Untitled (Still/Free), 1992/1994/2007/2011, installation shot at MoMA via Google Art Project

Seeing Rirkrit Tiravanija’s work Untitled (Free/Still) in MoMA’s Google Art Project space reminded me that I’ve been meaning to write about it for a while now. I revisited it a few of times after writing about Rirkrit’s awesome, blingy, highly collectable objects last fall. I ended by noting that as “MoMA’s acquisition of the 2007 redo of the 1992 curry piece betray, Rirkrit’s objects are often vestiges of the previous experiential pieces.”

Which remains largely true.

But I didn’t quite expect the objects in Untitled (Free/Still) to be such literal artifacts.

MoMA’s replication of 303 Gallery’s space in ply & stud didn’t bother me at all; it’s classic Rirkrit. And for a while, I didn’t mind the cases of ingredients stacked up around the installation; even though they felt a little like set dressing, they were also obviously part of the provisional space and the ad hoc dining experience.

Until I gave up my table one time to some older ladies, and moved over next to these boxes of coconut milk or whatever which–hello–have “Carnegie Museum of Art” written on them.

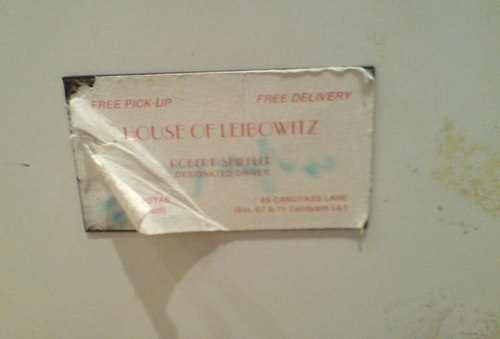

And then I head over to the beat-to-hell fridge and see Cary Leibowitz’s Candyass sticker for Bob Shiffler on the door. Shiffler, an Ohio-based collector, was the original buyer of Untitled (Free).

And sure enough, here are some registrar stickers from the Carnegie, which borrowed the piece, and there’s another shipping label, “11 of 14,” for “DZWIRNER,” who exhibited Untitled (Free) as Untitled (Still/Free) in 2007. So this fridge has been around, along with 13 other pieces or crates. An archival fridge.

So there was a certain explicit strategy to objecthood even at the formative beginning of Rirkrit’s most important practice. What’s going on here?

I finally asked MoMA curator Laura Hoptman, a friend from way back, who’s been working with Rirkrit even longer. She explained that Rirkrit identified certain elements, like the fridge and the rice cooker, as permanent parts of the work. And they would be joined by some of the remnants of its installation, incuding leftover ingredients, and even trash. Some of those elements have accreted at each installation of the work [this was the fourth], and MoMA would add something to it, too. They become part of the history of the piece.

Which, OK. But Hoptman also reminded me of the historical context–and by historical, I’m afraid I mean 1994, which I was around for–of Rirkrit’s work, and how almost desperately unsellable it was. And I guess I had forgotten that, that no, most collectors didn’t jump at the chance to buy installations, much less artists’ old appliances, in the mid-1990s. Even I kind of turned up my nose at the chance to buy a steamer full of old mussel shells back then, even though they were already in plexi! So the fact that Shiffler bought anything at all is sort of amazing.

Hoptman also spoke of Rirkrit’s Buddhism, and related it a bit to how he perceived objects, as well as the generosity of the experience his work fostered. But that only made me think of that fridge and the Dalai Lama, who talked about the problems of becoming too attached to his watch. We talked about how Rirkrit certainly has an awareness of the art object paradox inherent in selling his social/experiential work, and that the shift to chrome probably includes a level of critique, or caricature, even, of the desire for bright, shiny things.

I came away reassured, I guess, that I’m not wandering lost in my interpretation of Rirkrit’s work. But also kind of wary of how easily even our own histories and memories of art can be altered by the intervening present. Basically, because of the last decade-plus of market frenzy, I’d forgotten the 90s, when there was still a paradigm that art was being made for other reasons than to sell it.

Skip to content

the making of, by greg allen