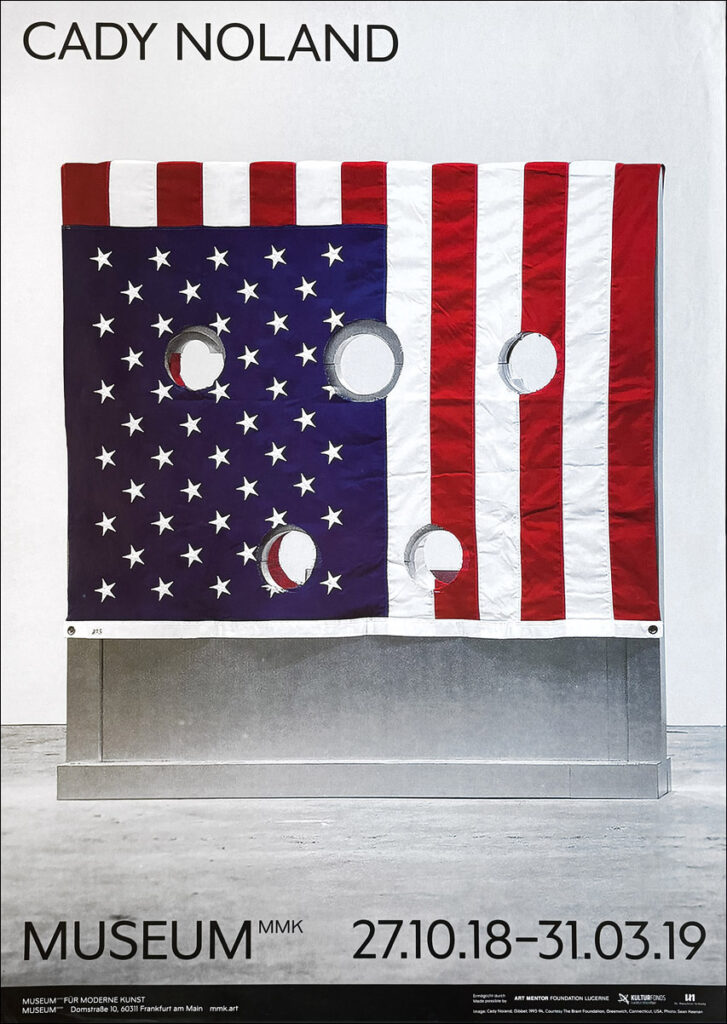

Cady Noland, MMK, 2018, €350 [bentpriorities]

the making of, by greg allen

Cady Noland, MMK, 2018, €350 [bentpriorities]

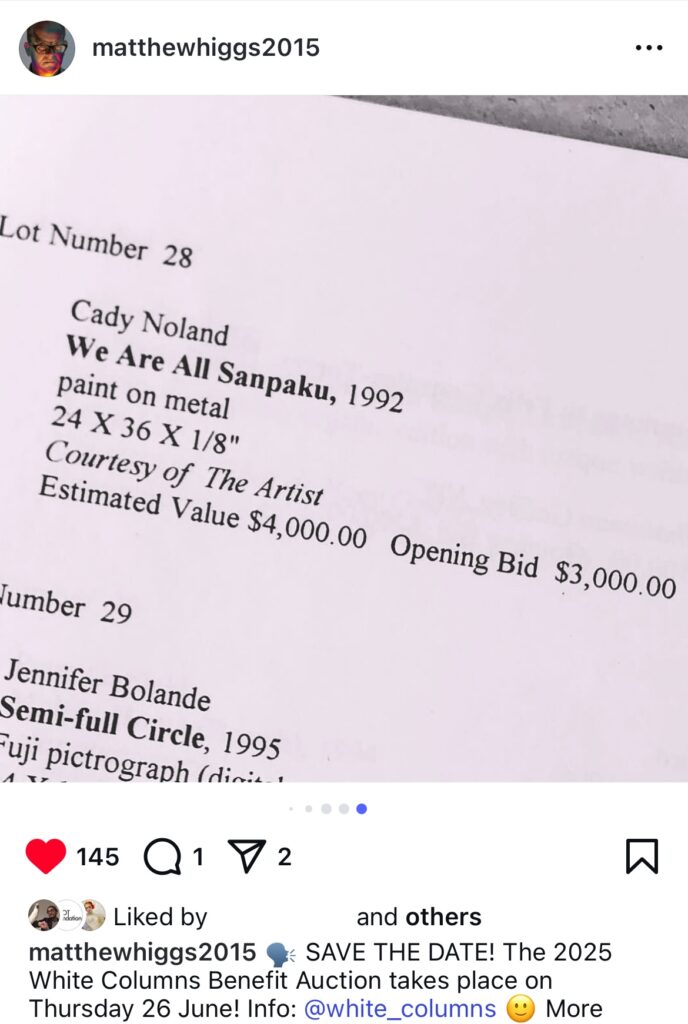

White Columns’ archives have a lot of amazing stuff, but not all of it. Director Matthew Higgs regularly posts outtake gems to his instagram, like he did yesterday when he announced the upcoming White Columns Benefit Auction (June 26, tickets and exhibition start next Friday) by posting some pics of previous benefit auction checklists.

