Via the Hirshhorn via Art21 comes a nice two-way interview between Barbara Kruger and Richard Prince, originally published in BOMB Magazine in 1982, that ends:

RP I’m misinformed about style. I always thought it had to do with being able to wear the same kind of a jacket for ten years. I don’t know. What I wonder is . . . is it possible to have style and be unreasonable at the same time?

BK I think unreasonableness can mean any number of possible locations nearer or further away from the idea of reason. Because many of these positions are already coded, their shock value is tempered by style. A lot of times the idea of transgression really turns on a romantic conception of otherness; of a rebellion already tolerated. You know, the charming rogue, the picaresque cuteness of the bull in the china shop and in the art world, badness invades the atelier. Driving limos through heavy neighborhoods to look at the graffiti. Unstylish unreasonableness may be limited to the categories of the insane and the unpleasant (the poor, the unbeautiful, the unempowered). The non-romanticism of these kinds of otherness makes them unsightly and “vulgar” considerations for the polite company of international bohemia.

This image of limos driving “through heavy neighborhoods to look at the graffiti” is great in itself, but it also reminded me of an anecdote from, of all people, Jasper Johns.

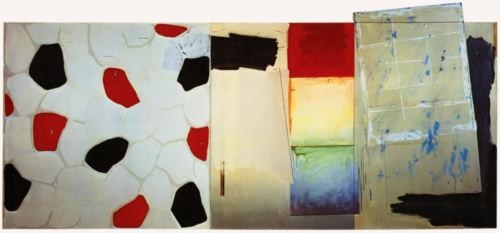

Jasper Johns, Harlem Light, 1967, image “taken. It’s not mine.”

It’s about the genesis of a motif that first appears in a 1967 painting, Harlem Light [above]. Here’s the version from Michael Crichton’s 1977 catalogue for Johns’ Whitney retrospective, which is still the most engrossing Johns book I’ve seen. And I’ve seen a lot:

Johns was taking a taxi to the airport, traveling through Harlem, when he passed a small store which had a wall painted to resemble flagstones. He decided it would appear in his next painting. Some weeks later when he began the painting, he asked David Whitney to find the flagstone wall, and photograph it. Whitney returned to say he could not find the wall anywhere. Johns himself then looked for the wall, driving back and forth across Harlem, searching for what he had briefly seen. He never found it, and finally had to conclude that it had been painted over or demolished. Thus he was obliged to re-create the flagstone wall from memory. This distressed him. “What I had hoped to do was an exact copy of the wall. It was red, black, and gray, but I’m sure that it didn’t look like what I did. But I did my best.”

Explaining further, he said: “Whatever I do seems artificial and false, to me. They–whoever painted the wall–had an idea; I doubt that whatever they did had to conform to anything except their own pleasure. I wanted to use that design. The trouble is that when you start to work, you can’t eliminate your own sophistication. If I could have traced it, I would have felt secure that I had it right. Because what’s interesting to e is the fact that it isn’t designed, but taken. It’s not mine.”

Crichton goes on to discuss the “small differences” that go unnoticed, and which are lost in creating from scratch. And of flagstones, like flags, an ideal Johnsian image,” which are found and known and abstract and concrete. Seriously, I could just keep quoting from that book all day.

But instead, I’m going to try to make sense of Kruger’s next sentence, “Unstylish unreasonableness may be limited to the categories of the insane and the unpleasant (the poor, the unbeautiful, the unempowered).”