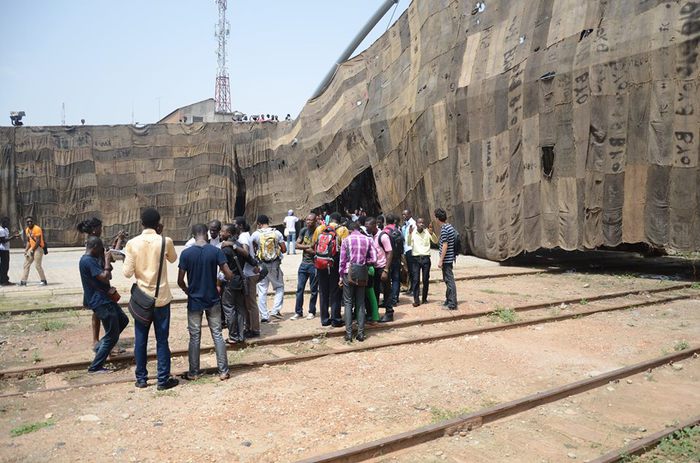

Ibrahim Mahama, installation KNUST, Summer 2014

[Ibrahim] Mahama is largely concerned with the way in which these materials are given meaning as commodities, as well as literally, as products of a given environment. The economic circulation of the jute sack is informed both by various transferences of value (from the container of commodities to a unique commodity by appropriation) and processes of exchange (from the official Cocoa Board to the quotidian lives of traders and consumers).

– curator Osei Bonsu [via Ellis King]

And it goes on from there. Ibrahim Mahama is a 28-year-old Ghanaian artist whose large-scale installation of repurposed jute sacks, stitched and draped, provides the overwhelming coda to All The World’s Futures, Okwui Enwezor’s exhibition at the 2015 Venice Biennale. He’s also been called “the next Oscar Murillo” by none other than Stefan Simchowitz, who claims he discovered the artist “on the Internet” and gave him his career. Now ArtNEWS is reporting that Mahama is being sued by Simchowitz and his dealer-partner Ellis King, for breaking their exclusive contract to represent him, and for “de-authenticating” nearly 300 [!] artworks he previously signed. The value of those artworks is now claimed to be nearly $4.5 million.

The complaint filed by Simchowitz in Central California Federal Court is eye-opening for its combination of candor, hubris, and delusion. [Here is a pdf, it’s only 17 pages, so read the whole thing.] The ArtNEWS article explains the circumstances of Simcho’s case very clearly, so read that, too. I don’t need to recap it.

Ibrahim Mahama’s 2013 installation at KNUST Museum, Ghana

What I find so extraordinary is Simcho’s claims at having made Mahama’s career and his audacious manipulation of Mahama’s work. Let’s look at the first one first:

8. Prior to meeting Simchowitz, Mahama had little, if any, recognition in the Western art world. Mahama had never displayed his work in any gallery or exhibit outside Ghana, either individually or as part of a group. He had made few sales of his work, if any. His work was not included in the collections of any museums, and exhibitions of his work were limited to Ghana. In short, Mahama was virtually unknown to the art world and had no experience exhibiting his art outside of his home country.

9. In or about 2012, Simchowitz contacted Mahama through Facebook. Simchowitz had seen photographs of some of Mahama’s pieces online, principally consisting of draped jute coal sacks, and thought that he showed promise. Simchowitz eventually introduced Mahama to Ellis King, and the parties agreed to work together.

The timing here is not trivial, and Simcho’s 2012 claim is vague at best. But in late 2012 Mahama showed one of his first jute sack installations during his MFA show at KNUST, El Anatsui’s alma mater and the leading art school at the top university in Ghana. That’s where artist/filmmaker/curator Nana Oforiatta Ayim scouted him out and began collaborating with him, introducing him to her international network. As Ayim put it:

I agreed to collaborate with him, connected him with collectors, wrote about him to institutions like the Tate and the Saatchi, to provide him a bridge at that early stage of his career. The art world, like so many others, is so full of corridors and gatekeepers that an artist, especially one working and living in Ghana, could go their whole lives without ever being able to sustain themselves through their work. I am a little weary of institutionalising this kind of ‘residency’ as I’m not keen on that particular play of power and never have been, the thought of myself as a purveyor whose word ‘makes or breaks’ an artist is a little sickening, as I don’t adhere to that notion of privilege. And yet, there is no denying that an email here, a phone call there, from someone who has already built a reputation through their work, can enable an artist like Ibrahim to have his art seen in galleries and museums internationally, enable him to have a residency in London, to sell and provide himself an income, to stay living in Ghana rather than moving abroad, to not compromise on his vision.

