via Allison C. Meier comes a story I’ve missed for months by not reading The Art Newspaper over the holidays, and by not opening Swiss Institute emails. But in my defense, most people have been missing Gordon Matta-Clark’s Rosebush since its creation in 1972.

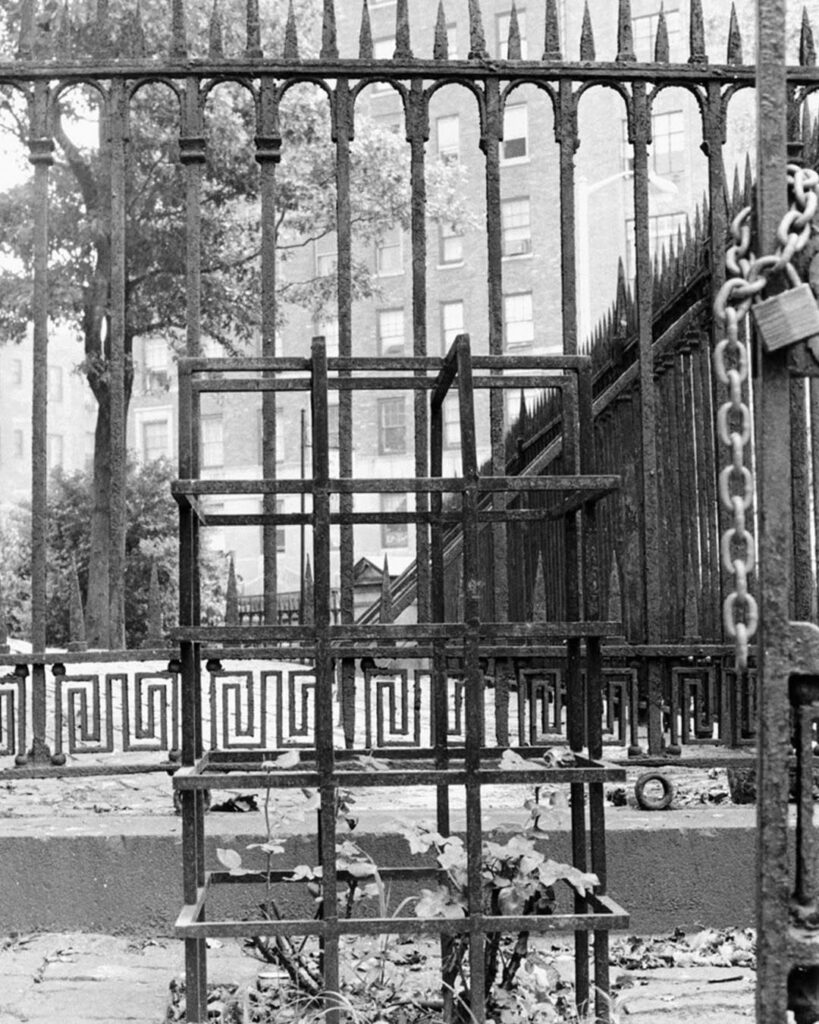

That’s when the artist planted a rosebush inside a small, gridded wrought iron cage at the entrance of St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery on East 10th Street in Manhattan. The work was “reactivated” last September as part of —or “alongside”—Energies, an exhibition at the Swiss Institute on artists collaborating with local communities and ecologies. The reactivation took the form of planting a new bush in the Spring, adding a plaque, and staging an afternoon of readings, music, and dance in collaboration with The Poetry Project and Danspace Project, both of which have long operated at the church.

How could Gordon Matta-Clark’s “only existent work in an outdoor, public space” be so lost for so long that it needed a double-dated (1972/2024) “reactivation”? Reactivation seems, in this case, to be a curatorial conceit to draw attention to the work in its community. But it also connects the rare, extant work’s physical reality with the estate, which seems oriented to handling documentation and the occasional collage or sketch.

