim Foundation every year, a certain commercial brand of paper. I held it up to the light to see the watermark and sure enough, it was that paper—it had that watermark. I put it back in the bag and made a crack about another reject letter from the Guggenheim, and went back to the hotel room. I thought about the essay. I began doodling on the watermark. I laid the paper on the darkish imitation wood table in the hotel room and the watermark was quite clear. I had one of those 89-cent Pentel Roller Writer pens and I just began tracing the watermark itself—not with a rule, just using my hand.

RW: While you were thinking about what you were writing?

SR: While I was thinking about what I was going to write. But, by the time I got five or ten minutes into the tracing, I began to get interested in the process of doing it; I liked the way it looked and I liked…there’s a certain kind of repetitious, methodical action that I can get into that is a kind of exercise, like doing exercises in the morning. For me it was a physical act, very much marking on the sheet of paper, not really drawing anything. And when I had covered the entire sheet, I thought to myself this might, in fact, be better than the essay I had been working on. I wondered, “I’m not a visual artist, should I do this?” I spoke to Beryl [Korot, visual artist and Reich’s wife] on the phone, and she encouraged me to go ahead with it. I brought it in the next day and the printers and Kathan encouraged me to go ahead with it. And I went ahead with it, re-drawing it on paper laid over wax ground. There was also a second kind of paper which had a similar but somewhat different watermark, where there were many horizontal lines with a few vertical lines spaced considerably wider apart. It gave a quite different effect because my hand had to move further and the control I had over keeping it steady became even less, and therefore, the lines began to move even more. Of course, that movement became a real plus the more I did it.

Reich talks to White about the correspondences between this discovered artmaking process and his music. Both involve focusing attention on already extant patterns:

Steve Reich: What the women’s voices are doing in Drumming or what I’m doing in the drum section with my voice, is to simply pick out certain patterns that pre-exist; they are really there. The voice is used to sound like one of the instruments that is already playing, and to raise one of those patterns to the surface of the music so that you can hear it for a moment. And then at other times, two at a time are brought out as duets. It can get rather complex. so the visual equivalent of this is to simply show by underlining, or by drawing in more boldly, something which is in fact in the substance already. A watermark tracing is a literal equivalent of this because it’s reinforcing that which was already marked in the paper before I ever got it. By doing it freehand, without a ruler, the irregularities become interesting.

Also both are only possible because of the constraints the artist imposes on himself, a concept Reich developed via Stravinsky. And both derive their energy and beauty from the human variations and imperfections a machine couldn’t produce.