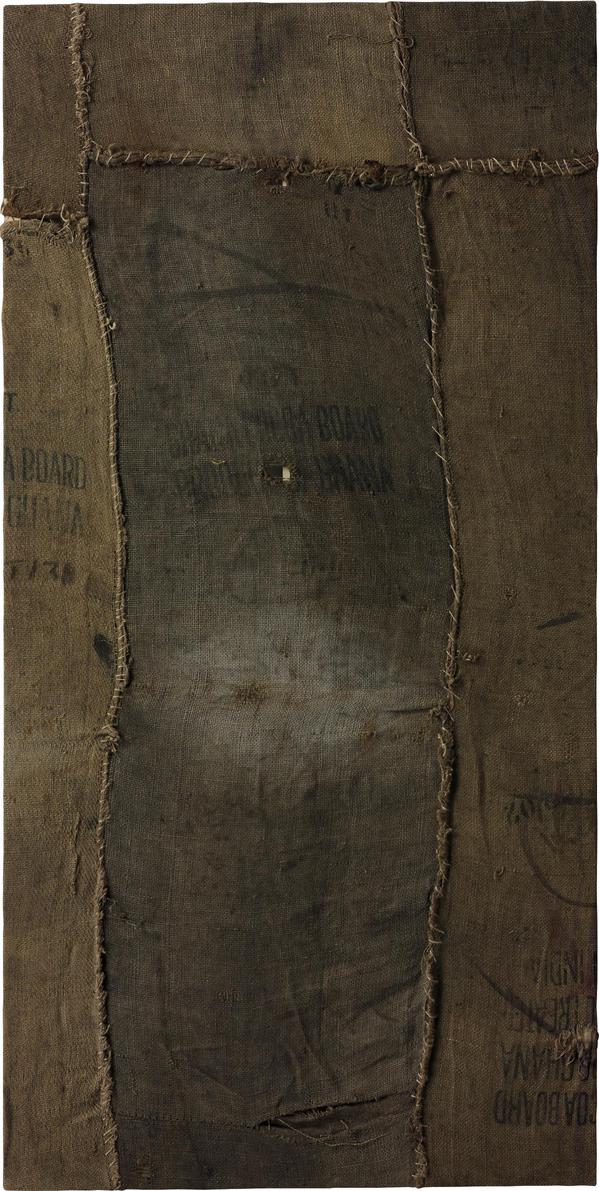

And that is almost exactly what happened. In 2013 Mahama had a residency in London at Gasworks; created a jute sack installation at the Saatchi Gallery [and another in 2014]; and, according to the lawsuit, in October 2013 he agreed to sell Simcho & King six “Lots” of sewn jute sacks for £90,000. Two Lots, Simcho claimed, totaling about 5,000 sf, would be for two installations in King’s Dublin gallery. In 2014 the other four “Lots” [which I estimate to have been 8-9,000 sf total] went to London where they were cut up and stretched to make 309 separate, painting-lookin’ artworks in three different sizes [9×4.5′, 8×4′ and 6×3′].

Which would turn out to give the young Mahama a new perspective on commodity, appropriation, and the process of exchange. Simcho’s suit says the “Contract” with Mahama was oral, yet there is obviously email traffic that flowed throughout the relationship. Mahama, the suit says, visited Simcho’s guy in London “to oversee and approve the stretching process.” Months later, in Dec. 2014, Mahama went to Dublin where he installed King’s show, and where he “signed the 294 Individual Works.”

“As a result [of the Dublin show in January 2015], the formerly unknown Mahama suddenly rose to fame,” claims Simchowitz. This, after two shows at Saatchi, a London residency, participation in DAK’ART, the largest African biennial, and an announced show at The Mistake Room in Los Angeles, and certainly after the decision to be in Enwezor’s Biennale [though two months before the public announcement]? No. Simchowitz did not make Mahama famous. He tried to buy big into momentum surrounding a clearly ambitious, talented, young–and recognized–emerging artist.

And then he sold big right ahead of the Biennale announcement. Simchowitz says he made Mahama’s career, and made him famous, but the collectors he flipped to didn’t even know who “the next Oscar Murillo” was they were buying: “I’ve sold Ibrahim’s work to ten of my best collectors without telling them what they will be getting,” Simcho told Los Angeles magazine, “I called it the Simchowitz Trust-Me Special.”

