Sometimes I really am slow on the uptake. Like when it took me all this time to really look at the extensive installation views of Cady Noland’s exhibition at MMK Frankfurt. Somehow I’d just been stuck with the imageless brochure/checklist, and the works I wasn’t familiar with remained unnoticed to me, even when I should have known better.

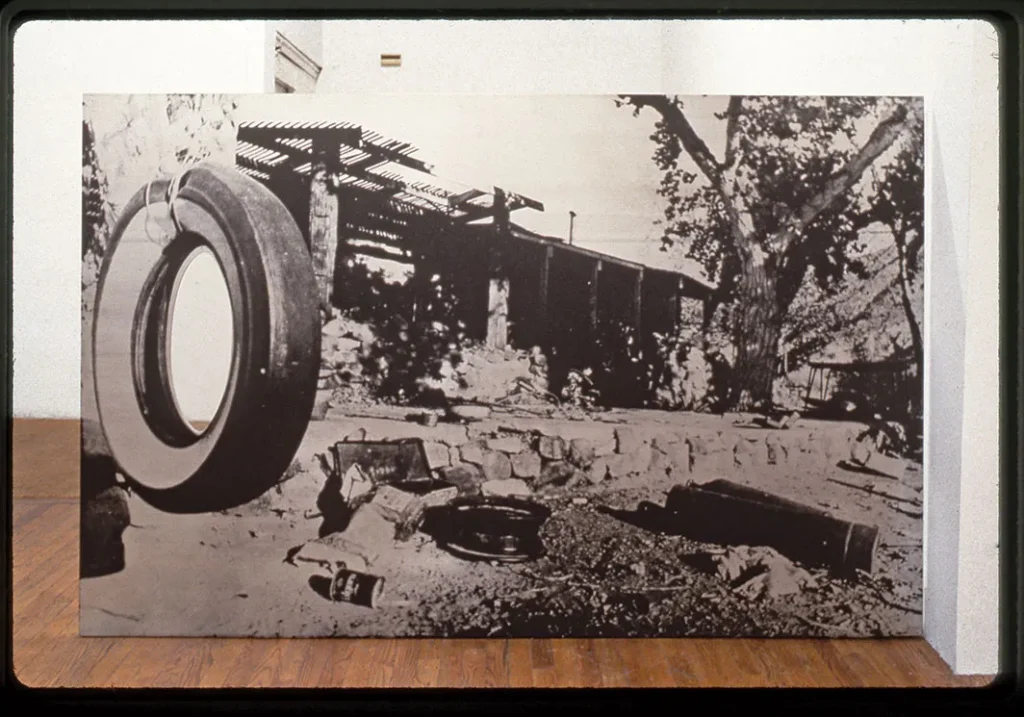

Like Trashing Folgers (1993/94), the large landscape above, a full-bleed screenprint on aluminum of a c. 1969 wire photo of the junked up backyard from Barker Ranch, the post-murder desert hideout of Charles Manson and his “family.” It’s in the collection of FRAC Grand Large in Hauts-de-France, which is on my Lacaton Vassal bucket list, but which does not help me here.

I should have clocked it in Bruce Hainley’s incredible 2019 MMK teaser feature on Noland in Artforum, where Trashing Folgers factored into his revisit of Noland’s 1994 Paula Cooper show. It was in the foyer, first grouping of works you’d see. Of course, Hainley points out that it was facing away from the door, so you approached the back, where the wire service caption for the photo was screenprinted, and the tall, lozenge-shaped cutout was unexplained—it turns out it was from the whitewall tire swing suspended above the coffee can that gave the work its name.

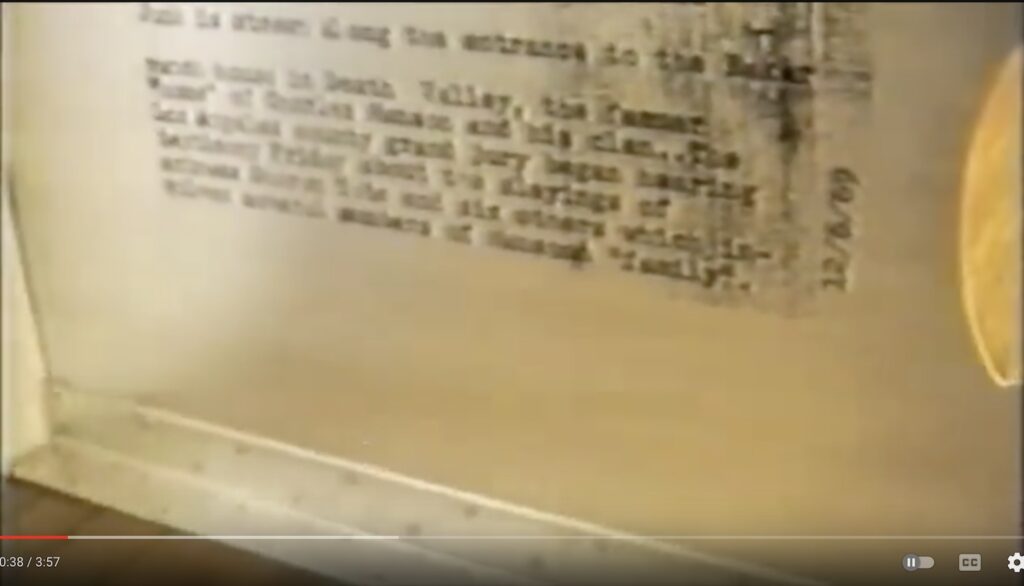

Hainley also notes, with strained forbearance, that the show and the work and the verso are briefly visible on Gallery Beat’s video raid of the show: “Trash is strewn along the entrance to the Barker Ranch house in Desert Valley, the former ‘home’ of Charles Manson and his clan…The Los Angeles county grand jury began hearing testimony Friday about the slayings of actress Sharon Tate and six others which involves several members of Manson’s ‘family’. 12/6/69”