Like this one from at least 1996, when Cady Noland donated a work from 1992 that does not appear anywhere else in the public record. What is/was it? A cozily sized screenprint on aluminum, sure, but of what?

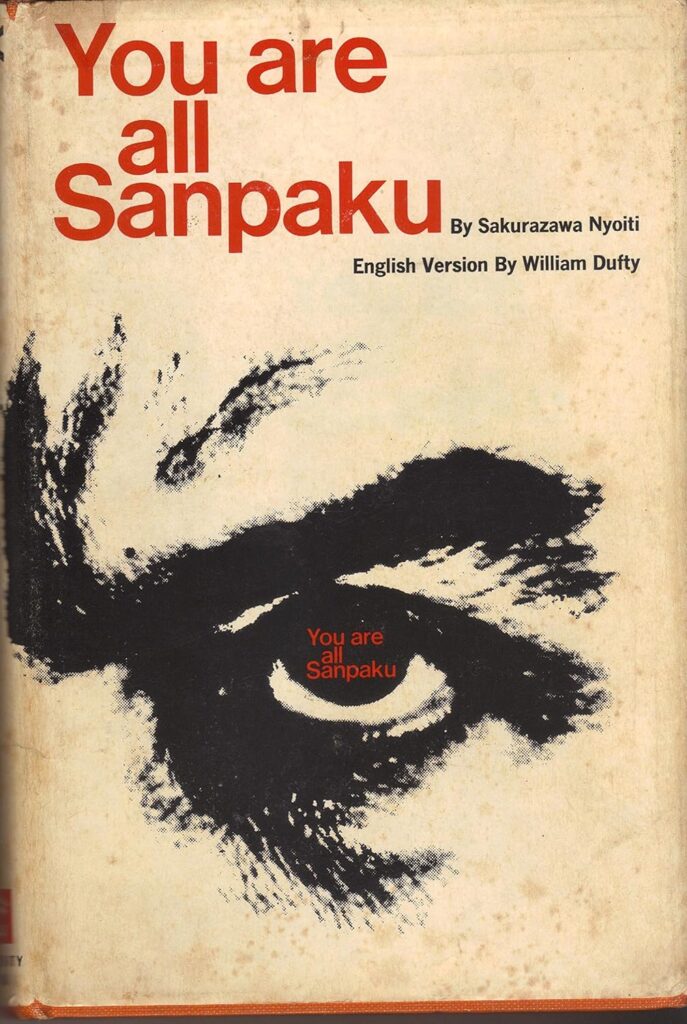

We Are All Sanpaku is a phrase that probably felt so culturally obvious at one point that it was hard to imagine having to explain it. But We Are All Sanpaku’s moment was not 1992. It had already reached New Yorker cartoon punchline by 1985. Nixon was sanpaku, and—most crucially here, I think—Charles Manson was sanpaku, too.

We Are All Sanpaku is the despairing public’s confessional response to the 1965 declaration, You Are All Sanpaku, a best-selling book on Japanese physiognomy and macrobiotic diets by a guy with at least six aliases, including Georges Ohsawa. Sanpaku, three whites, is when the sclera, or white of your eye, is visible on three sides of the iris, rather than the normal [sic] two. Like your blood type and being born in the year of the goat, sanpaku has dire health, psychological and prophetic implications.

After diagnosing the western world—and the most prominent people in the news in the 1960s and 70s, including JFK, Marilyn Monroe, John Lennon, Nixon, and Manson—with not meeting Japanese beauty standards, Ohsawa said it could be cured with brown rice.

Which, whatever, my point here is that the aesthetic possibilities of what Noland painted on that metal sheet are a rich feast, and I want to see it. Charles Manson’s mugshot that ran on the cover of LIFE? The ominous eye from the first edition dust jacket? Nixon? In the spirit of sanpaku, I might just make something up and pretend it’s real.