Lot 107: Ibrahim Mahama, Untitled, 2014, “Signed and dated ‘Ibrahim 2014’ on the reverse.” It already found its way from Simcho to secondary market dealer Inigo Philbrick, who cashed it out for £12,500 in June 2015. image:phillips

What would Mahama call it? Despite having sold the material and signing them, the artist clearly had second thoughts about the 300 stretched works, and about continuing with Simchowitz and King. Another important exploration of capital, commodification, exchange, and colonialism, I guess. During the Dublin show the artist cut ties, asserted that the 300+ works were no longer authentic, and claimed control and copyright over the installations.

The suit says 27 stretched works were sold for around $16,000 each. That’s almost $450,000, at least double the dealers’ entire outlay. The lawsuit is over the impending worthlessness of the remaining 282 stretched works, which comes to $4.45 million. Plus expenses. Simcho can’t claim he lost money on Mahama; only that he hasn’t made enough. And enough here means at least a 20x return.

So WTF. The copyright thing is a non-starter. The only way Simcho can claim copyright on artworks is if he claims he made them, in which case, they’re even less than worthless, or he documents they were work-for-hire, which who even ever? The biggest issue of the lawsuit is whether it’s even valid. Does Mahama selling entirely other work directly to an unidentified California collector give the court enough reason to examine events that transpired between parties in Ghana, London & Dublin? Lawyers can tackle that one.

It all leaves the question of the stretched artworks. Which, though he regrets it, Mahama was apparently involved in making. And signing. Part of me says, so what? Richter signs stuff that’s not art. He excludes stuff that he’s made and sold. Is an artist bound for life by every creative decision he makes at 26? That’s the risk of buying early work from emerging artists. It might be famous someday, it might be worthless. Simcho’s real problem is that he had 300 pieces of it. He tried to buy it all. He bought all the guy’s materials in bulk, then he chopped them up. He turned installations into paintings. Not paintings in the art sense, but as a unit of exchange: painting like breaking a hundred into singles so it goes farther at the club.

Ibrahim Mahama, Adum Train Station installation, 2013, image via: publicdelivery

There is one subset of 15 unsigned works which might show Mahama the way out of this dispute. Simcho calls them “the California Works,” because he has them:

Each of the unsigned pieces was created at the same time, in the same place, by the same person (Atkins), in the same manner, from the same materials, and for the same cost to Plaintiffs as the works Mahama did sign. On information and belief, Mahama did not provide any reason why he failed to sign the California Works.

59. Bearing Mahama’s signature to verify their authenticity and provenance, the California Works may be sold for approximately $16,700 each. Without his signature, the pieces are simply jute coal sacks mounted to wooden frames, which impacts their commercial value.

He says “Simply jute coal sacks mounted to wooden frames” like it’s a bad thing. Yet the transactional history, the embedded memory and experience, and the transformation of those jute sacks is at the core of Mahama’s practice. What if he just kept on making them, as an infinite edition? Instead of de-authenticating Simcho’s 300 Mahama pseudo-artworks, why not just devalue them, by making as many as anyone in the world wants?

Mahama employs the traders who provide him the bags to sew them. Usually they are undocumented migrant workers. So a big jute sack artwork export business would create jobs in Ghana. image: gasworks

Mahama could continue his jute sack acquisition process, and keep hiring his undocumented migrant merchant workers to sew them. And then he could sell these entry-level Mahamas for what Simcho paid: about $300, stretched. Make as many as the demand warrants, whatever the market will bear. It’d be like Olafur Eliasson’s Little Sun solar lamp artwork, but in reverse. Like Danh Vo’s father’s calligraphy letters. Or Walter de Maria’s infinite edition High Energy Units. Who says art has to be expensive, or that the white guy collector’s the only one who can reap the profits from selling it? With Mahama’s Stretched Art, Ghana can diversify from cocoa and develop an export market for the detritus of consumer capitalism transfigured into tasteful masstige commodities of criticality. Catch the vision!

Jute Sack Artworks Are at the Center of Simchowitz Lawsuit Against Venice Biennale Artist [artnews]

Ibrahim Mahama talks with curator Osei Bonsu in Oct. 2014 at the Contemporary African Art Fair in London [youtube]

UPDATE: SIMCOR CEO responds on Facebook [facebook]