For their part, curators knew. A vintage print of Rosebush from the artist’s archive was included in Philipp Kaiser and Miwon Kwon’s Ends of the Earth: Land Art to 1974 show at MOCA in 2012. [At least, it’s in the catalogue checklist, but not illustrated, and not on the show’s zombie website]. And it was in Life Between Buildings, a 2023 PS1 show about artists using vacant or interstitial spaces in the city in the 1970s. When Alanna Heiss founded PS1 in an empty school, incidentally. And when she tipped off Gordon Matta-Clark to the city’s surplus land auctions where he bought 15 weird slivers of land left over from the 20th century zoning process, which he turned into a project called Fake Estates.

Fake Estates seems relevant to Rosebush because it, too, was forgotten after Matta-Clark’s death, and the lots were repossessed by the city. In 2003 Cabinet Magazine tracked them all down—the artist’s documentation of each lot had been turned into a posthumous collage in 1992 [which]—and from 2005, a show co-curated with poet Frances Richard opened at White Columns and the Queens Museum. In that show, artist Valerie Hegarty’s sculpture Rosebush (For Gordon Matta-Clark) appeared to burst through White Columns’ concrete wall. Also because Richard seems to be the first to give Rosebush any significant critical attention, in her 2019 book, Gordon Matta-Clark: Physical Poetics.

She mentions the procession to the church to plant the rosebush, the later installation of the grid, and the work’s announcement in The Poetry Project’s monthly newsletter.