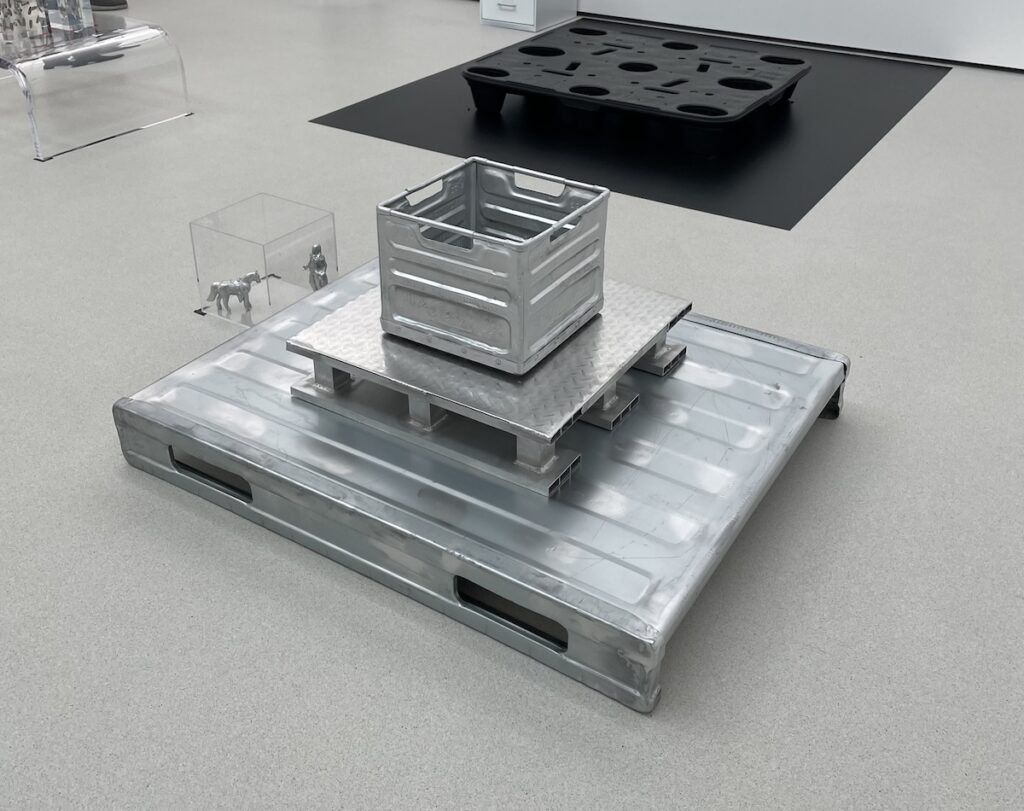

Now that she’s been having some shows, Cady Noland is known to make changes to installations of her work, even dramatic ones, even last minute. So maybe it was not so surprising to realize she added a new work to the exhibition at Glenstone last October, which came so late in the process it did not appear on the museum’s downloadable checklist.

And while there were also shipping palettes from Amazon stacked in the gallery that were also not on the checklist, the status of this work, Untitled (2024), was only uncovered/confirmed three weeks later, when Alex Greenberger reviewed the show for ARTnews. And it took still more weeks to add it to the checklist, the only prepared information available to visitors.

At the time, I wrote that such a move was not an error: “This incompleteness, this inaccuracy, is part of the encounter; this disconnect between what you see and what you’re told is part of the experience.”

Well, now I wonder if it might have been omitted for reasons other than coy mystery. Because the most prominent elements of the work Noland added are a palette with the Amazon sticker still attached, and a milk crate stamped with a threat from the Pinkertons. The Pinkertons who chase down milk crate thieves, but who are most famous for attacking striking steelworkers on the orders of Andrew Carnegie and Henry Frick.

I had not realized that last summer, before the museum had fully reopened from its remodeling, Glenstone’s hourly workers voted to form a union, and that the Raleses had hired the same anti-union lawyers and consultants as everyone else—including Amazon. Kriston Capps reported on the union’s efforts and voting almost a year ago. That would have been right around the time Noland was installing her show.

There is not much information beyond Capps’ early reporting. The last post on the instagram account for Glenstone Museum Workers Union, affiliated with the Teamsters, was from November 22nd. It says two bargaining sessions were completed, in September and October–and that the November 2024 meeting had been canceled without explanation. A December meeting was TBD. Noland’s show opened October 17th, in what seems to be the middle of a breakdown of negotiations.

To drop a pyramid of unionbusting references in the center of the gallery could be read as a show of solidarity with the union. If anyone knew to look. Now the prolonged omission of the Pinkertons work from the checklist feels like it could have been a move to deflect or diminish the impact of Noland’s gesture of support.

Unless? Do we really know that Noland’s invocation of the Pinkertons thugs isn’t a shoutout to management, an homage to the Fricks of our day, the industrialist connoisseurs who bought basically every major piece of the artist’s work to come up for sale in the last twenty years? If it was, maybe Glenstone would have bought it. Or they would have at least included Noland’s loans in the documentation of the show.

Previously, related: Cady Loan’d

Instead of posting an artist disclaimer on a work for sale, Sotheby’s just cites its appearance in the artist’s book, and the four three museums, public and private—and whatever Peter Brant is doing—which hold other variations on the work. Whatever else is going on in the world, we do live in a Golden Age of Cady Noland Marketing.

