I was not prepared to be taken out a Jenny Holzer exhibition, especially since her most recent show at the Guggenheim seemed so lost. But that was then and there, and this is here—in DC, at Glenstone—and now—in the midst of a fascist crime spree by and against the government.

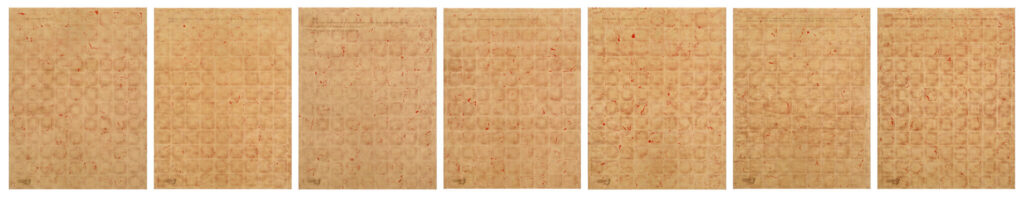

It was not the merch in the tiny book nook. It was not the entire gallery of redaction paintings—enlarged, oil-on-linen facsimiles of damning documents of the torture and atrocities of Bush’s Iraq war—though I really do wish this country would not give Holzer quite so much content to work with. Turns out abuse of power comes as no surprise because it happens over and over and over.

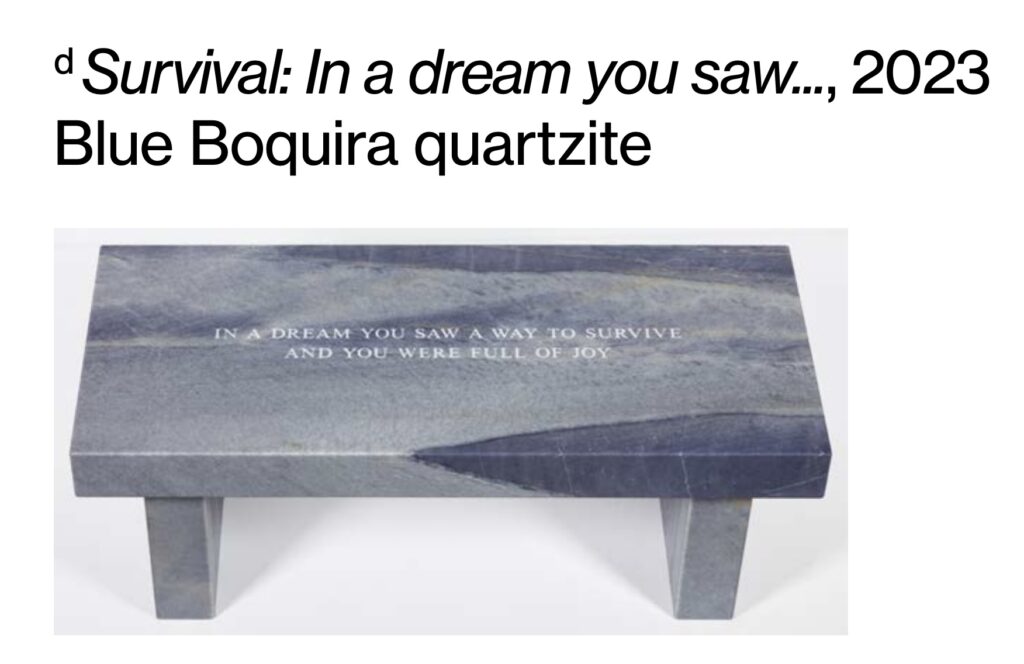

It was the next gallery of the private museum sanctuary, with the large window onto an artfully crafted vista, where Holzer crashed a tsunami of opulence over my unsuspecting head. It was all benches and paintings, not an LED ticker or a bumper sticker in sight. The benches in Blue sodalite. Bulgari Blue marble. Blue Boquira quartzite. Persian travertine and Silver Wave marble. Paintings large and small, single and in rows, cinnabar and lacquer finishes covered in copper and gold leaf, glowing in the morning sun. The extravagance of Holzer’s materials was so relentless, it was wretched. The polish, the weight, the preciousness, the hand, the logistics, the overpowering beauty impossible to ignore.

And to what end? The benches were engraved with Truisms we’re being forced to live through now. Each monochrome painting in stake in the heart (2024) contained a single line of text, terrifying exchanges sent to or from White House lackeys during the January 6th, 2021 insurrection. And on either end of the gallery, large paintings depicted—under the metal leaf, we’re told—either a portrait of Trump or a page of his book, entered into court as evidence for his multiple, felony fraud convictions.

