Once I could confirm she included no LL Bean tote bags, I made my peace with not blogging every review and post and image of Cady Noland’s one-room exhibition at Gagosian. But it’s hard to resist, especially in this window before I get to the show in person.

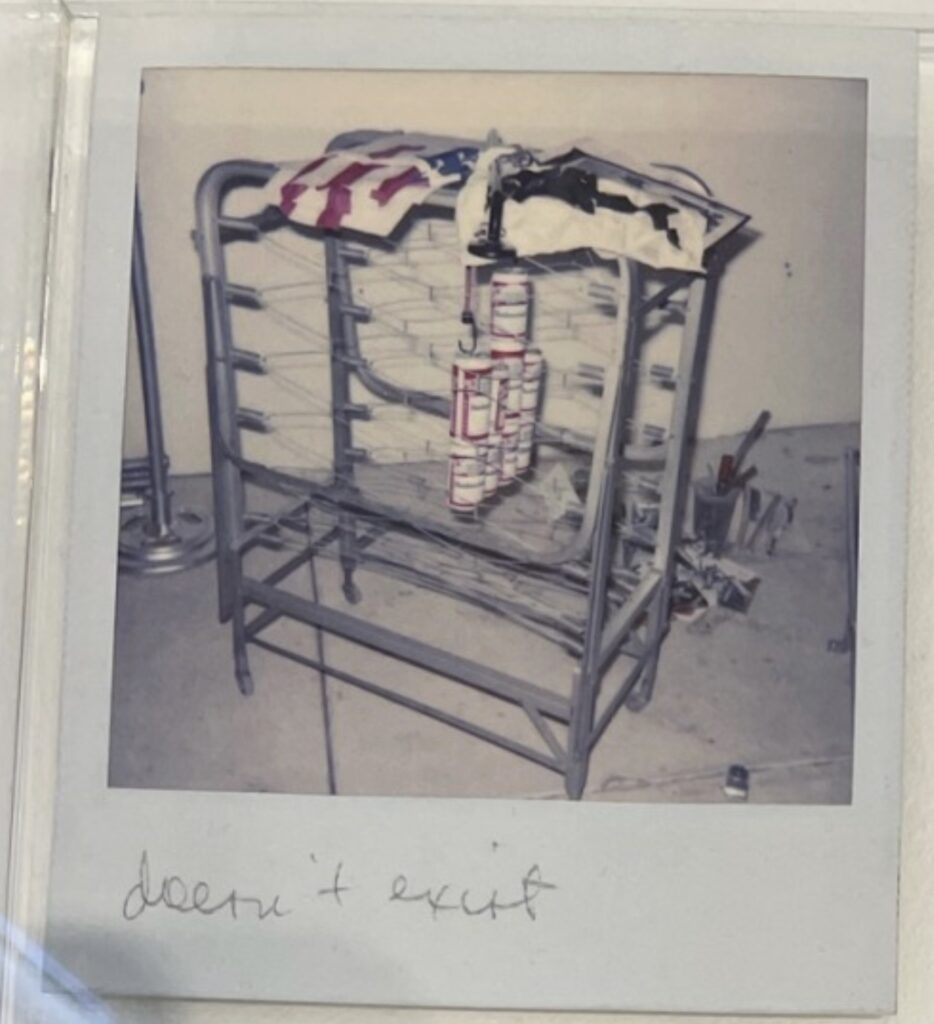

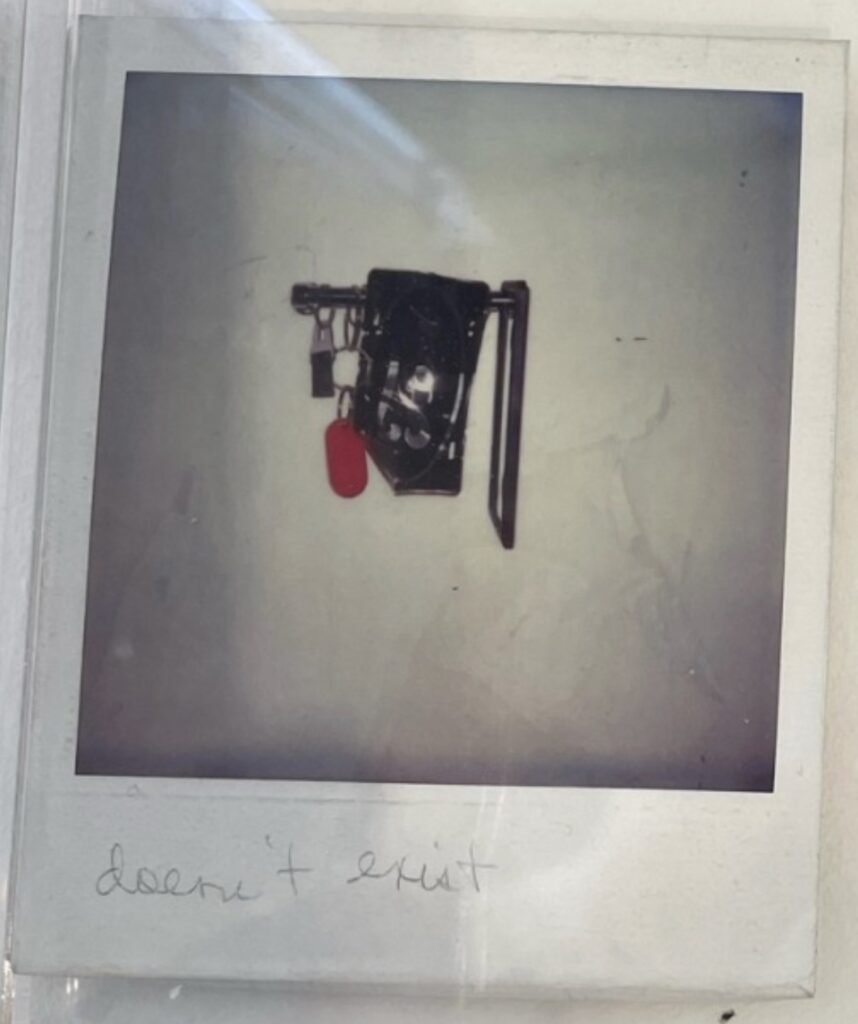

On tumblr Octavio has posted some intriguing photos that were not in the gallery checklist: a collection of archival Polaroids, some stacks several pictures deep, of earlier installations and details of work. I’m going to wait to go through them more carefully, but I will absolutely rush to post the discovery of a new category of Cady Noland sculpture alongside “destroyed by refabrication” and “disavowed because of damage and conservation shenanigans”:

“Doesn’t exist.”

That’s what is written on two Polaroids visible at Gagosian, of two undated works. “Doesn’t exist” is a koan, of sorts: the objects in the photo did exist at one point, a state that Polaroids are optimized to prove. And of course, the photo exists: at one point, the artist was flapping it in the air, and now you [or Octavio, I guess] are right there looking at it.

“Doesn’t exist” is a state that, unlike “Destroyed,” betrays no hint of action. But the paradox of a photo of something that doesn’t exist is resolved by time: The caption can only have been written—and non-existence declared—after the photo was taken. How long after, and what went down in between, it doesn’t say. Was it documentation of a work-in-progress, like the various positionings of the goat in Rauschenberg’s Monogram? An inventory made years later? We can’t know.

Were they even works? The declaration of non-existence makes it easier to assume so. Noland’s sculptures do exist in a specific constellation of found elements. And when those elements change, the work apparently changes, too.

It feels like a fool’s errand to try to track the dispersal of these items. So here I go: a folding bed frame like the one up top appears in Our American Cousin, a large assemblage Noland showed at American Fine Arts in 1989. That bed had a car bumper and other stuff on it, not flags and beer cans.

I thought the bent Ford license plate in the wall assemblage would be easy to spot if it was reused. Instead it is easy to see that it doesn’t turn up. The license plate frame on the right, though, does look like one that hangs on a much larger work, Shuttle (1987), which Noland showed in Rotterdam in 1988. [That work is now at Glenstone.]

These similarities only hint at time brackets, though; we know Noland was buying walkers and handcuffs in bulk, why not other objects, too? I guess the real question is not, is this the same flimsy bed, but maybe just, what happened to these things? Actually, the real question, at least for the guy who’s been chasing lost paintings and recreating destroyed artworks is, can they exist again?

Archival Polaroids [tumblr.com/octavio-world]