16 May 2025, lot 529: Cady Noland, SLA Group Shot With Floating Head, 1991 [sothebys]

For the first time in several years, Christie’s has *not* published a disclaimer from the artist when it brought a Cady Noland sculpture to the market. And boy, does it need one, so let me try:

Continue reading “My First Cady Noland Disclaimer”

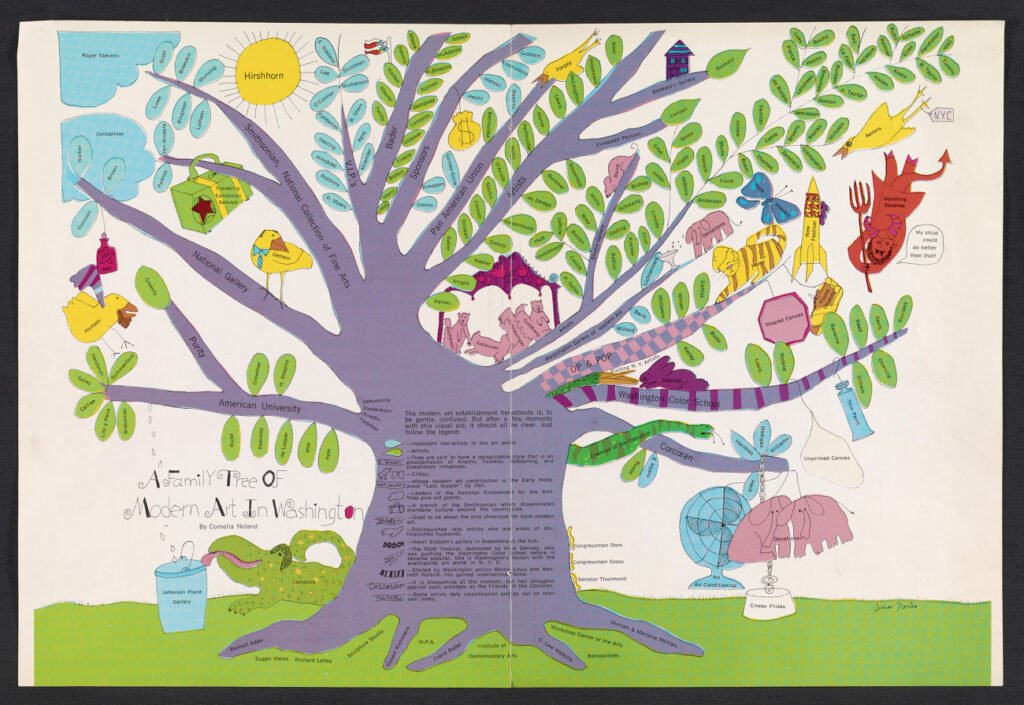

While researching the Pan American Union in the Archives of American Art, I stumbled across this two page spread from the 1960s, “A Family Tree of Modern Art in Washington, by Cornelia Noland.” It is a little snarky, a little petty, but quite revealing? “The modern art establishment here is, to be gentle, confused,” Noland wrote.

Continue reading “Cornelia Noland Art Family Tree”Looks like more writeups of the Cady Noland installation at Glenstone are turning up—and more images of it are getting out. Ian Ware at 202 Arts Review has apparently found the same stash of Noland photos online—though he is more assiduous in his image copyright crediting than I was.

And that’s all reason enough to rejoice. But beyond that, Ware has a very interesting, site-specific take on Noland’s take on her works’ new home. He finds a relationship between the temporary walls Noland erected to block a distracting view of the museum’s pond, and the museum’s own temporary walls blocking off the building’s renovations.

He also sees in Noland’s alterations and additions to the installation a critique of the Raleses and their multibillion-dollar project. Here he draws on the larger context of the Raleses’ business dealings and Glenstone’s construction–and the lawsuits with its contractor that precipitated the current closure and renovations of the new museum building—and even some of the lurid investment shenanigans by the contractor’s family—a local real estate dynasty, apparently—that “may as well have been written for a tabloid delivered straight to Noland’s doorstep.”

What feels more resonant—and which I think takes more properly into consideration the involvement of Emily Wei Rales, in curating, collecting, and institution-building—is the exhibition of Noland’s work alongside the text collages of Lorraine O’Grady and the powerful sculptures of Melvin Edwards.

As someone who’s watched the Raleses develop their vision from various vantage points, I feel like they’ve been thoughtful to iterate away from the narrow trophyism of, say, the Fisher and Broad collections. The collecting path from Split/Rocker did not have to lead to Noland, or O’Grady, or Edwards, but here they are. If they do take a couple of hits from an artist they think is significant, I imagine they’d be undaunted, maybe even appreciative. Their venture faces more credibility risk from privileging artists’ approbation than from accommodating their critiques.

But this gets to the crux of Noland’s work today, when the poisonous forces of media, politics and power have outstripped everything she flagged back in the day. Can her new work make a similar impact to her earlier hits? Is that even something she considers? Or does the proliferation of objects trapped and neutralized in acrylic blocks, perched on industrial logistics flotsam target a new, contemporary source of dread we’re still too asleep to realize? And does this luxuriously contemplative installation help us to see, or does it sedate us?

The House is (Still) on Fire, But There’s a Cady Noland Show to See. [202artsreview]

“Beginning October 17, and spanning three rooms of the Pavilions, Glenstone will share a presentation of works by Cady Noland. Developed in collaboration with the artist, this presentation will mark the first major survey by a U.S. museum of her decades-long career.”

