I generally stay out of public arguments about MoMA. I feel too close, yet I’m not an insider. MoMA doesn’t need my apologia, and my firsthand experiences within the museum are not going to sway anyone. Everyone there is a grown-up who should be able to handle the responsibility for their decisions and actions.

Though I won’t see it until next week, I am fully prepared to be disappointed by the Bjork show. The museum went to an extraordinary effort on the show, to some very specific ends, that turned out to be the wrong ones. I would like to find out how things went wrong, and what can be done about it. I’m certain I’m not alone.

But Christian Viveros-Fauné’s artnet column yesterday, which purported to pull back the curtain on Klaus Biesenbach’s reign of curatorial terror at MoMA, is not going to help; it is not only poisonous and pointlessly personal, it’s inaccurate. I’ll give CVF the benefit of the doubt that his outrage skewed his interpretation of every rumor and anecdote, and that he’s not as reactionary or willfully ignorant as his errors make him seem. But it’s a non-credible non-starter for an actual discussion of MoMA’s situation.

Here’s a drive-by of some of the things that made me wince, and then a factcheck on what strikes me as a disqualifying error: the claim that Klaus ruined Marina Abramovic’s entire performance in The Artist Is Present.

First thing, shows are not created to please trustees. Some trustees, including the board president A. Conger Goodyear, demanded the cancelation of Lincoln Kirstein’s photomural show, the very first show in MoMA’s 53rd St building, because some of the artists criticized capitalism. In 1932. Some trustees flipped out over criticism of Nelson Rockefeller and the Vietnam war in Kynaston McShine’s Information show, which, along with other tumults, ultimately cost John Hightower his job as director [oral history pdf, a great read, btw]. Some groused about Bill Seitz’s trendchasing Op Art show, The Responsive Eye, too. Basically, trustee pleasure is a poor metric.

The Responsive Side-Eye, still from Brian DePalma’s short film, The Responsive Eye

Then this: “How, for example, does one begin to explain the institutional relevance of the band Kraftwerk’s eight-gig show” in 2012? The pedantic answer is by pointing to Barbara London’s three previous shows examining the intertwining history of art, music, and music video in the 80s. One could also wonder how one begins to explain the Hilton Kramerish cadence of a demand that “one begin to explain the institutional relevance” of something.

The problem with Tilda Swinton’s bed piece was not that it was “an unacknowledged rip-off [giant #*$%ing sic on that, obv] of conceptual artist Chris Burden’s four-decade old Bed Piece.” It’s that it was presented without the involvement or credit of Cornelia Parker, the artist who conceived the piece with Swinton in 1995.

Biesenbach’s “squiring” of “celebrities rather than artists or patrons”: Diana Widmaer-Picasso is a MoMA PS1 board member. Hedi Slimane and Miuccia Prada commission, collect, and collaborate with a ton of artists. Honestly, I’ve never understood the Kim Cattrall thing, but she’s a New Yorker like everyone else. Remember when Gina Gershon was always around Chelsea openings? Also, before Klaus, did anyone care who a curator was squiring on a red carpet? Highly doubt it.

I’ll be honest, I loved the account of Mykki Blanco’s poolside outburst at Klaus, even though the complaint that “he merely hobnobs with big-time names like ‘Mickalene Thomas’ and ‘Kehinde Wiley’ instead of supporting black artists” is even more LOLwut now than in Blanco’s original context. But it’s fine because do you remember who else wasn’t supporting black people that weekend, when the Eric Garner I Can’t Breathe non-indictment outrage roiled everywhere else? Everybody at Art Basel Miami. For each finger pointing at Klaus on this, there are three pointing right back at the white art establishment.

Now the claim that stopped me in my tracks:

As recounted by anonymous sources, Biesenbach interrupted Abramović’s precisely-timed 736-hour-and-30-minute marathon action in order to bask in some of the artist’s accumulated megawatt company. Scheduled to endure the performer’s gaze for a quarter of an hour, the curator lasted just eight minutes.

After vacating the chair, applause followed; but it was obvious from Abramović’s expression that something had gone wrong. The problem: Biesenbach had cut the performance short by throwing off its strict time signature. As relayed to artnet News, Abramović was livid.

This is where I want to pull Marina out from behind the movie poster to say, “I heard what you said. You know nothing of my work!”

First off, Where does this “precisely-timed 736-hour-and-30-minute” thing come from? At the time, The Artist Is Present was consistently referred to as a 700-hour artwork [love that url, btw]. But it was not even that. And there’s no way it could have been.

According to Abramovic’s log of her own time, as captured on MoMA’s The Artist Is Present sitter portrait set on flickr, she sat for 72 days: 61 7-hour days, and 11 Fridays, when The Modern stayed open 10 hours. Her total: 34,020 minutes, or 567 hours. It was physically impossible to reach 700 hours during museum hours, much less 736.5.