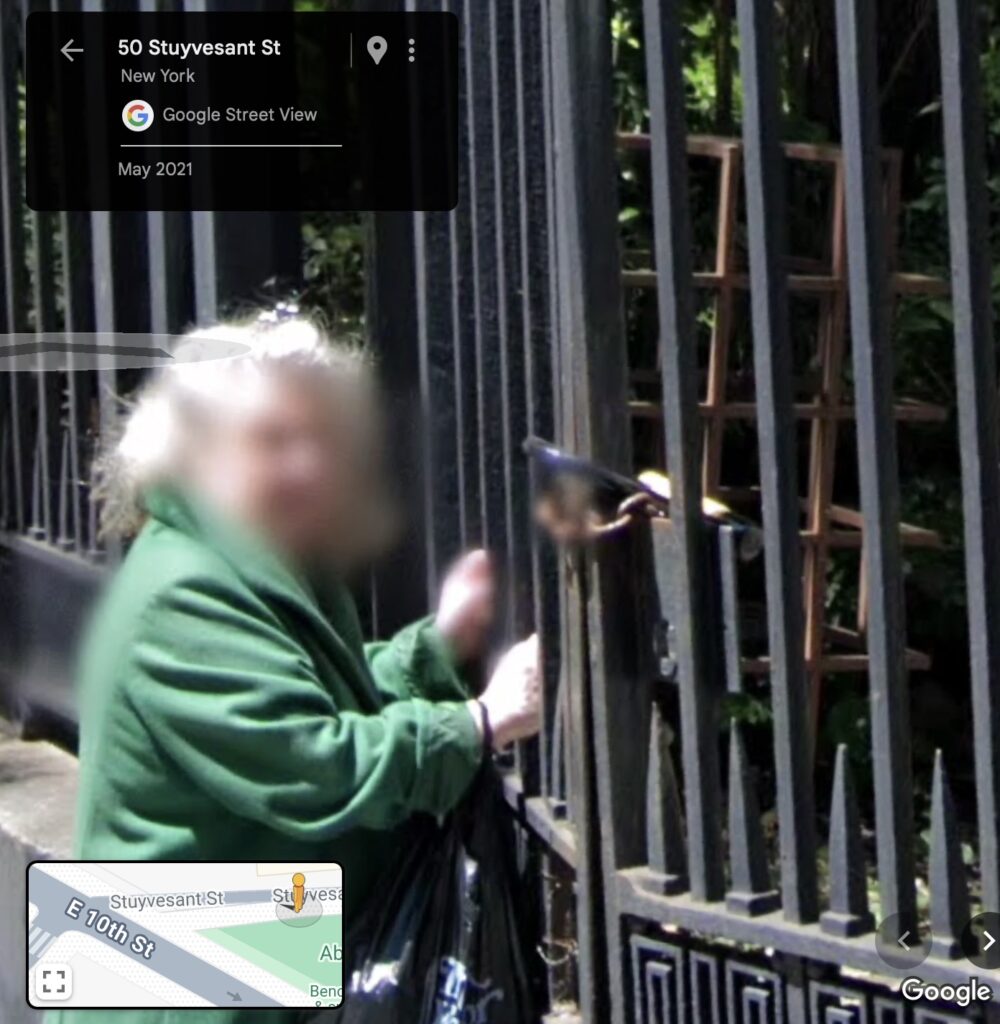

Meanwhile, it looks like St. Marks Church has done its stewardship duty by Rosebush. At least they didn’t throw it out. It was there in May 2021, when Google Streetview made its first pass along the pedestrian section of Stuyvesant Street in front of the church. It’s hard to say, but it does look like there’s some greenery inside it, too.

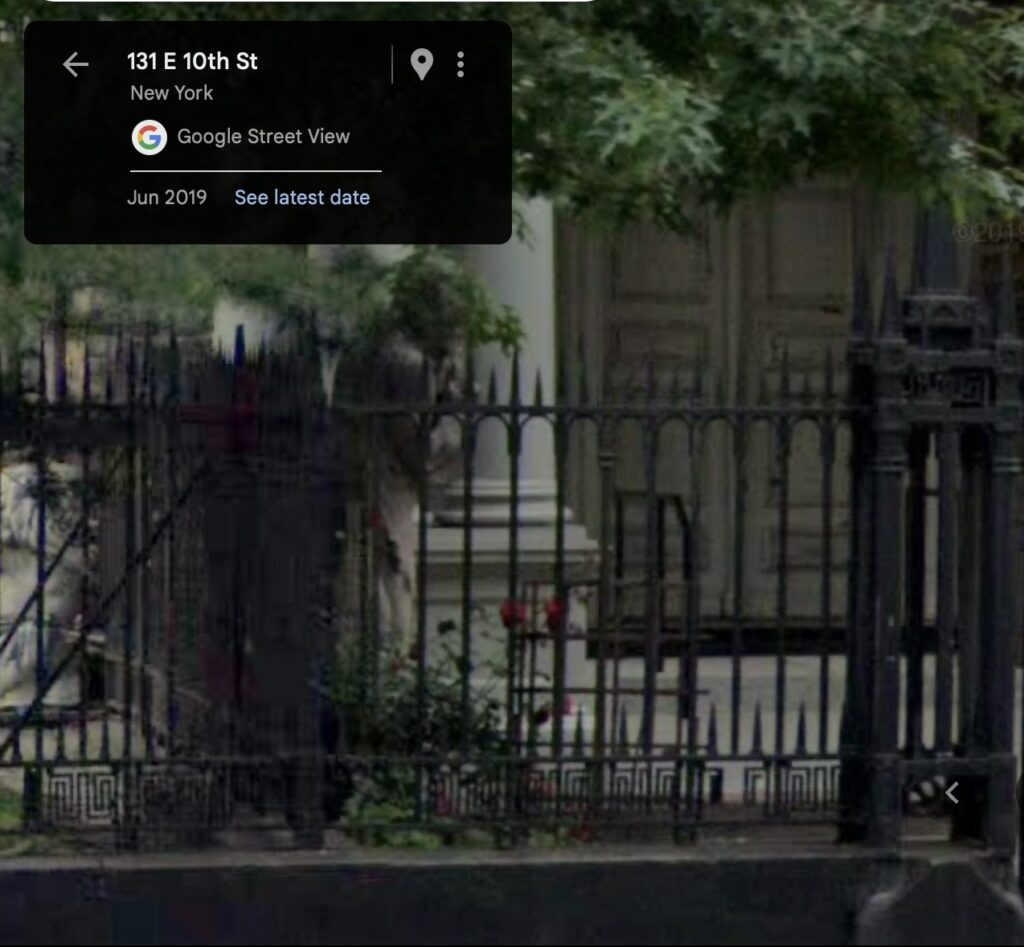

Indeed, there are roses blooming in Rosebush in GSV’s June 2019 capture.