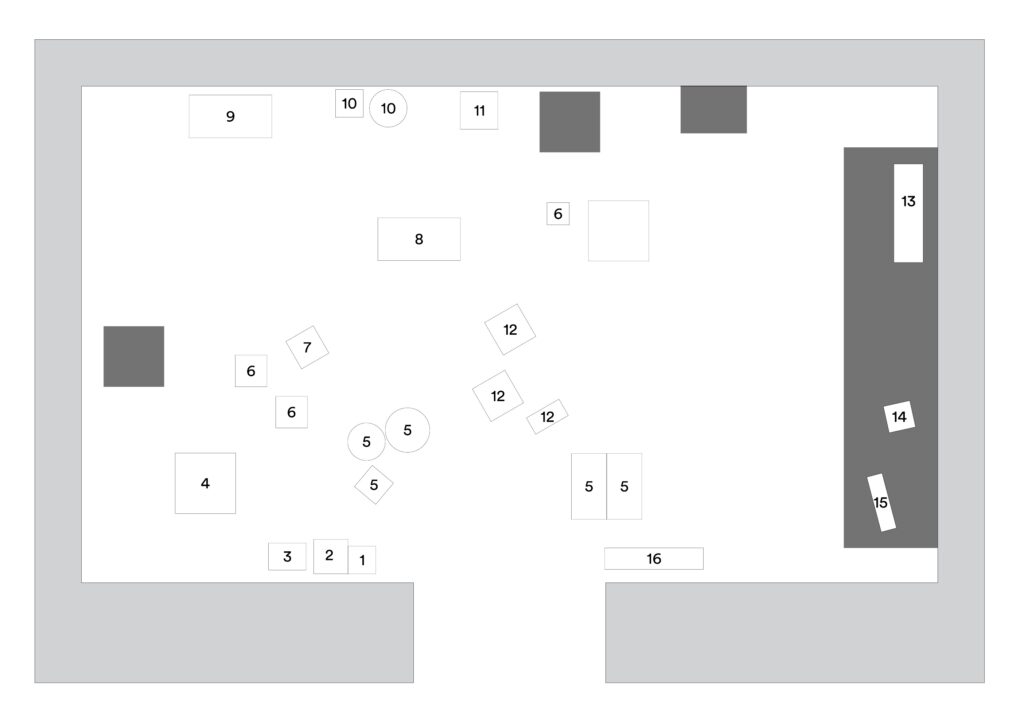

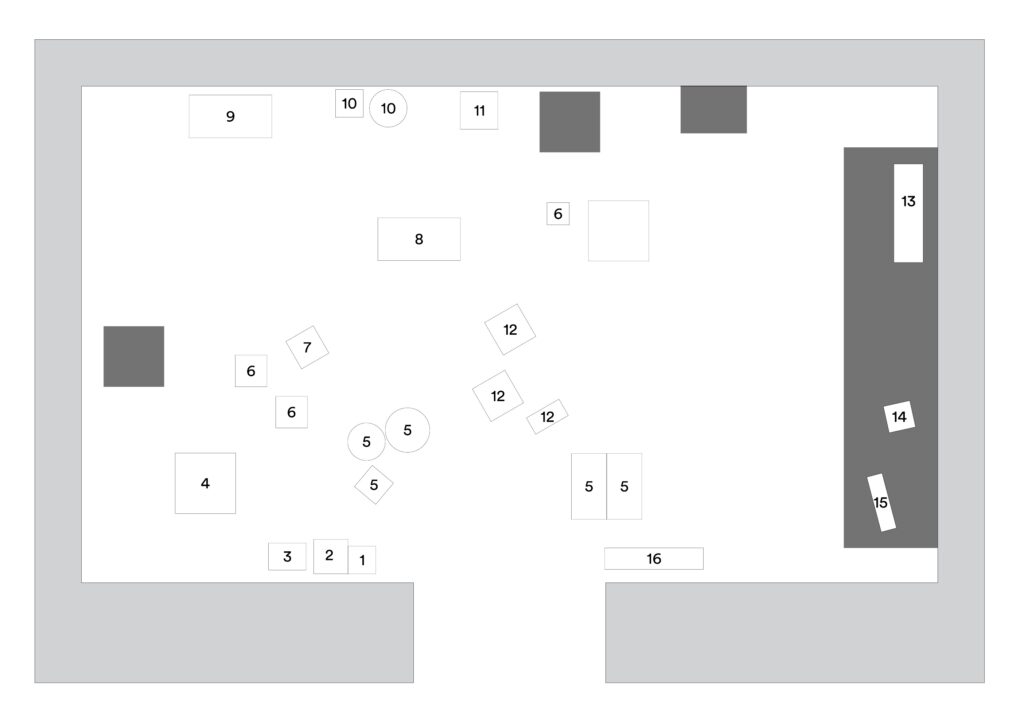

Reader, the presentation has been marked. Last year I poured one out for anyone who’d hoped to buy a new Cady Noland work. But now I feel for anyone who’s been trying to buy a major Cady Noland the last 17 years. Because Glenstone got them all. Look at that map; Glenstone has Cady Nolands even Glenstone doesn’t know about.

