So I just got Odd Man In, Suzanne Muchnic’s 1998 bio of Norton Simon, and yeah, the Pasadena Art Museum was a mess, and Simon’s takeover of it was pretty stunning. But Muchnic portrays it as of a piece with Simon’s bold, intense dealmaking style. Fine.

And while much is made of Simon’s art churning, his passion comes through most clearly on the work of Edgar Degas. Odd Man In tells the gripping tale of Simon’s 1976 purchase of an entire set of 72 unique Degas bronzes, which had been forgotten and ignored in the foundry owner’s basement for over half a century. [Is this a commonly known story? Hmm, now that I mention it, I think I have seen Gary Arseneau’s extraordinary and incendiary condemnation of all Degas bronzes as fakes being foisted on an ignorant, taxpaying, museum-going public by a massive art world conspiracy before.]

Around 150 wax and plastiline figures–dancers, nudes, and horses–were found in Degas’ studio after his death. 74, plus that one with the tutu, were approved for casting. Two of those were lost. Degas’ heirs authorized 22 casts of each figure, made between 1919-1932, which included one complete set for the family, and one for Adrien Hebrard, the foundry owner. But there was another:

Degas’ waxes were too fragile to be used repeatedly to create an edition, so [master craftsman] Albino Palazzolo carefully made gelatine molds of the sculptures and used each mold to make one very fine wax cast. The wax casts in turn were used to produce the master set of bronze, or modèles. All subsequent casts were made from the modèles.

Although Degas’ modèles are marked as such, there are other ways to distinguish them from second-generation casts [i.e., the ones everyone knew until that point.] The modèles have more surface detail and evidence of the artist’s hand, and there is a difference in size: They are between 1.5 to 3 percent larger than later edditions, an effect of the contraction of metal during the casting process Degas’ modèles also have marks where gelatin molds were cut away, which can be seen under magnification, and traces of gelatin and clay can sometimes be found in the crevices of the sculptures and under the base.

You know, talk about the age of mechanical reproduction. This is where I have to marvel at the layers of translation and intermediation in making something like a bronze cast–and of their inevitable impact on what we see. I’ve looked at those Degas bronzes at the Met a hundred times, at least, without the slightest notion of this process or its implications. And I’ve toggled almost without thinking between Giacometti’s bronzes and a painted plaster original like, say, the one in the Menil. Anyway.

The modèles were immediately recognized as authentic; it turned out that they had actually been mentioned exactly once in print. Palazzolo discussed them in 1955 in an Art News interview, but after that, “the possibility of their existence had apparently been forgotten.”

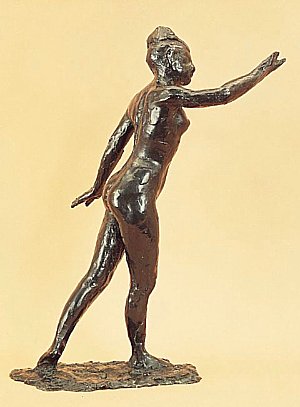

Grande Arabesque, First Time, No. 18 modèle, via nortonsimon.org]

The London dealer Martin Summers gave Simon first crack at the modèles for a price of $2 million. Summers wanted Simon to come to London to see the works, then as the dealer’s deadline approached, Simon called him at home before dawn and grilled him one last time:

“You have bronze No. 18?” Simon persisted, referring to a 19 1/4-inch-tall figure, Grande Arabesque, First Time, one of which he already owned.

“If you go to the airport now, you can catch the 8:15 flight to Los Angeles,” Simon said. “Bring No. 18 with you. I’ll meet you in the Polo Lounge at the Beverly Hills Hotel at 8 o’clock tonight.”

Grabbing his passport and packing the sculpture with a change of clothes in a carry-on bag, Summers headed toward the airport. His flight was delayed, but he reached the hotel only about five minutes late. He found Simon waiting with [curator Darryl] Isley. They were sitting in a booth with Simon’s No. 18 on the table. Simon ordered a round of drinks and guacamole, and got down to business.

When Summers lifted the statue out of his bag, Simon grabbed it and thrust his bronze at Summers. “They don’t even compare,” Simon said derisively, insisting his was better.

But he was only being contrary. When Summers called his bluff and said, “No, they don’t compare at all because yours is a fake,” Simon soon backed down. He could see that his own sculpture lacked detail that gave the modèle a far greater sense of life. Indeed, as he learned later, the figure he owned wasn’t even a second-generation cast. It was an unauthorized cast of a second-generation sculpture and thus of little or no value.

Needless to say, Simon bought the set, plus that ballerina with a tutu, which turned out not to be the modèle after all, but that’s a whole other story.

And of course, when they turned up in 1955, so they’re in the National Gallery. But that’s another story, too, and since my copy of Mellon’s memoir is in New York, it’ll have to wait.