UPDATE/CORRECTIONS

One benefit of MoMA’s historically grounded exhibition of The Migration Series is a broader look at Jacob Lawrence’s work and the context in which he made it. Which includes floating this picture to the surface: Lawrence and fellow sailors posing with one of the paintings he made while serving in the US Coast Guard during WWII. [via @rebeccaonion and @thebenstreet]

There sure is a lot going on in that photo, and given the racial segregation and discrimination that still held sway in the US military during WWII, it feels frankly fake. But there it is. And it turns out Lawrence served on the USS Sea Cloud (IX-99), the first integrated ship in the Navy (and Coast Guard, obv) since the Civil War. IX-99 had once been the world’s largest private yacht, the Hussar, and was designed by & built for Marjorie Merriweather Post and her husband EF Hutton, and later rechristened the Sea Cloud when Post married Joseph Davies. [The Sea Cloud is still in service as a crazy-luxe, old-school masted cruise ship, and every yacht-flaunting collector who hasn’t ridden this thing up the Grand Canal for the Biennale should hang his head in rubber dinghy shame.]

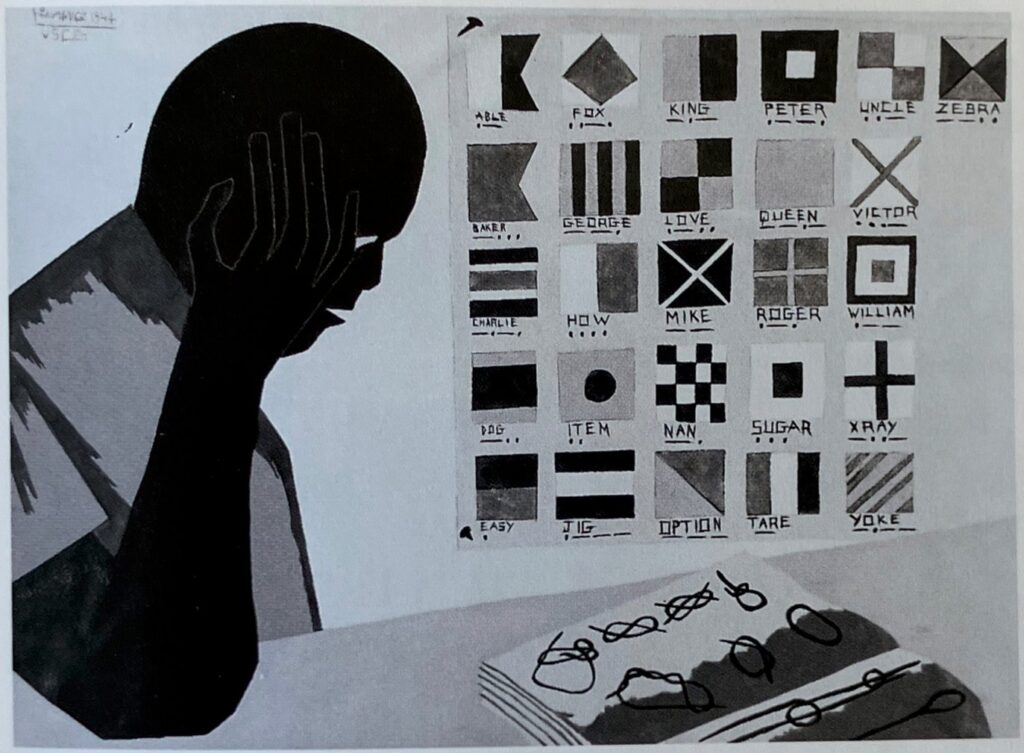

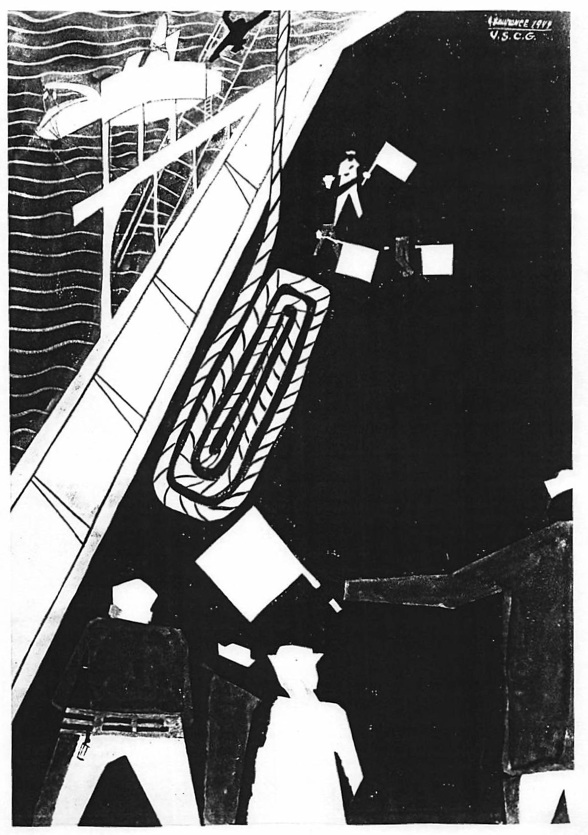

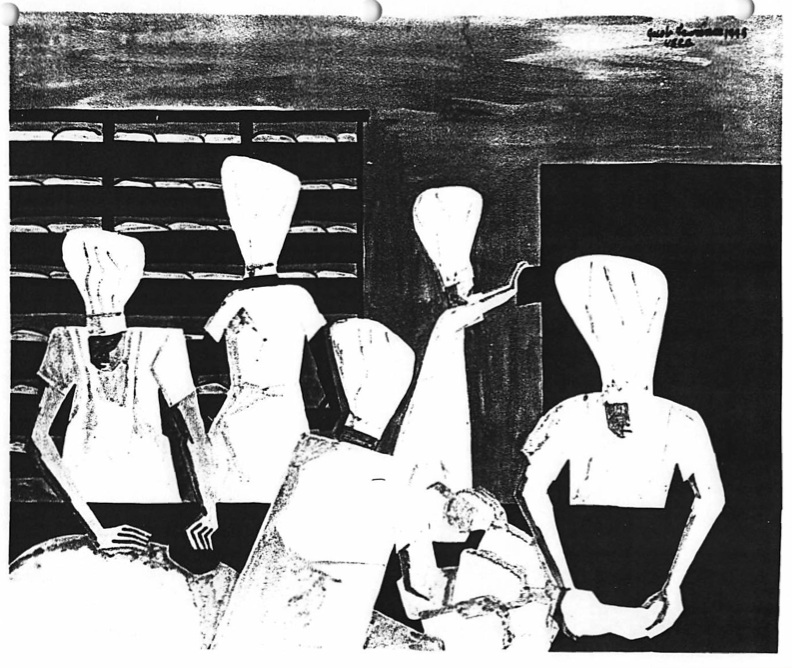

Well, OK, this one’s not lost: Embarkation or possibly Landing Craft, gouache and watercolor on board, Collection USCG Museum

Lawrence was already well-known as an artist when he was drafted in 1943, and his commanding officers recognized this, and made painting part of his official duties, first as a public relations specialist on the Sea Cloud, and then as a combat artist on the USS Gen. Richardson. Lawrence returned to civilian life in late 1945. His War Series paintings, created on a Guggenheim grant in 1946-7, are in the Whitney collection, and are on view right now on the 7th floor. But almost all the paintings he made during the war itself are missing.