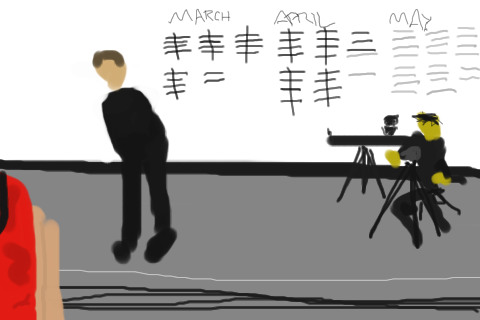

I extracted all the sitter data from MoMA’s flickr set and put it in a spreadsheet. And the total was 31,533 minutes, more than 41 hours less than Marina herself. Which would mean almost an accumulated week’s worth of her sitting by herself, with no one across from her. Some days her sitters would be down by more than an hour. Some days, though, they’d be over 420 minutes, as if they sat longer than Marina. Which you know did not happen. What it does mean is that friends & family and VIPs would come in to sit before or after the public.

via

On my day, Day 43, the first five people were already sitting or in line when the museum opened. [I expected not to pull any strings when I sat, but instead just wait. So I was a little surprised when I got to the atrium that there were strings to be pulled.] But check out Day 71 the Sunday before the project ended: Patti Smith, Michael Stipe, Marina collaborator Michel Laub. Sitters logged 438 minutes to Marina’s 420.

As it happens I watched the last hours of TAIP on the webcam and livetweeted it. [link updated 11/2022] Haha, and I wrote this at 4:57:

I know it looks like it ended early, but remember, she stayed late for the Barney/Bjorks. #italladdsup #abramovic

— gregorg (@gregorg) May 31, 2010

And indeed, The sitters on Day 58 logged 435 minutes to Marina’s 420. By Christian’s logic, by ending 8 minutes early, Klaus rescued Marina’s piece after Bjork, then Matthew Barney, and then Michael Stipe had thrown it off course.

Klaus Biesenbach sitting, May 31, 2010, 4:42pm via marinaabramovicwebcam

It is logical to question the precision of the flickr data. But these results and the ultimate time constraints of the show expose a fundamental difference between CVF and his anonymous source’s claims about Abramovic’s concept and how The Artist Is Present actually played out. And it was most definitely not performed in a way that could it could be made or broken in the last ten minutes by Klaus Biesenbach. No, Marina did that herself.

There are 4 cameras and two boom mikes on her. Something tells me the performance is continuing. #abramovic

— gregorg (@gregorg) May 31, 2010

When she stood up to take a bow surrounded by her labcoated performers and her several camera crews, and started working the frenzied ropeline like the ‘total stone cold diva’that she always was.

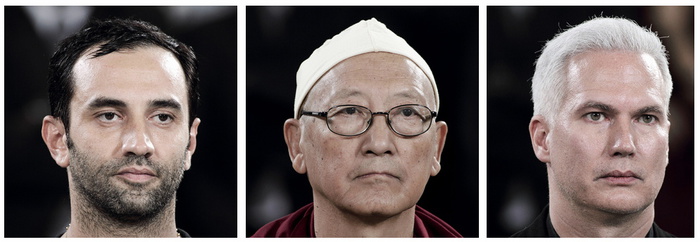

And then she turned up at the post-show gala in her custom Givenchy jacket sewn from the skins of 101 ethically killed snakes. [Givenchy designer Ricardo Tisci was the third to last sitter, btw, right before Abramovic’s spiritual advisor/lama Doboom Tulku Rinpoche, and Klaus. Let’s parse that.] It’s not about you, it’s about me, was the takeaway of the entire performance and the cultural whorl surrounding it.

Klaus and Marina, 4:51pm via marinaabramovicwebcam

In re-viewing the end of The Artist Is Present in light of CVF’s claim, I did notice something new, and different. When he got up, Klaus didn’t leave; he went over and gave Marina a hug while she was still sitting in her chair. The arranged finale meant that she was, for once, reliant on the presence of a sitter, her piece became contingent. And in the end, she didn’t end her performance, he did. The ready presence of her courtiers, guards and camera crew all point to a big diva finish. But did she plan a different ending that Klaus botched? Was he supposed to walk off and let her sit by herself until she was ready? In retrospect, it might have made for better theater, but I have no idea. More to the point, though: CVF and his anonymous source had no idea, either.

The job of a “Chief Curator At Large” is unusual, and so far, Klaus has been just the unusual guy to fill it. As CVF clumsily points out, Klaus has no staff, no department. I’d add that he has no collection to manage, and no dedicated exhibition space. It’s a different paradigm for curating, and it’s especially, even spectacularly different from The Modern’s traditional medium-based fiefdoms. During Glenn Lowry’s tenure, the museum has been making steady moves to open these silos, beginning with experiments like the MoMA2000 shows that closed the Cesar Pelli building. The PS1 affiliation and the spinoff of the Department of Performance and Media from the Department of Film & Video are other aspects of The Modern’s adaptation from the historical to the contemporary. Klaus was central to both those changes.

Klaus Biesenbach is not the future of MoMA, he is just the weirdest of many curators working to keep The Modern relevant in the 21st century. And the museum benefits from that weirdness. And more importantly, a museum that suits Christian Viveros-Faune’s reactionary, moralizing high-handedness would be a depressing, stagnant slide backwards.