Three of the six open pavilion spaces are Noland’s work. [The others are two galleries of works by Lorraine O’Grady and Melvin Edwards, and the little library.] The first thing you see as you go down the stairs is not a Noland sculpture, but a Noland architectural intervention. At first it read like an Ellsworth Kelly, if only because architecture-scale Kellys were just on view here. Up close, no, closer, inside it, it read like an Anne Truitt, of the back of the Anne Truitts that had backs.

The no photography proscription is excruciating, and I find myself trying to no spoilers my way through this post, as if it’s feasible to say, let’s discuss it after you’ve seen it. The artist adjusted the space to minimize distraction and focus attention on her work, and it works. They borrowed Clip-on Man. Charles Gatewood’s book with the source image is in the library.

The Raleses purportedly acquired Noland’s entire show last year at Gagosian, but it also somehow fills a space three times the size. There is a lot less tape, except when there isn’t.

There are pallet plinths that are not elements of the work, except when they are. There are foam and carpet blocks that precede an installation, except they’re still here. It’s at once pristine and provisional.

The paper labels remain on the white wall tires. You may not ride the tire swings. The internal gear to lift the massive stockade is freshly lubed, but the crank is padlocked. The chain that connected the bench is gone. Oozewald has its corrected and copyrighted stand. The wear on the corners of one (non-mirror-finish) aluminum panel propped on the floor is enough to make the owner of Cowboys Milking weep.

It’s like this survey surveys not only the range of Noland’s work as she made it, but as it was presented, processed and purchased since. Maybe being cast in acrylic and thoughtfully placed in the contemplative suburban art temple of benevolent billionaires is not, after all, all bad.

I was excited to read Nicole Acheampong’s feature on David Hammons in art issue of The New York Times’ T Magazine because I knew it would focus on some of the artist’s less documented works off the beaten art world path. [They’d asked me about images of Hammons’ public artworks in Savannah, but opted to not go the appropriated Google Streetview route.] And it does, and it’s great, and it’s especially nice for pointing me back to a profile I misesd in 2018 by M.H. Miller of LES publisher, poet and longtime Hammons whisperer Steve Cannon.

Cannon is one of the creative suns like East Village photographer Alex Harsley who looped Hammons into their regularly orbit from the early 1990s. In the white artworld, Hammons developed a reputation of being aloof, reclusive, evasive But the truth is, he just had his own people he’d rather be in dialogue with, and Cannon has definitely been one of them.

But I was stunned to read Julia Halperin’s cover story about Cady Noland, which tracks the artist’s rise, her apparent withdrawal from the art world—and the rumors or sniping around it—and her recent return to exhibiting her work. Noland’s dedication to the precise positioning and presentation of her work is an ongoing theme, along with the power her work derives from attention some saw as excessive.

I was stunned even though I’m quoted in the article—as “a Noland obsessive,” which lmao is going straight on my bio—stunned because though she refused an interview, Noland agreed to respond to Halperin’s inquiries. The article is thus replete with parenthetical denials of rumors and clarifications of others’ statements, as if she’s carefully correcting the position of each element in her narrative.

Noland also provided the Times with previously unpublished Polaroids. And they confirmed that the artist has been involved in the new installation of her work opening at Glenstone in less than two weeks. Also that the Raleses did indeed buy out her entire show at Gagosian. What is a collector but an obsessive with ten billion dollars?

The Secret Art of David Hammons [t mag]

