First, Happy Birthday, Mr. Richter.

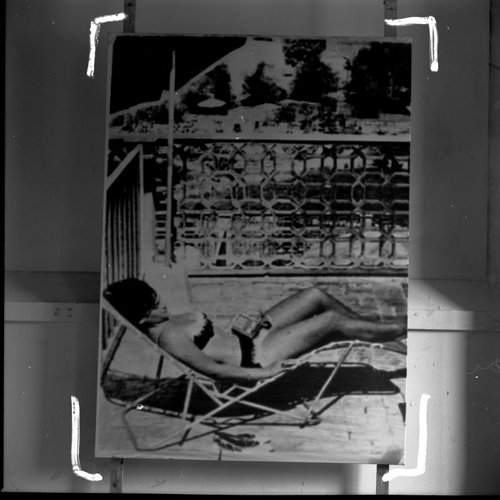

Destroyed 1964 Richter painting, image from Gerhard Richter Archkiv via Spiegel

I don’t know if Joerg knew at the time he first tweeted about it–he is plugged in and German, so who knows?–but I certainly had no idea when I picked up on the topic of Gerhard Richter “destroying” paintings by painting over them. But it turns out that the 74 paintings listed as “[DESTROYED]” on Richter’s website are only a fraction, barely half, of the paintings he’s actually destroyed so far.

In an interview with Ulrike Knöfel for Spiegel, Richter talks about the 60 or so photo-based paintings he destroyed in the 1960s during a very self-critical period of his career. Not to worry, though, because, being Gerhard Richter, he photographed them first

These photos, most of which were never published, are now either in the Gerhard Richter Archive in the eastern German city of Dresden, where the painter was born, or in a box in his studio in the western city of Cologne. They are testaments to his refusal to compromise.

Mhmm. Though the ambivalence/regret/equivocation Richter expresses in the interview reveal that a refusal to compromise is not automatically a win. Couldn’t he have just put them away and not looked at them for a while instead?

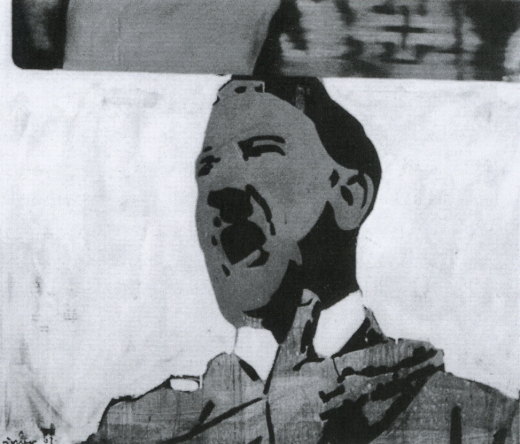

None were apparently included in Richter’s first catalogue raisonne, the source for his website’s “[DESTROYED]” list. And many appear to date from the earliest phase of his recognized work, 1962-4. Oh but wait, his much-discussed 1962 Hitler IS online, described as “believed to have been destroyed.”

Hitler, 1962, image via gerhard-richter.com

That seems like a new category, loaded with ambiguity. I like it much better than “[DESTROYED]” or even “Richter painted over this work in ___. The painting is now entitled ____.” Which, it turns out, has another example:

Today, Richter says he’s surprised at how many works he continued to destroy after the 1960s. Perhaps he will return to one motif or another, he adds, noting that “otherwise it would be a shame.” One painting, in particular, comes to mind. It was painted in 1990 and shows two young people standing in front of Madrid’s Museo del Prado, Spain’s national art museum. However, two years later, he painted over this work, turning “Prado, Madrid” into “Abstract Painting, 1992.”

Which, yeah, there is no Prado, Madrid in the CR, and there are at least 279 Abstraktes Bild done in 1992, so, this’ll take a bit of digging. I’ll update the post when/if I find it. [I’ll have to do an update post anyway, because I’ve already found at least two other overpainted paintings.]

This painting over thing is one thing. The other, which I’m kind of fascinated by now, is the relationship between painting and photography as it plays out in these destroyed paintings. Which, of course, still exist as the artist’s photographs. It’s like Barthes’ Camera Lucida; they’re gone, but not. I can’t tell if this is Spiegel’s interpretation or reportage:

Still, since his urge to destroy some of his paintings also made him feel uneasy, he photographed them before doing so.

But someone has to have already looked at this backup, insurance, documentary, archival, post-mortem, forensic, ghost aspect of the way these two mediums intertwine. Right?

Photo of destroyed Gerhard Richter painting, 1960s, by Gerhard Richter, image: Gerhard Richter Archiv Dresden via Spiegel

Meanwhile, the obvious thing–and isn’t that what I’m here to point out?–is to recreate these destroyed Richters. Whether you paint the archival photo, crop marks and background and all, in a meta-Richterian gesture, or just try your darnedest to bring their destroyed, painted subjects back to life, I’ll have to figure out. But paintings based on a painter’s photographs of paintings based on photographs? What’s not to love?

It’d be trivial to the point of meaninglessness to just print the Spiegel jpgs on canvas, or to order them up from Chinese paint mills. But I’d be interested to see just how much more meaning could be gleaned by painstakingly copying them by hand. Even if the answer is very little, that’s still an important datapoint.

His Own Harshest Critic | A New Look at Works Destroyed by Gerhard Richter [spiegel.de via bigthink]