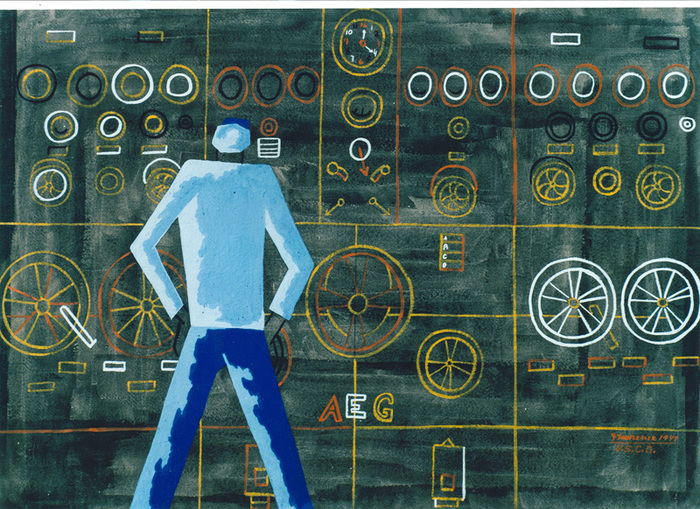

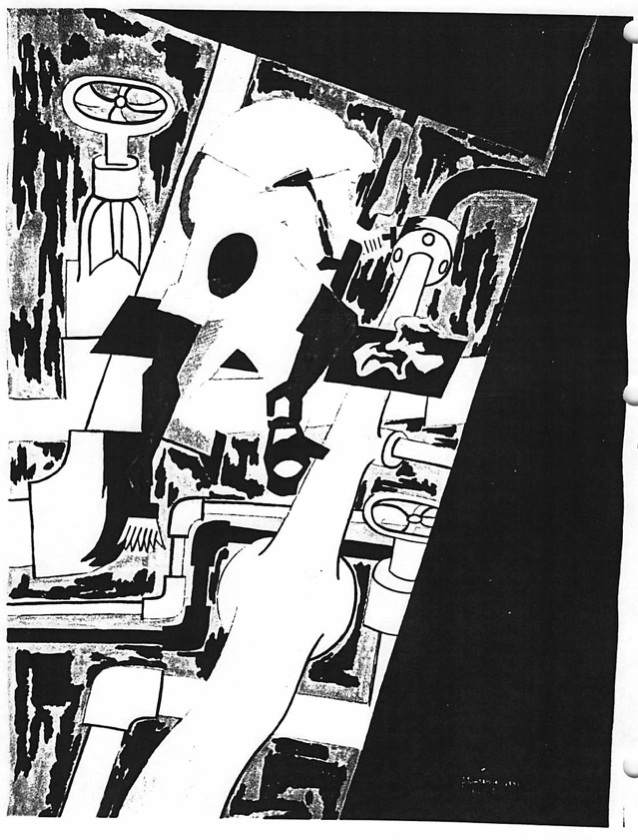

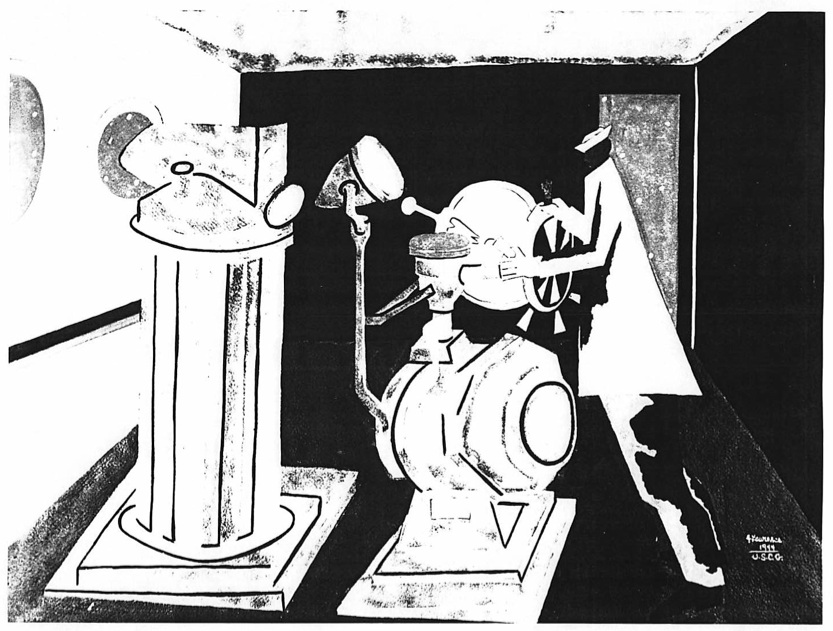

This one, either. Also, it is amazing:No. 2 Control Panel, Nerve Center of Ship, gouache and watercolor on board, Collection USCG Museum

Numbers vary, but it appears Lawrence completed at least 48 paintings while in the Coast Guard. Eight were exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in October-November 1944, alongside the complete Migration Series. [This was the museum’s first solo show for an African American artist.UPDATE: Actually, not. See note at bottom of the post.] The Coast Guard now has only two [above]. Another painting, signed “Jacob Lawrence, USCG,” was donated to the Albright-Knox by dealer Martha Jackson’s family in 1974. And I think that’s where we are right now/the last 40 years.

A history written in the early 90s by Lt Commander Carlton Skinner [pdf, defense.gov link updated 2019], who conceived of the Sea Cloud crew integration experiment, mentions 17 paintings, with one surviving. Milton Brown’s catalogue for the Whitney’s 1974 Jacob Lawrence retrospective says Coast Guard records put the number at 48 paintings, with almost none of the titles or descriptions matching up to any of the photo documentation.

