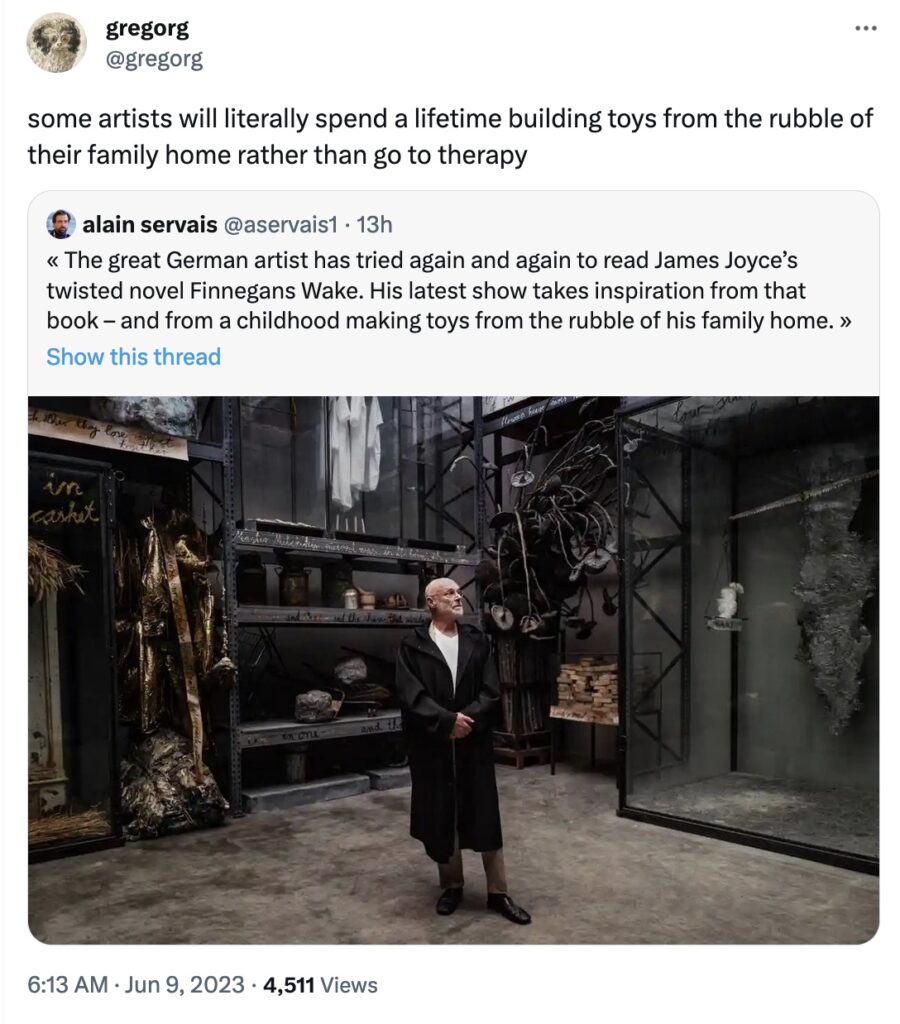

I feel bad for dragging Alain into this, but I’m still trying to grapple with my own offhand comment—on a platform I am working to disengage from, about a column by a critic I avoid—which suddenly upended my perception of an artist I’ve actually liked. So rather than hash it out in a thread I’ll just end up deleting, I’m documenting it here and now.

When I first encountered Anselm Kiefer’s works, it was books, giant painted books, lead books, books with wings, and coming from a culture of metal books, I was taken in. The take on Kiefer then was his boldness in taking on the taboo subject of Germany’s Past.

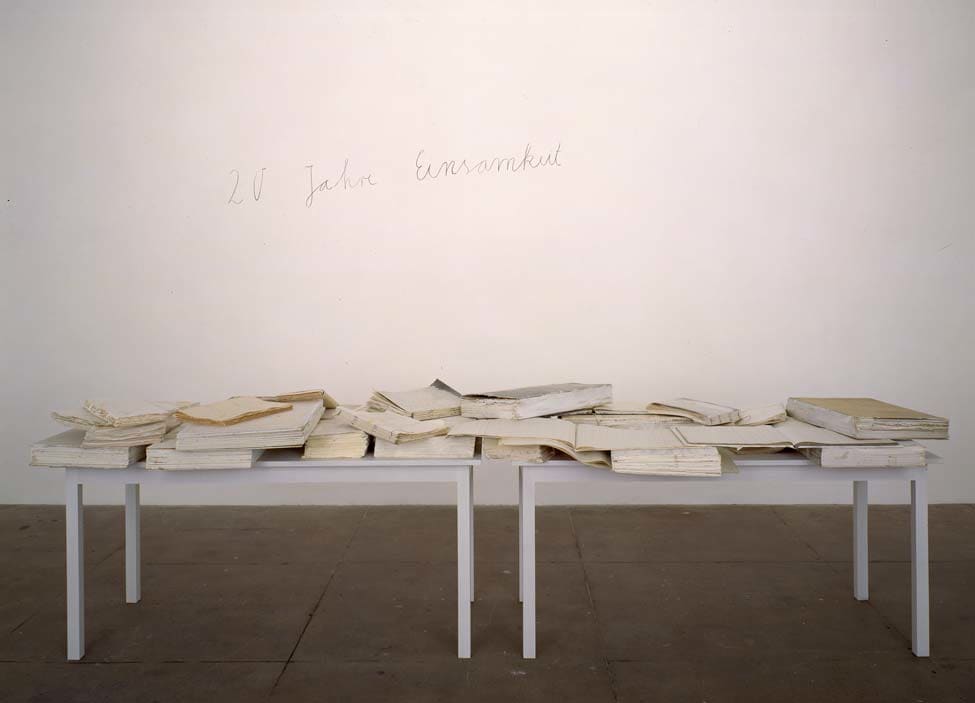

By the time I saw Kiefers in person, though, it was 1993, he’d gone feral. His dealer Marian Goodman was left to exhibit a pile of paintings as they were found in his abandoned studio, along with a table full of ledger books the artist had been masturbating onto for twenty years. The gallery offered white library gloves to visitors who wanted to try unsticking the pages. So yeah, I guess there were signs that something was going on.

Even in this trauma-focused moment, childhood war trauma—for a German kid born in World War II—cannot be the sole explanation for the artist’s project, even if there were such a thing. But the phrase, “building toys from the rubble of his childhood home” suddenly feels expansive enough to snap a lifetime into focus. It’s a parameter that improves the fit of a model to the data that is Kiefer’s art. And yet it also feels like it’s not helping the work, just the opposite. I guess the best case scenario is Kiefer works toward a little more self-awareness and inner peace, and maybe the rest of us don’t have to have so much bombastic Kiefer works in our lives.