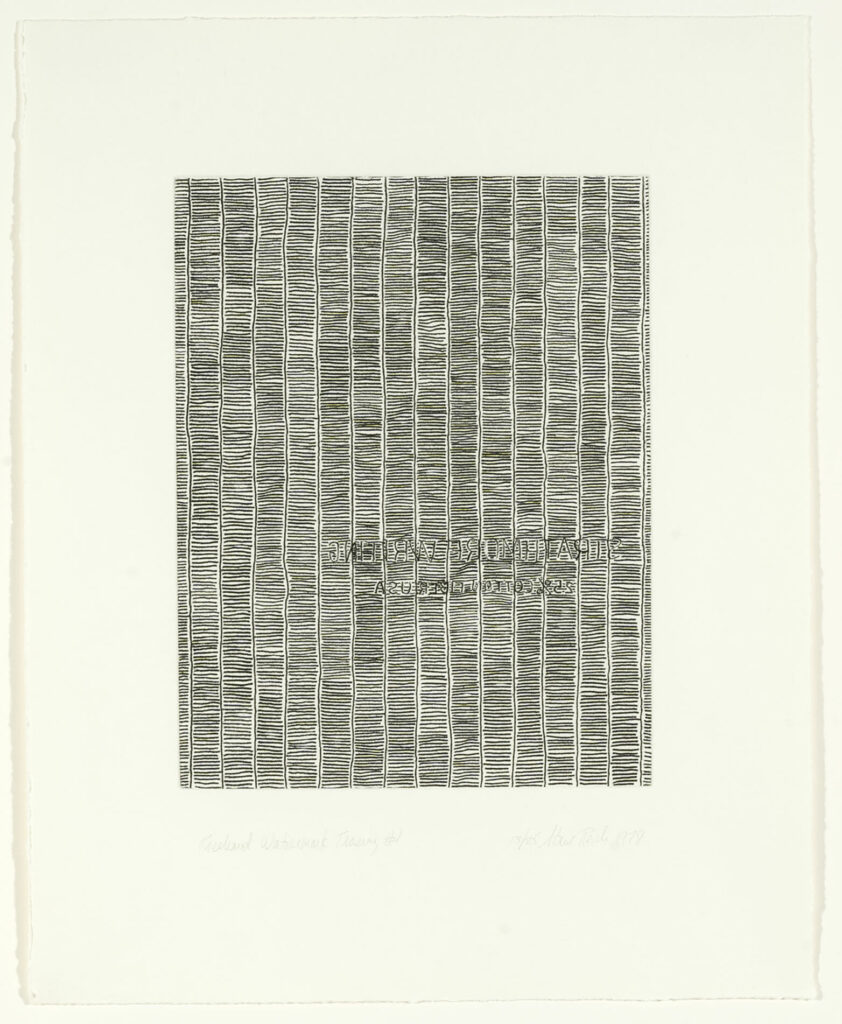

But not too much. In their Crown Point Press Archive the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco has a rejected plate from Reich’s Freehand Watermark Tracing. Apparently the tracing went a little too freehand. But that itself leads to the convergence, if not the emergence, of other, larger patterns.

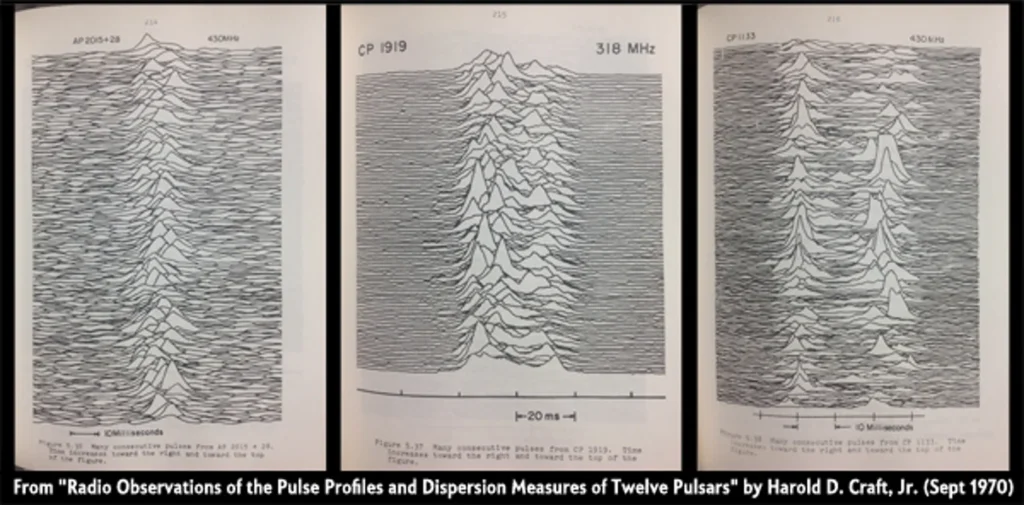

Scientific American art director Jen Christiansen’s 2015 search for the definitive origin of the most famous pulsar wave plot diagram in music history took him past his own publication to Cornell grad student Harold D. Craft, Jr. When Jocelyn Bell’s discovery of pulsars was announced, Craft was among a group of researchers at Arecibo Observatory, which happened to be the best instrument in the world for observing such phenomena, with the right computing power to process it:

…[T]he thought was, well let’s plot out a whole array of pulses, and see if we can see particular patterns in there. So that’s why, this one was the first I did – CP1919 [the first pulsar discovered by Bell]– and you can pick out patterns in there if you really work at it. But I think the answer is, there weren’t any that were real obvious anyway. I don’t really recall, but my bet is that the first one of these that I did, I didn’t bother to block out the stuff, and I found that it was just too confusing. So then, I wrote the program so that I would block out when a hill here was high enough, then the stuff behind it would stay hidden. And it was pretty easy to do from a computer perspective. I also wrote a program that, instead of having these lined up vertically like this, I tilted them off at a slight angle like that so that it would look like you were looking up a hillside – which was aesthetically interesting and pleasing, but on the other hand, it just confused the whole issue.