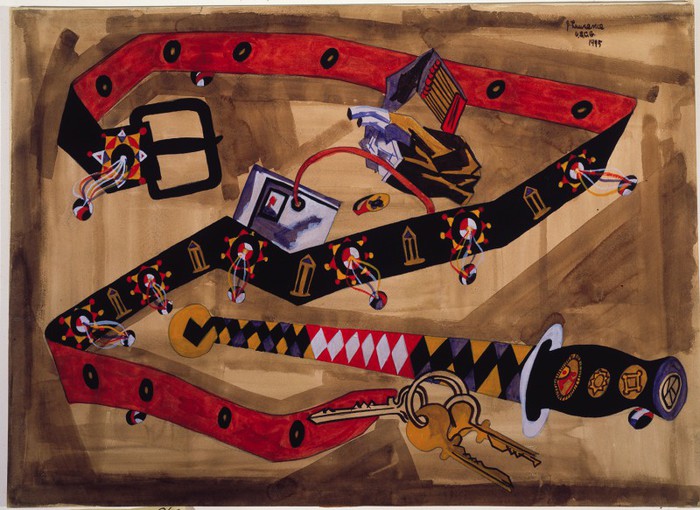

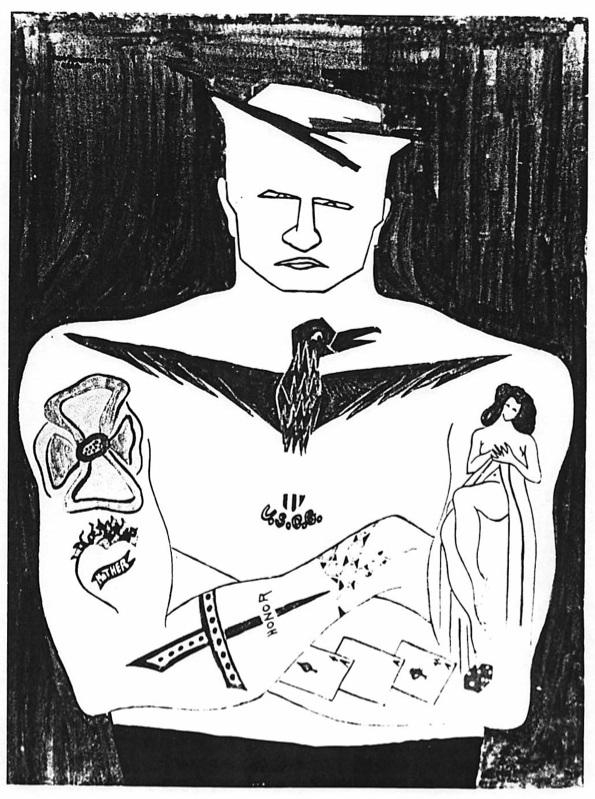

Seaman’s Belt, 1945, was probably painted on the Gen Richardson, not the Sea Cloud. Martha Jackson Collection, Albright Knox Gallery

Skinner says the artwork got lost in the great demobilization shuffle after the war, when paintings just never came back or got tracked after the Coast Guard’s traveling exhibitions. Brown says records for the works stop at 1961, though, and hypothesizes that they were scattered, uncatalogued, to be hung in various Coast Guard facilities. They could also have walked or been tossed out; Lawrence’s intentionally flat style doesn’t read as traditional, high-end Art, and his gouache on paper and panel might not hold up in a non-museum setting. I find it unlikely that no one has researched the paintings or tried to track them down in over 50 years, but so far, I’m coming up empty.

In any case, I’m posting the known images and titles on Lawrence’s wartime paintings after the jump. Let’s find these things, hm?

[CORRECTION Thanks to Anna Monahan of the Phillips Collection for pointing me to the actual first solo exhibition of an African American artist at MoMA: the 1937 show of sculptures by William Edmondson, a self-taught artist in Nashville. As it turns out, Edmondson’s show was held at Rockefeller Center, in a temporary space during the construction of the Goodwin-Durell Stone building. It’s amazing to me that I’d never heard of this period, or this space, even though I just now found a photo of it in Art in Our Time, a history of itself MoMA published in 2004. Will look into it.]

