Wait, the Warhol Museum called the 1-hour excerpt of Empire released on DVD an unauthorized bootleg?

Yes they did, in 2004:

“It’s a bootleg!” says Geralyn Huxley, a curator at the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh.

Which is odd. The Italian company Raro Video has released several Warhol films on DVD over the last couple of years. Andy Warhol: 4 Silent Movies is listed as a 2005 release on Amazon, and there’s a Chelsea Girls DVD, too.

Last year, Raro compiled 11 films and 8 discs into a box set, Andy Warhol Anthology, which–like all the films–is issued in region-free PAL format. There are extensive bilingual notes, interviews, and bonus material accompanying the discs, but there are also odd errors in formatting:

At least two of the silent films, Kiss and Blow Job, are mastered at the wrong speed [25fps instead of 16fps], and the once-randomly silent or audible soundtracks on the split-screen Chelsea Girls are provided in a single, seemingly arbitrary configuration which omits much well-documented dialogue

Despite these apparent errors, Raro insists that its films are authorized versions, not bootlegs, and that the errors were present in the master versions provided by the Warhol Foundation [which is distinct from the Warhol Museum].

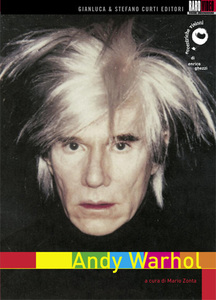

A film director, critic, historian, I-don’t-know-what named Mario Zonta is described as both the organizer of the Anthology and a “Member” of the Warhol Foundation. [Zonta, a longtime friend of Warhol entourage members/collaborators Joe Dallesandro and Paul Morrissey, also made a Morrissey documentary in 2002 which is included in Raro’s Dallesandro/Morrissey trilogy.]

According to an extensive discussion on Criterion Forum about public availability of Warhol’s films generally and the legal/definitive status of the Anthology specifically, Raro has long had VHS distribution rights to some Warhol titles and is merely updating the format.

After Warhol gave copies of all his film materials to MoMA in 1984, the Whitney Museum and MoMA have been jointly cataloging, restoring, and re-issuing Warhol films [for institutional use] under the Andy Warhol Film Project. From the Whitney description of the project, though, the existence of a traditional commercial “distribution” deal for Empire sounds very improbable:

In 1970, the artist withdrew his films from distribution; for the next twenty years, most critics and scholars could only reconstruct these works from reviews and other verbal accounts.

While it was screened soon after it was made in 1964, Empire was only shown in its restored entirety thirty years later, in 1994.

When asked in 2004 about the Raro DVD, Film Project director Callie Angell said Empire could not be cut. “It’s conceptually important that it’s eight hours long…Some people show it at the regular sound speed to make it go by faster, and I just think that’s not the film.”

And yet, in 2002, artist Donald Moffett put together a wonderful show called “Vapor” at Marianne Boesky Gallery, where he projected a 50-minute excerpt of Empire. I can’t remember now, but it feels like it was a single film reel of Empire on a loop, not a DVD. No one raised any objections to what seemed like excerpting for purely logistical, practical reasons.

And last spring, MoMA itself exhibited a 2h24m excerpt of Empire in the gallery of its theme show, “Out of Time: A Contemporary View” [the full 8:05 version was screened in the theater.] Here’s a description of what Empire‘s making and makeup:

Empire consists of one stationary shot of the Empire State Building taken from the forty-fourth floor of the Time-Life Building. Jonas Mekas served as cameraman. The shot was filmed from 8:06 p.m. to 2:42 a.m. on July 25-26, 1964. Empire consists of a number of one-hundred-foot rolls of film, each separated from the next by a flash of light. Each segment of film constitutes a piece of time. Warhol’s clear delineation of the individual segments of film can be likened to the serial repetition of images in his silkscreen paintings, which also acknowledge their process and materials.

At 40 frames/foot and 2:45 minutes/roll of shooting time over 7h36 minutes, that’d be at least 144 rolls of film. But according to the making of account on WarholStars.org, the Auricon camera they used was chosen because it had a 1200′ magazine, which cut way down on the number of changes required. Incidentally, Warhol almost never touched the camera during the entire 6.5-hour shoot. Instead, Gerard Malanga, Jonas Mekas, and John Palmer [who’s credited with the idea for Empire] ran the shoot while Warhol and several other folks watched.

Without having seen any of the DVD versions of the films yet, I would suspect that as a member of the Warhol orbit, someone like Mario Zonta would own–or have access to–period prints that predate MoMA’s involvement and the Foundation’s and the Museum’s creation.

Without having seen any of the DVD versions of the films yet, I would suspect that as a member of the Warhol orbit, someone like Mario Zonta would own–or have access to–period prints that predate MoMA’s involvement and the Foundation’s and the Museum’s creation.

And while those institutions may assert control over the intellectual property rights of the films, their claim would be contingent on Warhol’s and the films’ compliance with the copyright laws in effect when they were made. If a studio film like Stanley Donen’s Charade can inadvertently slip into the public domain for failing to meet copyright filing standards, I’d bet that most of Warhol’s films could easily be in the public domain, too.

The Warhol Foundation’s apparent involvement in the “bootleg” versions is made more interesting by their extremely controversial actions in authenticating Warhol’s work. On the Criterion forum, several people commented on the Foundation’s approach to the films as art, not “films” as a way to explain their distribution questions.

If the Foundation actually released or authorized error-laden versions of the films, it would be an utter failure of their responsibility to the authenticity of Warhol’s work. Many Factory regulars talked to Anthony Haden-Guest about the importance of Warhol’s films and their own experiences posing for the seminal Screen Tests:

Irving Blum says Warhol did not take his films lightly. ‘At the beginning he was far more revealing than he was post the shooting,’ Blum says. ‘If you had him alone, if he wasn’t performing, he was incredibly interesting to talk to. What he was doing was, in his terms, recapitulating all of cinema. Doing it single-handedly, starting from the beginning, and working in a parallel way to real cinema. It was nothing less than the most heroic task. And, as frivolous as some of the movies were, he thought of them very seriously.’

I’ve never heard of Warhol considering his films to be works, at least in the sense of editioning and selling them.

Just the opposite, in fact. As he explained in a 1966 interview for Cavalier magazine, he saw the films as distinct from his paintings and treated them as traditional, commercial films:

Cavalier: Do you want a lot of people to see your films?

Warhol: I don’t know. If they’re paying to see them. By the way, they can be rented. There’s a catalog, and the cost is nominal: one dollar per minute. A 30-minute film rents for $30. Sleep rents for $100, at a special rate. And you can get all eight hours of Empire for $120.

Cavalier: A lot of people have said that these are pretty boring films.

Warhol: They might be. I think the more recent ones with sound are much better.

But what if their very nature makes them the ultimate expression of Warhol’s pop, serial ideas? Why shouldn’t a period print of a Warhol film turn out to be as valuable and collectible as a Factory-produced silkscreen–assuming the Foundation doesn’t arbitrarily declare it “inauthentic,” of course?

Whatever the case, there are excruciatingly few ways to see Warhol’s films at all, and with no indication that MoMA or the Warhol Museum is planning to make definitive, commercial versions available to the public, a $145 PAL box set is about as good as it’s gonna get for a while.

A Controversy Over ‘Empire’ [nymag via kottke]

Buy Raro Video’s Andy Warhol Anthology on eight Region-0 PAL DVD’s, EUR99 now EUR63! [rarovideo.com]

Andy Warhol [criterionforum.org]

Factory Fresh [guardian.co.uk]

Previously: The Fake Andy Warhol Lectures