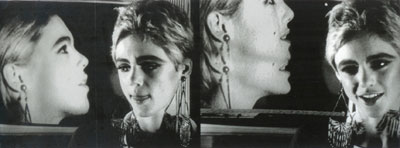

still from Inner and Outer Space, 1965

Fascinating. In 1965, months before pioneering video artist Nam Jun Paik got his hands on his own first video camera, Norelco loaned Andy Warhol its new, $3,950 slant scan video recording system for a month. [1] At the time, Sony, Ampex & others had just released the $1,000 VTR systems. Paik started using the Sony Video Rover Portapak almost as soon as it hit the market. Tape Recording magazine’s [!] interview with Warhol about the video system is included in Kenneth Goldsmith’s 2004 collection of Warhol interviews, I’ll Be Your Mirror.

While he had the camera, Warhol made Inner and Outer Space, an important, multiscreen portrait film of Edie Sedgwick where she sits in front of a video monitor that’s playing back a videotaped portrait of herself.

Here’s Callie Angell of the Warhol Film Project in a 2002 article for Millennium Film Journal:

During the month that Warhol had this video access, he shot approximately 11 half-hour tapes (at least, that’s how many Norelco videotapes have been found in the Warhol Video Collection). One of the interesting things about Outer and Inner Space is that it contains, in effect, the only retrievable footage from these 1965 videotapes. The Norelco system utilized an unusual video format, called “slant scan video,” which differed from the helical scan format [2] developed by Sony and other video companies, and which very quickly became obsolete. There are now no working slant scan tape players anywhere in the world, the other videotapes which Warhol shot in 1965 cannot be played back, and the only accessible footage from these early videos exists in this film, which Warhol, in effect, preserved by reshooting them in 16mm. [emphasis added]

What might be on the other nine Warhol tapes? From clues in the Tape Recording interview, they range from the Mel Gibsonian to the ur-video artistically Naumanian to the classically Warholian:

Warhol:…It’s the machine we’re going to use to do our 31-day movie.

TR: What?

Warhol: It’s the story of Christ.

…

TR: Have you recorded from a television set with the video recorder?

Warhol: Yes. This is so great. We’ve done it both direct and from the screen. Even the pictures from the screen are terrific. Soemone put his arm in front of the screen to change channels while we were taping and the effect was very dimensional…

…

TR:…Have you been trying to do things with tape that you can’t do with film?

Warhol: Yes. We like to take advantage of static. We sometimes stop the tape to get a second image coming through. As you turn off the tape it runs for several seconds and you get this static image. It’s weird. So fascinating.

…

TR: Is it that easy out-of-doors, too?

Warhol: Yes. We took the recorder onto our fire escape to shoot street scenes.

TR: What did you get?

Warhol: People looking at us.

As it’s being restored and re-seen, Andy Warhol’s early films are turning out to be central to his explorations of serial imagery, mechanical reproduction, celebrity, and portraiture, not a diversion from his “real” or “important” painting work. [For more discussion of this, check out Angell’s text for a 2001 exhibit of Inner and Outer Space at ZKM in Germany.]

This is not exactly new news, of course. [As David Hudson said in 2002, “the paintings are everywhere the films are nowhere.”] But I would say it’s also not reflected in the popular, i.e., market view of Warhol, precisely because the film works like Screen Tests can’t be collected and thus don’t command attention-getting auction prices.

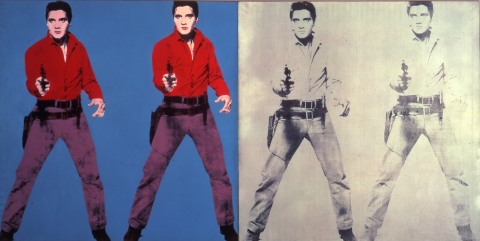

image: Holly, 1966 via christies

Imagine the treasure hunt if it were nine 1965 Warhol paintings known to be missing, extant but unseen. When video arcade hardware went obsolete, emulation software emerged to preserve the important part–the gameplay. Maybe some video gearhead or codec master somewhere will undertake the quixotic but art historically important mission of decoding slant-scan videotape and recovering these lost Warhol tapes.

[1] Hmm, another account of the Norelco loan describes the VTR as a prototype. And LabGuy’s timeline of Extinct VTR Formats doesn’t even mention a Norelco product until 1970.

[2] Hmm, according to this UBuffalo history of the videocassette, slant-scan and helical scan are the same thing.