The Lost Wartime Paintings of Jacob Lawrence, by Capt. Carlton Skinner [uscg.mil, pdf]

1974 Whitney catalogue for Jacob Lawrence [archive.org]

Jacob Lawrence (r) with Capt. Jos. Rosenthal and Carl van Vechten at the opening of Lawrence’s MoMA exhibition. via moma.org

MoMA’s show ran from Oct. 10 through Nov. 5, 1944. It was in the Auditorium Galleries, which, hmm. MoMA’s press release [pdf] notes that “almost imperceptibly [Lawrence’s] Coast Guard paintings suggest the gradual beginnings of a solution to the problem so movingly portrayed in the Migration series.” Which fits with the painting above, depicting black and white sailors sharing a table.

[It happens that the next show was Ansel Adams’ “Born Free and Equal,” his book of photos of Japanese-American citizens in a government detention camp. “Their loyalty has been proved,” the similarly forward-looking press release [pdf] asserts. “Thousands of them are in our armed forces. From Manzanar these loyal citizens will move out again into the stream of American life.”]

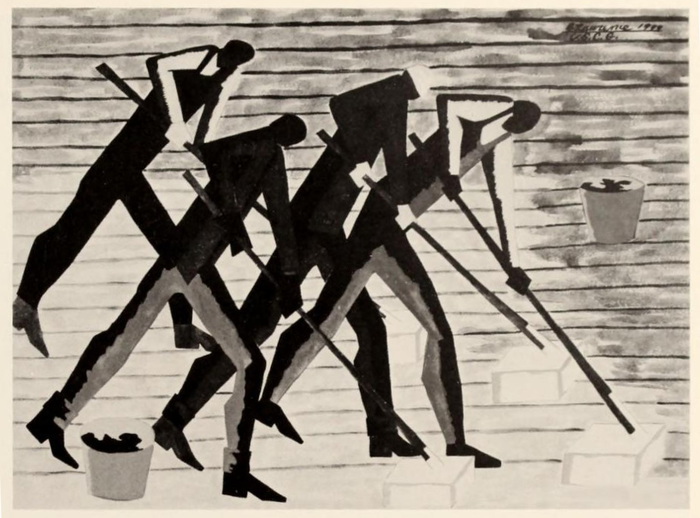

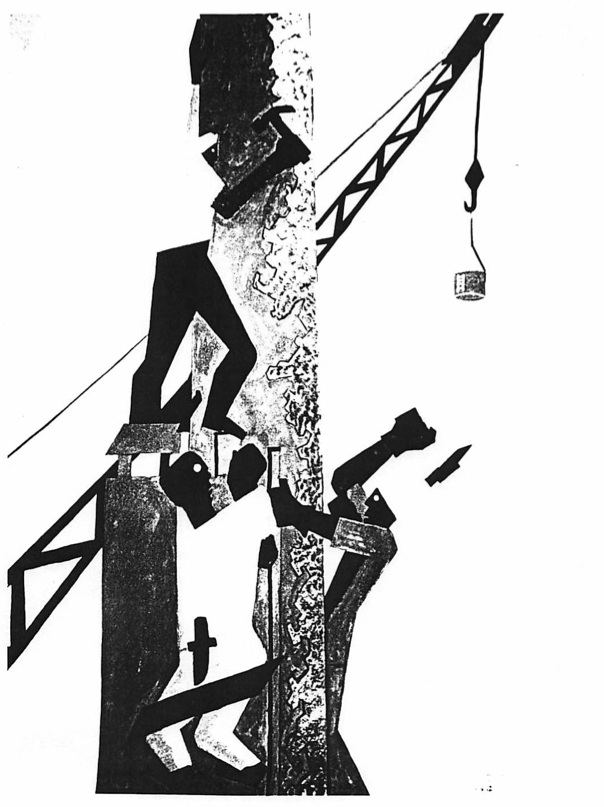

Holystoning the deck was in the 1974 Whitney catalogue as “whereabouts unknown.”

Several of Lawrence’s paintings depict maintenance, operation, and daily life on the ship. Holystoning involves scrubbing decks with pumice-like bricks, water, and sand.