When showing several of these works last year at the Guggenheim, Holzer said, “I wanted to show time and care. I wanted it to be an indicator of sincerity and attention. I wanted the works to be human.” Here at this precarious moment, the same works of extreme lavishness and expense definitely have my attention.

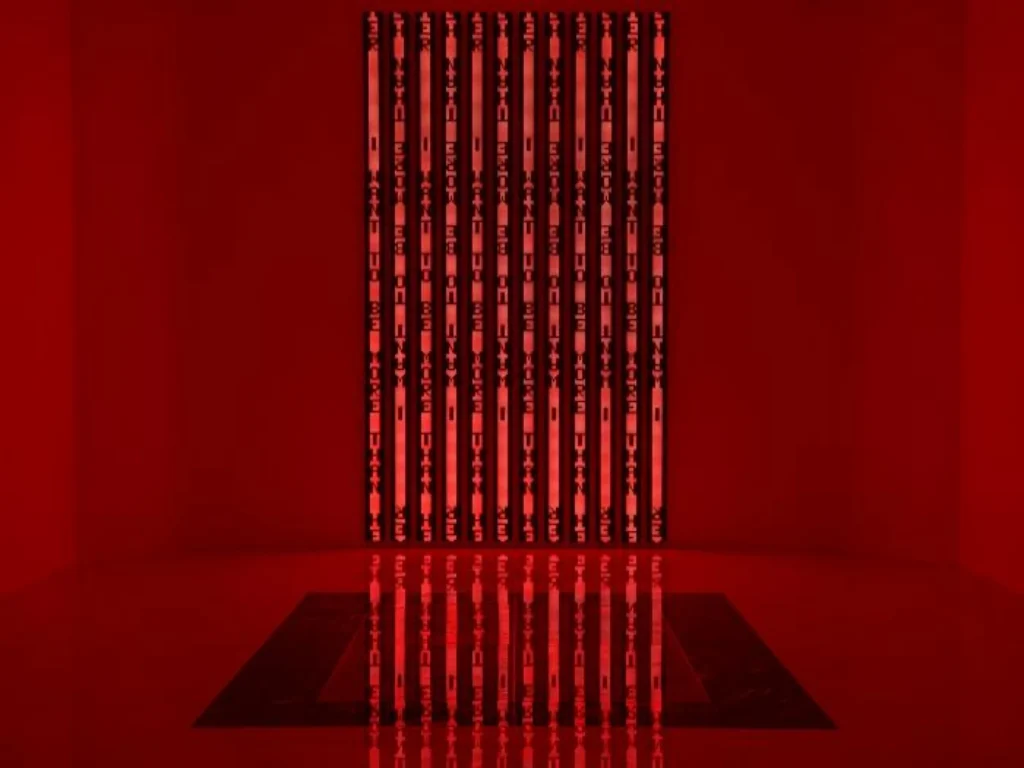

In writing about the problems of Holzer’s Guggenheim show, I flagged the complicated relationship with the LED ticker, which has become a full-fledged video screen. But two of the three LED installations at Glenstone predate this pivot to video flop era, and are fine. One, The Child Room, the marble and LED installation from Holzer’s 1990 Venice US Pavilion, is even great. But the unrestrained materiality of Holzer’s sculpture and painting yields an unthwartable beauty that she—leans into is too weak a phrase. She exults in it, and the attention it commands.

But so, importantly, does Glenstone. The terrible history and present that Holzer has aestheticized for urgent attention has been edited, collected, curated, realized, and exhibited in this singular context: a billionaire’s museum in an ongoing coup. As contemplative as the museum experience may be, the exhibition guide [pdf] includes unalloyed descriptions of every work, its reference—and links to the underlying court and FOIA documents.

Two restrained descriptions are the exceptions that prove the potency of Glenstone’s calibrated mediation. In the first gallery, the text on two engraved benches, excerpted from Arno (1996), is “a meditation on grief after a great and terrible love.” And in the final installation, The Child Room is simply, “a semi-autobiographical text in which a mother agonizes about protecting her newborn baby girl.” In both these cases, Holzer’s powerful texts unfurl and explain themselves as you encounter them. Though they’re each historic and somewhat specific, they both also felt viscerally of this terrible, agonizing moment we’re living in now. And Holzer and Glenstone know that.

I would love a world where authoritarians aren’t in power; criminals face accountability; and art is robustly supported by government for the public good. Instead we have the White House posting concentration camp tiktoks with a Rolex on the literal one hand, and Simone Leigh and Jenny Holzer following Cady Noland at Glenstone on the other.