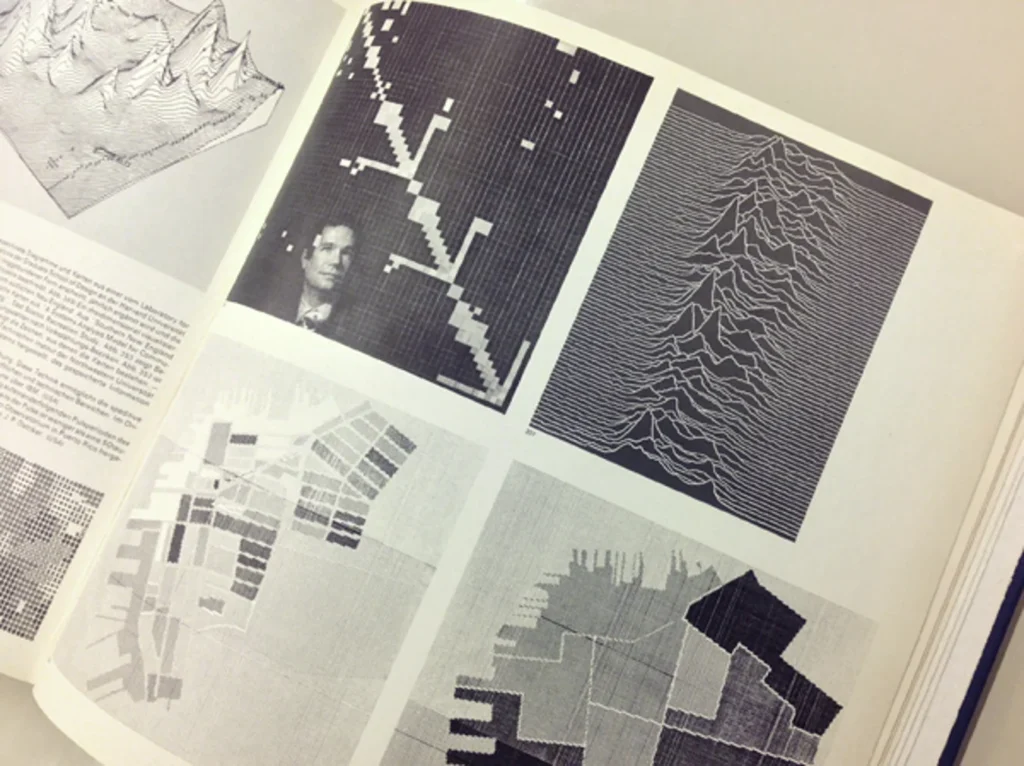

Though accounts vary about which Joy Division member brought Craft’s diagram to the attention of 22-yo Peter Saville, none could plausibly involve Reich or his Crown Point Press etchings. One of them said they saw the diagram when it was published, uncredited, in The Cambridge Encyclopaedia of Astronomy (1977). But as Christiansen noted, the diagram also appeared in 1974 in Graphis Diagrams: The Grapic Visualization of Abstract Data [credited to Arecibo Radio Observatory]. Unlike the Encyclopaedia‘s, but exactly like Saville’s, Graphis‘s version is inverted, white-on-black.

Like Bell, whose adviser won the Nobel for her discovery, Craft’s credit for the diagram went lost and unacknowledged for many years. In his conversation with Christiansen, he noted, “in the process of putting together the thesis, I would give this [diagram] to a woman draftsperson in the space sciences building at Cornell, and she would then trace this stuff with india ink, and make a much darker image of it, so that it could be printed basically.”

So the actual data image that ended up on Unknown Pleasures was originally traced by hand by an uncredited woman. Certain patterns pre-exist, and they are really there.

Steve Reich, Freehand Watermark Tracings Portfolio, 1978 [mmoca.org]

View, Vol. 1, 1978/79, Interviews by Robin White, Crown Point Press [archive.org]

Steve Reich [crownpoint]

Pop Culture Pulsar: Origin Story of Joy Division’s Unknown Pleasures Album Cover [scientificamerican]

Previously, Steve Reich-related: Glenn Ligon: Music and the Stenciled Word: I shall call him Mini-Lee