As I have tried to make sense of the Cariou v. Prince decision, to figure out how Judge Batts found it so easy to dismiss Prince’s detailed explanation of his transformative ideas and process, I can come up with two possible rationales.

One is the distinction absolutely no one except Prince–Cariou, the judge all the lawyers, including Prince’s and Gagosian’s–makes between photographs and images, reproductions in a book. It’s one of Prince’s consistencies that reveals itself throughout his deposition and affidavit. [Always be selling!]

And it’s a point that Joy Garnett makes very cogently in her editorial in artnet which looks at the difference between mass produced images and fine art objects.

The very existence of Prince’s “Canal Zone” series is apparently now in peril, in part because no one seems to be able to tell the difference between a painting, which is a one-of-a-kind object, and a photograph, which is by definition mass-producible.

The other distortion I see is scale. Patrick Cariou and his lawyers prepared an exhibit [it’s in the book, $25 hardcover, $16 paperback!] detailing all the Yes Rasta images Prince used, in whole or in part, as source material in his paintings.

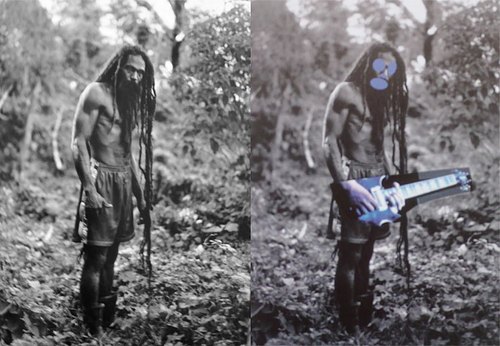

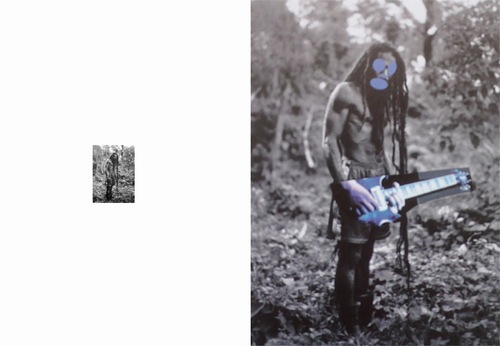

Photocopied side by side, the book pages and paintings can seem remarkably similar, even interchangeable. The comparison images that Cariou and friends released to the press are even more persuasive. But if this isn’t technically deceptive, it certainly obscures the scope of Prince’s transformations.

Cariou’s book is 10×12 inches. Prince’s paintings are 6-12 feet. Graduation, the painting made by altering the coloring of Cariou’s image, reprinting it, painting and collaging it, rescanning it, cropping it, inkjet printing it onto canvas, and then overpainting and collaging it again, is 5×6 feet. A more accurate side-by-side comparison would look like this:

These details of size, color, cropping, and format might seem like minutiae. But they are also exactly the kind of transformational changes cited by the judge in Blanch v. Koons. More importantly, they map directly to the decisions Cariou used to describe his own creative process–and they were also cited by the judge in declaring Cariou’s work “highly original.”

Maybe if the judge had compared object to object instead of image to image, she might have found Prince’s efforts a little more worthy of copyright consideration. In their filings, Prince and his lawyers repeatedly invited the judge to view the paintings themselves, either in Prince’s studio, or in a gallery or other space in town. It does not appear that this happened. But maybe she looked at Cariou’s exhibit, and figured she didn’t need to see anymore.