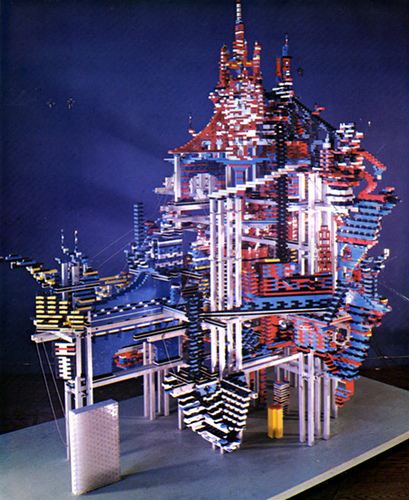

If you had to name one American, for instance, who clubbed together with a couple of friends in 1965 and spent more than three weeks building a futuristic seven-foot vertical city out of Lego, you might not immediately think of Norman Mailer. Thirty-three years later, however, the city still stands in Mailer’s living room in Brooklyn Heights, and its creator remains enthusiastic about his project. “It was very much opposed to Le Corbusier. I kept thinking of Mont-Saint-Michel,” he explains. “Each Lego brick represents an apartment. There’d be something like twelve thousand apartments. The philosophers would live at the top. The call girls would live in the white bricks, and the corporate executives would live in the black.” The cloud-level towers, apparently, would be linked by looping wires. “Once it was cabled up, those who were adventurous could slide down. It would be great fun to start the day off. Put Starbucks out of business.”

Last fall after he died, the fate of Norman Mailer’s Lego “City of The Future,” which stood in his living room for more than 40 years, was not publicly disclosed.

I wondered what it looked like. Turns out, it probably looks a lot like the photograph of it by Simeon C. Marshall, which accompanied The New Yorker article on Lego from which the above quote was taken.

update: Basically, awesome.

This photo was used on the cover of Mailer’s 1966 essay collection, “Cannibals and Christians.” The city itself was Mailer’s own proposal for dealing with the looming crisis of sub/urban sprawl: “If we are to avoid a megalopolis five hundred miles long, a city without shape or exit, a nightmare of ranch houses, highways, suburbs and industrial sludge,” he wrote in a 1964 essay in Architectural Forum, “then there is only one solution: the cities must climb, they must not spread, they must build up, not by increments, but by leaps, up and up, up to the heavens.” Thus, the Lego city. [quote via arcchicago]

In Mary Dearborn’s Mailer: A Biography, the construction of the Lego City is portrayed as nothing less than a bold attempt by the author “to make a revolution in the consciousness of our time”–if only they could’ve gotten it out of the writer’s living room:

In many ways this was a typically Mailerian project. He announced it in advance in the pages of the New York Times Magazine and, to underline his seriousness, in Architectural Forum. The prose city he outlined would change the face not only of public architecture but of society itself. He had long blamed architecture for many of the woes of contemporary society, and now he applied himself to setting forth his plans in pronouncements and, beginning in the fall of 1965, the creation of an actual model city, immense in scale and meticulously planned.

…

He decided to build a model of a city that could be populated by 4 million people, and to build it in his own living room. He conceived it as a monument to his sweeping utopian vision.

At the quotidian level, Norman acted as the brains behind the project, soon discovering that he didn’t like the sound of the plastic Lego pieces snapping together; it struck him as vaguely obscene. He delegated the task to [fourth wife] Beverly’s stepbrother, Charlie Brown, who worked as a kind of handyman for him, and to Eldred Mowery, a friend from Provincetown now in the city. The two men drove Norman’s 1961 blue convertible Falcon out to the Lego plant in New Jersey and returned with cases of the colored blocks. Then Norman directed them, instructing them to create hanging bridges, buildings with trapdoors, and four-foot-high towers, all constructed on an aluminum-covered piece of plywood on a four-by-eight-foot sheet of plywood supported by five-foot legs.

Construction proceeded apace, and Norman never really did call a halt to it. But someone from the Museum of Modern Art came out to Brooklyn to take photographs of the model, hoping to display it at the museum. At that point, Mailer and his helpers found that the “city” could not be taken out of the apartment. though they consulted movers with cranes and took measurements of the glass in the front windows, they soon saw that it couldn’t be removed without being disassembled first. Here Norman drew the line. He told Mowery to build a fence around it and leave it where it was. There it still sits, occupying a third of the living room’s floor space. Beverly, who contributed a scale model of the United Nations to indicate the overall scale of the city, professes that she loved it, but concedes, “It was a bitch to dust.”

That must be the UN in the lower left corner there. As so often happens to builders of utopian Cities of The Future, Eldred Mowery was arrested several months later in an art insurance scam. Seems that in December 1966, he and an artist/carpenter friend broke into the Provincetown cottage of painter Hans Hoffman and made off with 41 paintings, which they tried to return to the insurance company for a reward. Only instead of insurance company executives, they handed the works over to undercover FBI agents.

Any photos or documentation in MoMA’s archives remains to be explored.

The Joy of Bricks by Anthony Lane, Apr 2, 1998 [newyorker.com]

Apparently some brickers sussed out the photo last December, too[brothers-brick.com]

Mailer: A Biography, by Mary V. Dearborn [google books]

Buy Cannibals and Christians on AbeBooks [abebooks]