In one sense, you really don’t need any more info than what is in the photograph. What you see is what you see: 21 Pebbles, A to U. Yep, checks out.

@octavio-world highlighted the unfiltered finds of photos and objects posted to tumblr by the @metmuseum bot account, and this is definitely one of them.

The item listing at the Met identifies them as nephrite (jade), and provides the dimensions of each one. Somehow there is also another group of 21 pebbles, also jade. These are larger, and in addition to the very early group photo, each pebble is later photographed individually, in color. Turns out some are translucent, milky white with rust striations.

They were all acquired in 1902, from the same donor, Heber R. Bishop. Bishop was a NYC tycoon, an early Met trustee, and a voracious and encyclopedic collector of jade. When he died, he left the Met over 1,000 pieces of jade—including, let’s be real, 67 pebbles and one pebble fragment, but also a jade boulder officially logged as “Huge block of jade”—and the money to deal with it. Scrolling through The Bishop Collection by accession number tracks its three major categories: mineralogical, archeological, and art objects. Bishop collected jade from everywhere it could be found, and then from everywhere he could find people using it.

In 1909 the Met published a handbook/catalogue for The Heber R. Bishop Collection of jade and other hard stones, which explains the origin of the pebbles in the riverbeds of Khotan, in Turkmenistan, along with Burma, one of the major sources of Chinese jade. Three were given to “the Collection” by “Dr. Sven Hédin, the famous Swedish traveler.” The pebble fragment came from “a larger specimen found by the noted German traveler Hermann von Schlagintweit,” one of three brothers, Transkunlunians all, commissioned by the British East India Company to study the Earth’s magnetic fields in central Asian mountain territories it controlled in the mid-19th century.

Bishop only began collecting jade in 1878, when he saw and bought a large, intricately carved brush holder, exhibited as the “Heard Vase,” at Tiffany & Co. The Met’s 1909 handbook says this Artist’s Brush-Holder, No. 679, is from the Imperial Summer Palace.

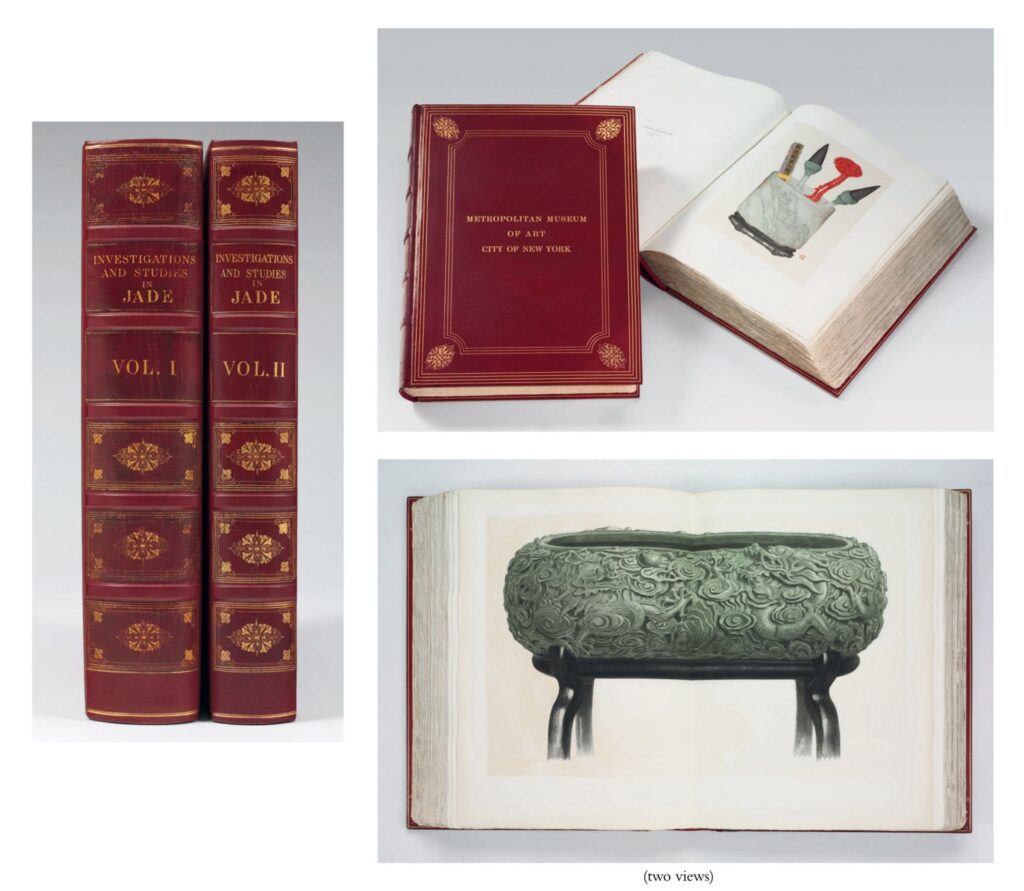

A more detailed backstory is available in The Bishop Collection (1906), a monumental, posthumous catalogue in two volumes, privately published in a lavish edition of 100, where it is reproduced in color as the frontispiece for (Vol. 1. [Though they’ve digitized neither, the Met must have gotten two copies of The Bishop Collection, because they sold ed. 2/100 in 2010. The Internet Archive scan was uploaded by the GIA, which acquired a copy in 2021.] Albert Heard, a Boston merchant, got the brush holder in Shanghai from an officer in the Anglo-French military force which looted and destroyed the Imperial Summer Palace in 1860.

After the first one, Bishop acquired dozens more objects “found” in the Summer Palace, which were turning up for sale in Europe. The Bishop Collection is forthright when something was “looted,” partly because it’s crucial to an imperial provenance. But also because everyone was doing it. From the entry for No. 689, a massive, 135 lb basin, carved with dragons and inscribed inside in the Qianlong Emperor’s own hand in 1774:

This unique object is the largest piece of finely carved jade known to exist. It was taken from the Summer Palace by the Chinese after its looting by the Anglo-French forces in 1860, being too heavy for the latter to take away with them. It is a well-known fact that Chinese plunderers were far more benefited by the looting than were the allied forces, as the latter took only precious jewels, metals, and other art objects easy of transportation.

Only. Bishop bought it in London, from a dealer who bought it from a Chinese dealer in Paris. In addition to the date, the Emperor’s inscription identifies the source and scale of the jade:

The colossal block was brought as a tributary offering from Khotan,

To be fashioned by skilful hands into a wéng-shaped bowl.…

Precious jade arrives from afar, as if it were a near production,

And comes in such large quantity that we feel really ashamed.

The Met, OTOH, does not. From the pebbles collected on the banks of a river in Khotan to the Emperor’s goldfish bowl, none of the jade objects in the Met’s Bishop Collection list any provenance before Heber R. Bishop.