A Blind Publisher, Poet—and link to the Lower East Side’s cultural history

Cady Noland and the Art of Control

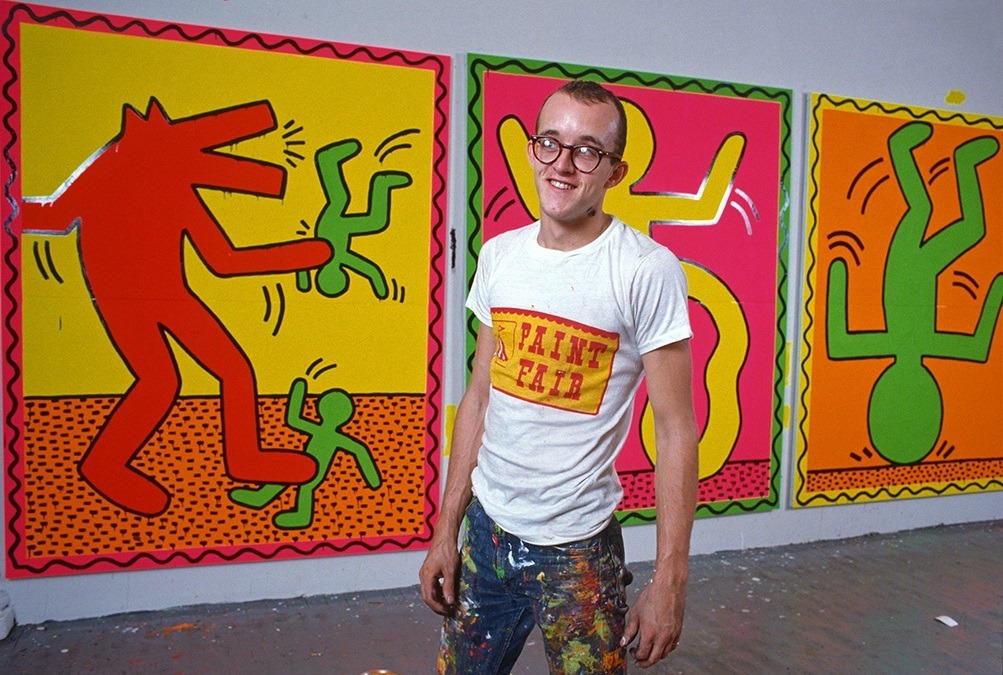

Poking around The Broad’s Keith Haring show, which is at the Walker for another week or so, led me to this photo of Haring at work. It was taken in late 1982 by Alan Tannenbaum. I feel like I’d seen images of this moment before, but this time, what caught my attention was Haring’s t-shirt.

Paint Fair, in carnival lettering with a circus tent and a frilly, scalloped, tent-like border.

I noticed it because it looked very similar to Nuts’N’Shit, a screenprinted metal work by Cady Noland and Diana Balton. The one at MoMA [above] is listed as a screenprinted edition of one, but the one in Frankfurt was enamel, framed, and from the Brants. I will trust the artist to sort that out.

Continue reading “Paint Fair, Nuts’N’Shirt”

Sometimes I really am slow on the uptake. Like when it took me all this time to really look at the extensive installation views of Cady Noland’s exhibition at MMK Frankfurt. Somehow I’d just been stuck with the imageless brochure/checklist, and the works I wasn’t familiar with remained unnoticed to me, even when I should have known better.

Like Trashing Folgers (1993/94), the large landscape above, a full-bleed screenprint on aluminum of a c. 1969 wire photo of the junked up backyard from Barker Ranch, the post-murder desert hideout of Charles Manson and his “family.” It’s in the collection of FRAC Grand Large in Hauts-de-France, which is on my Lacaton Vassal bucket list, but which does not help me here.

Continue reading “Cady Noland Tire Swing”

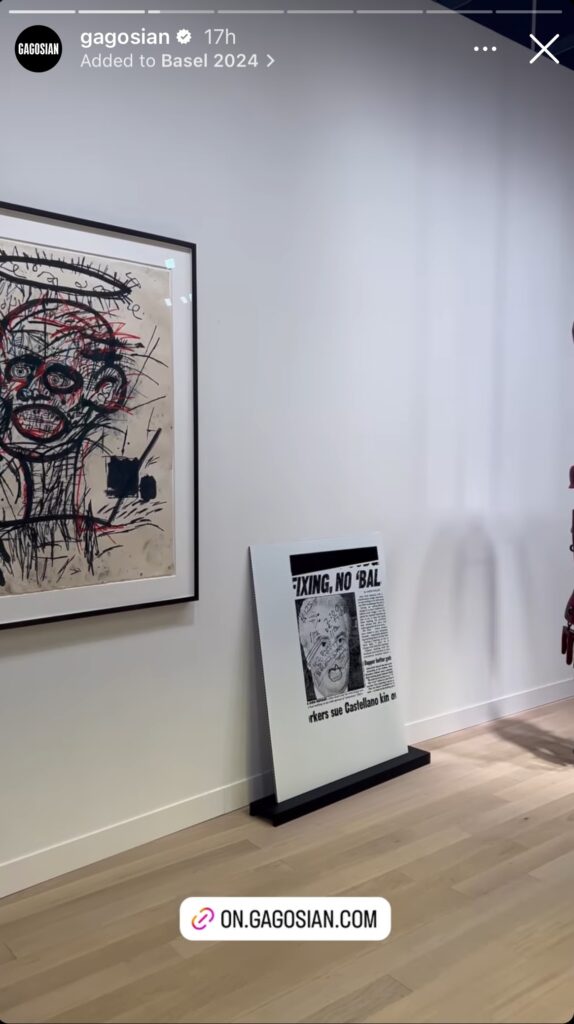

HO HO, what’s that on the floor of the Gagosian booth at Basel, between that 1990 Judd stack Zwirner also repped, and that 1990 Christopher Wool painting of Thompson Dean’s that Christie’s ended up with after it didn’t get one bid in 2021?