If all I’d missed was a sweet Noland in a regional European collection, I’d be fine. But that tire swing took me out. Because Noland made tire swings, too. And she used the same kind of throwback whitewalls. Publyck Sculpture, 1994, now owned by Glenstone, was in the Cooper show, and MMK, where the explicit connection would have been more obvious.

But it’s also the same kind of tire Noland impaled with a steel tube in the edition she made a few years later. Trashing Folgers was like an opening line for one of Noland’s major shows, and the historical references and material vocabulary kept on going. Or, as in my case, they get pieced together slowly, 5, 30, or 55 years after the fact.

[Next morning update: OTOH, though multiple Manson-related screenprinted works and three tire-involved sculptures are included, Trashing Folgers is not in Noland’s two-volume book, The Clip-On Method. This whole Manson/tire thing, though, is mentioned by Philip Monk in his text for The American Trip: Larry Clark, Nan Goldin, Cady Noland, Richard Prince, the 1996 group show he curated at The Power Station in Toronto, and a catalogue I obviously do not have: “Noland’s free-standing swings (wickedly titled Publyck Sculpture, suggesting that the first public sculptures were public stocks) now find resonance in their duplication in the silkscreened images of the backyard garbage dumps of the white-trash Manson family (see Trashing Folgers).”

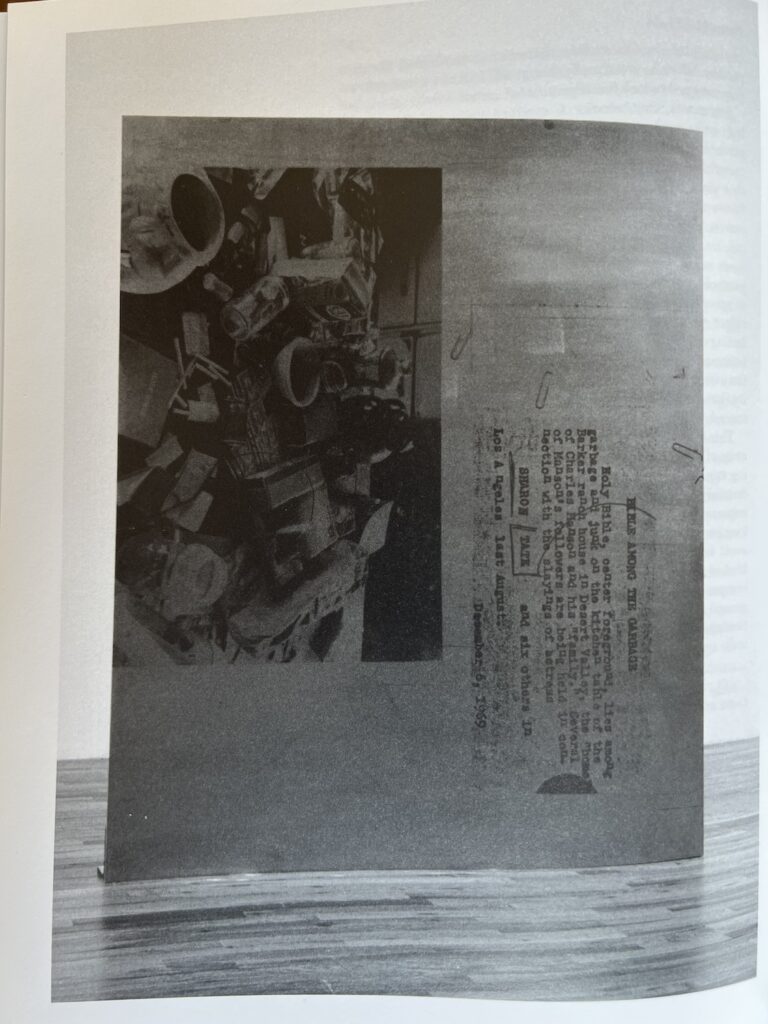

Monk, further on: “If we can extend the intuition that blank identity is to iconography as anonymity is to fame, then we can interrogate not only the relation of each term to its other but the relation of one set to the other, as well. In turn, they become the grid for interpreting Noland’s works. In this light, compare Trashing Folgers with its image of the chaotic garbage heap of the Manson backyard or Bible Among the Garbage to the Gestalt media icons of Manson, such as Mr. Sir. Even in his collapsing state, Oozewald (Oswald) among the heap of materials in Noland’s 1989 installation Deep Social Space asserts the same relationship of icon to surrounding, Gestalt to fragment.”]