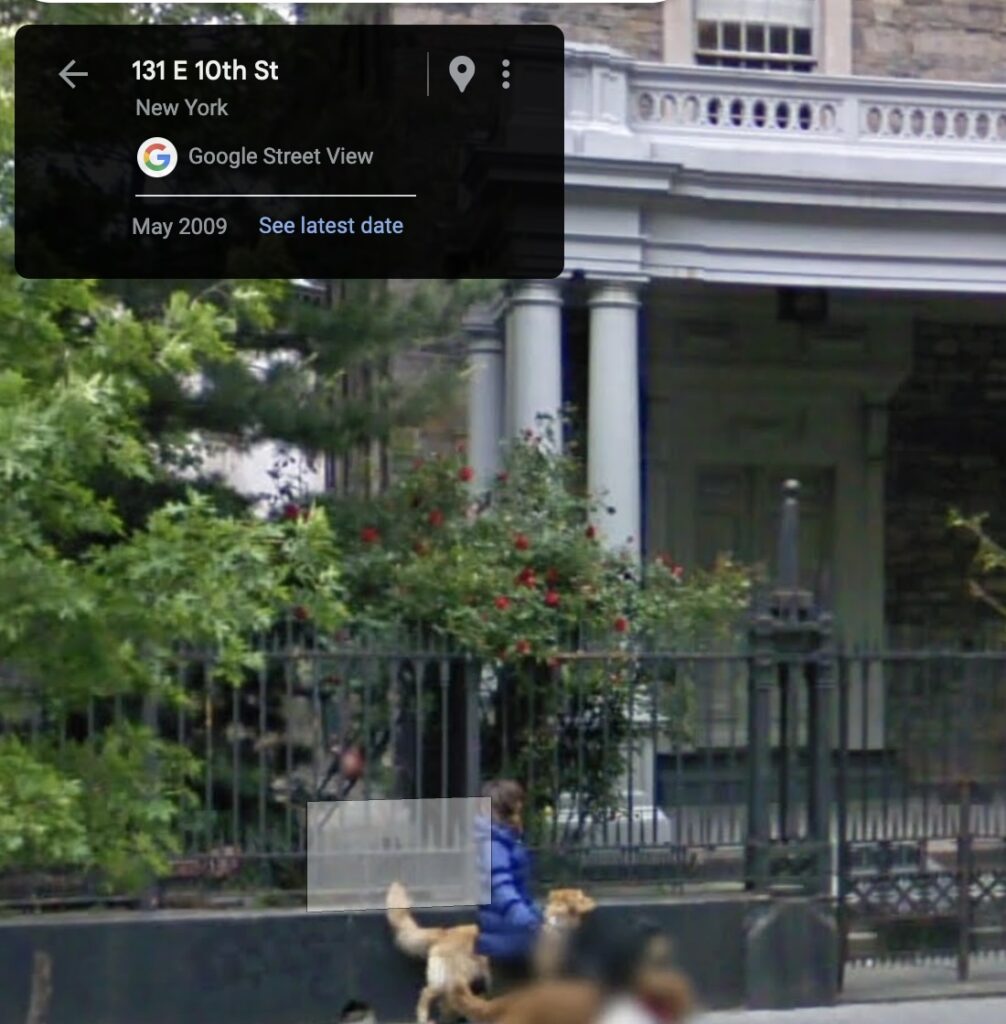

Going back as far as 2009, in fact, it looks like there’s a very healthy, mature rosebush on the site. What’s not quite so visible before 2017 is Rosebush, the grid. Had it been removed? Or was it subsumed by the overflowing rosebush? How long does it take a rosebush to get that big? 37 years? Was that Rosebush‘s original rosebush?