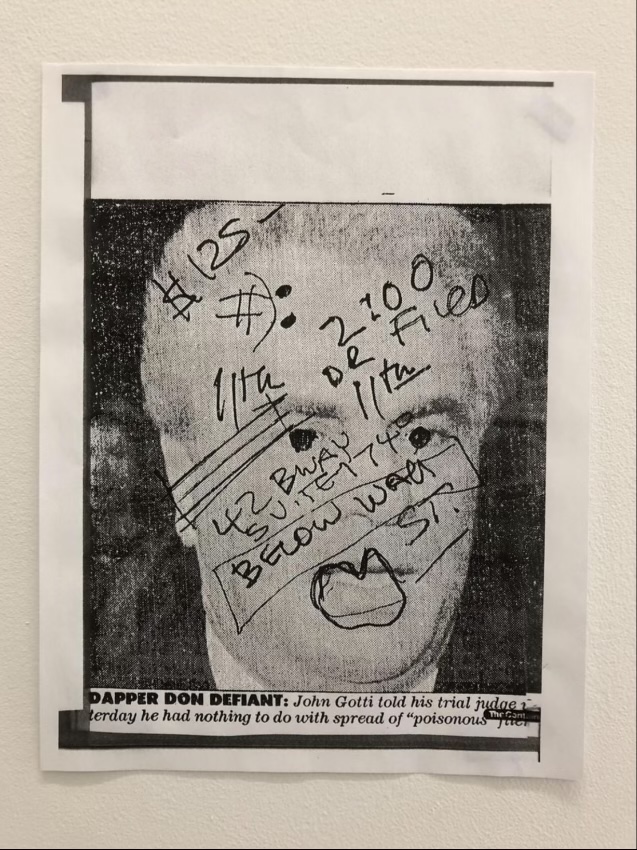

It is a Cady Noland with a 1990s subject—a NY Post article on mobster John Gotti’s 1992 trial—but a fresh, 2024 date.

What does it mean that Noland put out a work in 2024 about a vain mobster nicknamed “the Dapper Don” being called out by the judge for trying to poison his trial by threatening witnesses? What does it mean that she seems to have made this work out of the same photocopy Andrew Russeth spotted five years ago, in Joanne Greenbaum’s wild 70+ artist group show, “Notebook,” at 56 Henry? [n.b.: “Notebook” closed a couple of weeks before the MMK retrospective opened.]

Did Noland look around her studio and laugh as she considered Greenbaum’s request for one notebook drawing or work they “would never show to a dealer or pull out during a studio visit”?

And the plinth? I just listened to Jeannine Tang’s talk at the MMK symposium that included several quotes from Noland and her sources about the problems of plinths. But I guess they’re OK for high traffic art fair booths?

There is another new Noland in Basel, a wire crate-o-stuff, and if I see the photo again of the guard-like woman standing next to it, I’ll post it here.

UPDATE: Meanwhile, here is what I understand is the piece Noland included in Notebook at 56 Henry in 2019. No date was forthcoming, but it is not, in fact, identical to image silkscreened on the 2024 work. It looks to be a cropped variation, copied with paper strips placed over the elements Noland wished to exclude. There is a little anomaly in the right side of the Gotti caption, which looks like a logo for The Container Store. Is it perhaps a trace of a plastic document sleeve, that might also be the cause of the uneven edge? It’s a narrow window into a practice few people even knew in 2019 was active. If, indeed, that was when Noland made this copy.

Previously, related: “we woke up in a world where Cady Noland makes and shows work. At Gagosian.”

This post will be updated as more motivs emerge.

Of all the work remaining to be sold from Chara Shreyer’s fascinating collection, there’s a lot to like. But nothing lands quite like this Cady Noland sculpture. It’s labeled as Patty Hearst Wooden Template, though the aluminum version at MoMA is titled, Tanya as Bandit.

Also this one is dated 1989-90, while MoMA’s—which one would think was created using this template and the instructions written on it in marker—is dated 1989. Maybe it took a little longer for Noland to decide this, too, was a work. But I don’t know, and as the artist’s statement to Sotheby’s makes clear, she was not consulted:

Statement from the Artist:

In an atmosphere of rapidly trading artwork, it is not possible for Cady Noland to agree or dispute the various claims behind works attributed to her. Her silence about published assertions regarding the provenance of any work or the publication of a photograph of a work does not signify agreement about claims that are being made. Ms. Noland has not been asked for nor has she given the rights to any photographs of her works or verified their accuracy or authenticity.

Me, I’d also ask her about that base, when there’s a wire on the back for hanging it.

Lot 456: Cady Noland, Patty Hearst Wooden Template, est. $50-70k, update: sold to someone else for $88,900 [sothebys]

Previously, related: An Anthology of Cady Noland Disclaimers

Tania Facsimile Object (N1)

There has been surprisingly little written about Cady Noland’s show at Gagosian’s Park & 75th Street storefront space. I’m not gonna lie, I don’t know quite what to make of it all, either. All the years of absence and anticipation just end, and people maybe don’t quite know what to do or say. In the last 20 years, Noland’s practice has been understood as a harbinger, coming from the past, with relevance for the present. In the 80s and 90s she threw the dodgeball of prophecy about American violence and celebrity politics and art world commodification at our heads, and every disclaimer, auction record, and lawsuit of this century was another hit.

As Noland’s first show of new work, and a lot of it, in decades, it’s easy to want it to be important. But now that means figuring out what it’s doing now; is it relevant in this moment, or is it yet another harbinger?

Continue reading “Let’s Review The Tape”