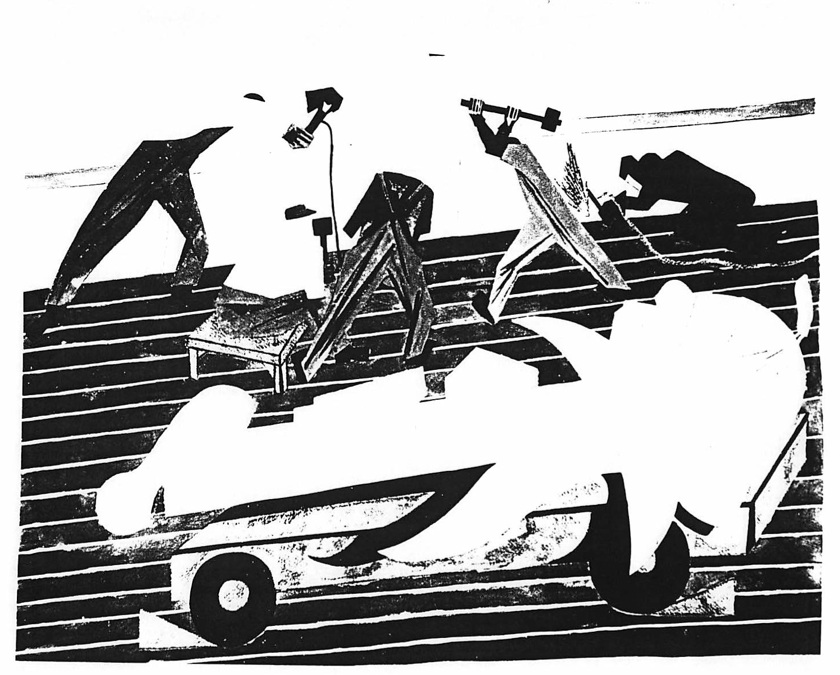

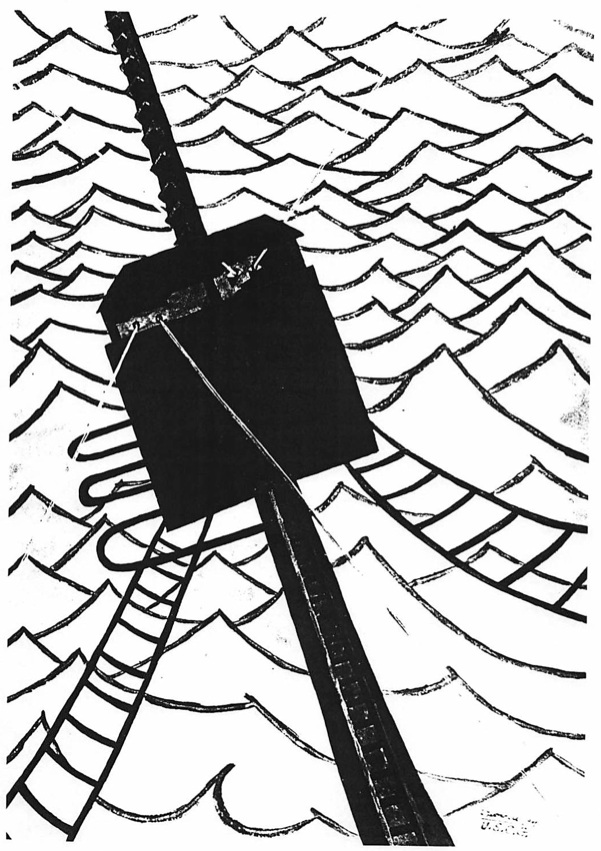

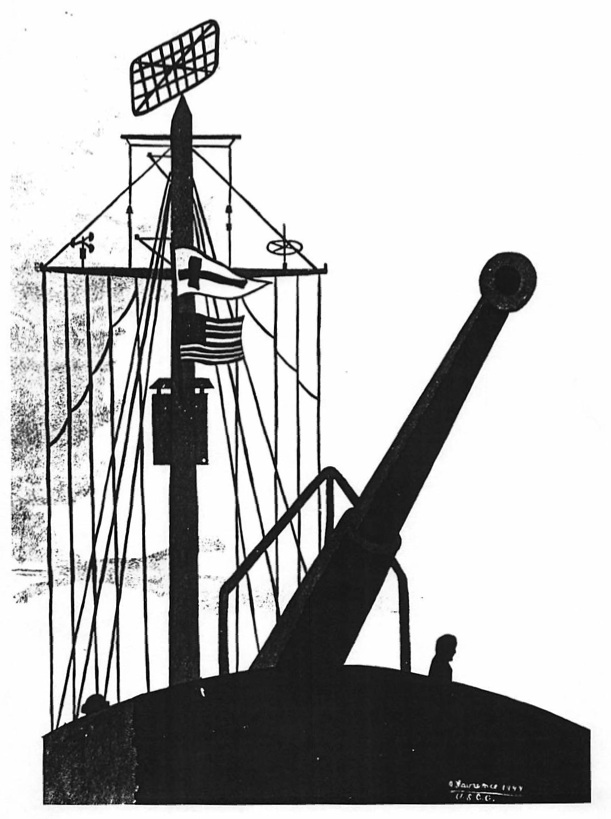

The remaining images come from Skinner’s history, but I don’t know where he found them. There are no dimensions, either, but they’re probably all Lawrence-size. The first two seem to match maintenance-related titles mentioned here: Chipping the Mast and Painting the Bilge.

Some other work on deck.

Lawrence’s dynamics and compositions at sea were similar to the Migrant Series. The two-tone volume on the figures, though, is something he developed post-Migration. It’s in an earlier 1943 painting, The Ironers, and it comes up a lot in the legs and bodies here [like in Control Panel and Holystoning.]

The bridge looks kind of jazzy here.

This is probably my favorite one, a view of the prow of the ship with waves beneath it. Or no, it’s the crow’s nest? Did they still have one? With some kind of vision ray beaming from their eyes? Either way, it’s like those great abstracted, furrowed fields in the Migration Series. Let’s find this one for me, please.

This one’s pretty great, too. Lawrence’s people are so interesting, but so are the pictures without them. This is a pretty big gun to have mounted on a yacht.