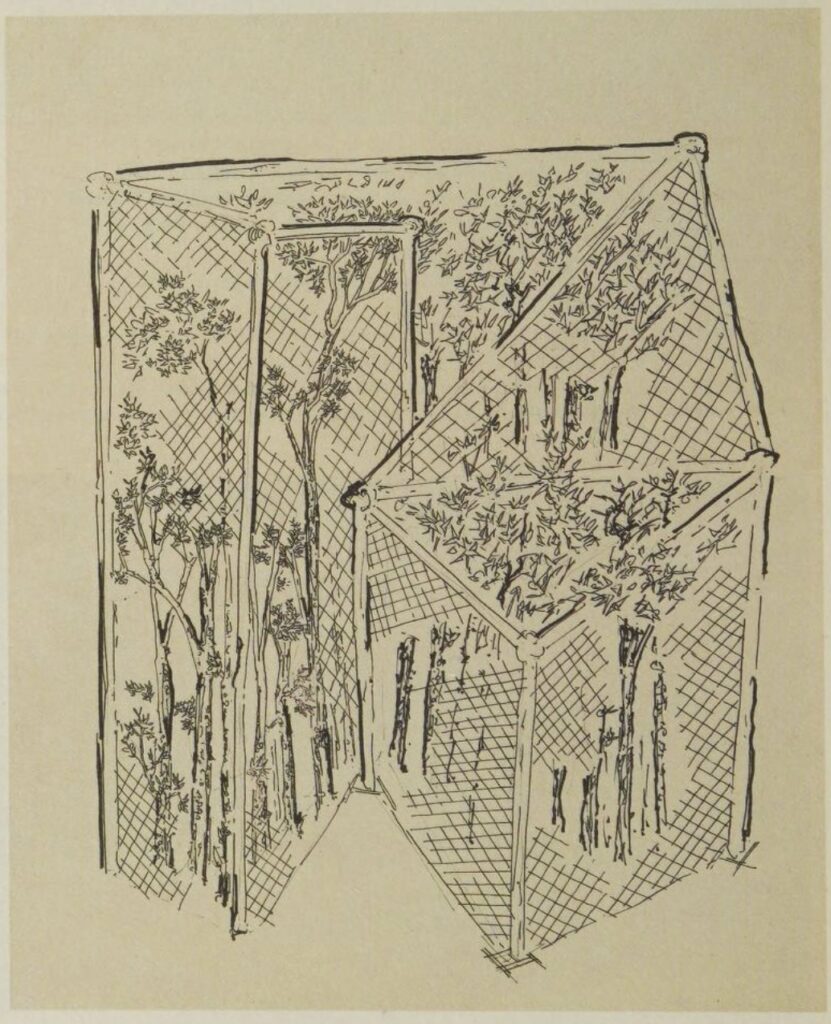

Richard quoted someone from St Mark’s saying that Matta-Clark “threatened” to make a six-story version of Rosebush in the wedge-shaped park that squared up the corner of 10th St & Second Avenue. Is that what the sketch, Untitled (Rosebush) (1972) depicts? That looks like a chain-link fence cocoon placed around and among full-grown trees, which makes me more aware of Rosebush‘s relationship to the churchyard’s wrought iron fence that surrounds it.

Matta-Clark’s interventions into the demolished or about-to-be-demolished environment were inevitably temporary, often leaving only fragments, images or films behind. Maybe Zwirner’s tried and found collectors only want ginned up photocollages, and museums don’t want to buy holes in their walls. But Matta-Clark’s entire body of work seems full of projects, performances, and installations both realized and not, which seem ripe for restaging. What if we call it a reactivation?

Gordon Matta-Clark’s caged rosebush, hidden in plain sight for 52 years, is marked and restored [theartnewspaper]

ENERGIES | REACTIVATION OF GORDON MATTA-CLARK’S ROSEBUSH AT ST. MARK’S CHURCH IN-THE-BOWERY [swissinstitute.net]