It didn’t occur to me until just now that except for a corrupt Southern judge or a club-wielding cop here and there, Lawrence painted very few white people. This guy gets a whole painting:

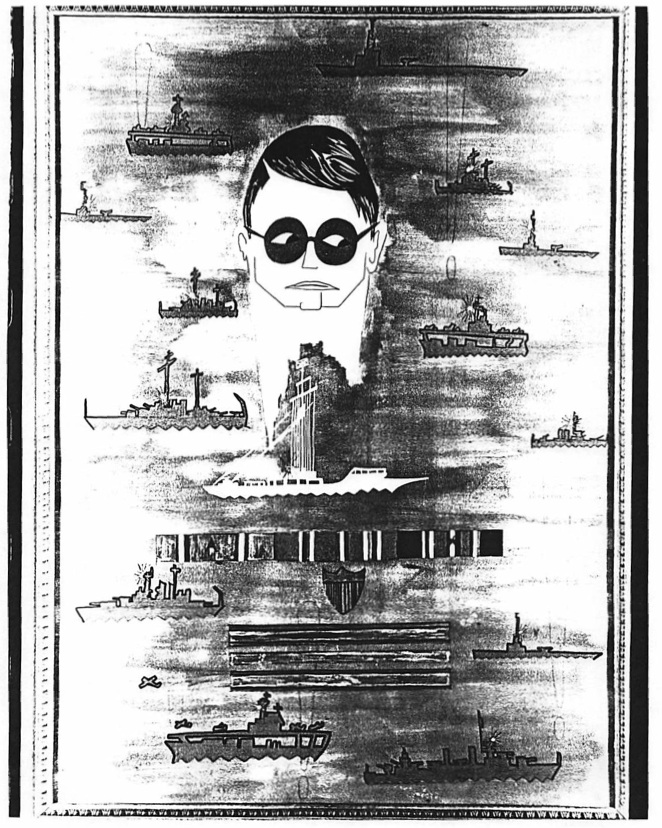

And Carlton Skinner gets a whole, weirdly awesome composite portrait. Apparently he wore sunglasses a lot. This would be a good one to surface, too.

That’s fifteen, at best, less than a third. Most of which seem to come from the Sea Cloud. According to the Whitney catalogue, Lawrence’s paintings on the troop ship General Richardson were almost entirely of the troops. It makes me wonder if Seaman’s Belt is not atypical after all. Maybe he painted other souvenir/portraits, too. Or maybe they’re chilling or working. The fact that Martha Jackson had one also makes me think Lawrence might have painted some for himself, too, off the clock, so to speak. And maybe there are more than what the Coast Guard knew about. Someone has to have some leads on these things, or at least some more info.

[2021 update: archival photos of some of Lawrence’s paintings from his MoMA show turned up for sale at Swann.]

[2022 update: Michael Lobel just tweeted an image of another lost painting titled, “Memory Training”. Please let these turn up in the rumpus rooms of retired Coast Guard veterans.]