In the Niebelungenlied, the dragon Fafnir lived in Drachenfels, a mountain towering above the Rhine. Siegfried killed him and became invulnerable by bathing in his blood. The poems of Byron and travelogues of Schlegel turned the Burg Drachenfels and other ruins of medieval castles along the peaks of the Rhine Gorge into Romantic tourist destinations, from which western culture has not recovered. Since 1883 a railway has taken tourists to the Burg Drachenfels, which once protected Cologne from southern invasion. Halfway up is the Niebelungenhalle, a shrine to Richard Wagner filled with Hermann Hendrich’s paintings of the Ring Cycle.

At the base of the railway, in the town of Königswinter, from the end of WWII until the rise of cellphone cameras, Richard Kern ran his family’s Schnellfotografie studio, taking instant souvenir photos for tourists. His 90th birthday last fall was the occasion for all of Germany to remember their childhood visits to Königswinter, when they sat on the donkey, and behind the cardboard plane.

In 2017 journalist Susanne Kippenberger recalled for Taggespiegel how her father, in relentless pursuit of joviality, organized their family life around holidays and vacations, all carefully documented. It’s part of a larger story, a family biography Kippenberger published in 2012, about her brother, Martin, and the German art world he overwhelmed during his intense, brief life.

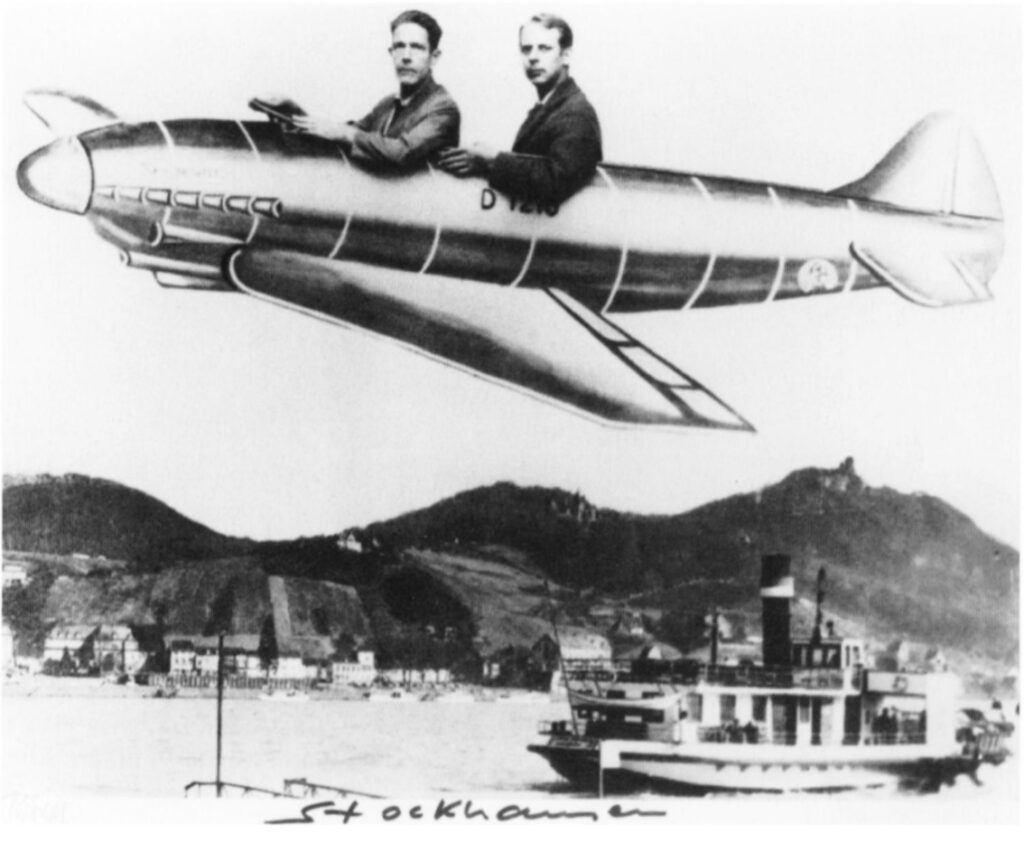

From the online collections of Schnellfotos, it’s clear Kern remade his painted plane prop regularly. The model of Junkers plane sometimes changed, but the outdated WWI-era registry number, D1214, remained, a signature of the family business.

It is remarkable to me that in the entire Wikipedia article for the German contemporary composer and champion of indeterminacy Karlheinz Stockhausen, John Cage is only mentioned once, and only then as a way to mark Stockhausen’s fame: “Stockhausen, along with John Cage, is one of the few avant-garde composers to have succeeded in penetrating the popular consciousness.”

Coming up in what turns out to be a John Cage bubble of New York/US primacy, all I ever really knew as a music non-professional was that Cage both burned the ships and lighted the way for the postwar European avant-garde by bringing the Cortésian-Promethean fire of indeterminacy to the Darmstadt New Music Courses in 1958. [Cage also used the $8,000 he won on a rigged Italian gameshow to buy a VW bus for Merce’s dance tours, but we’ve covered that before.]

I can see how Europeans might have had a different view. But even with years of focus on Cage’s European—and, specifically, German—projects, I had no idea of the ferocity of the Cage/Stockhausen and Cage/Boulez slapfights over the years. The many years. Nor the intensity of the critical rivalries over the origins and implications of chance and indeterminacy in music and art. Volume 82, published in Autumn 1997, was the third issue of October magazine devoted to sorting out Cage’s role in this important but underdocumented history of postwar culture.

Its curator/editor Ian Pepper had begun his “Cage report” in 1992, at the invitation of Rosalind Krauss. For his first issue, Vol. 65 in 1993, he brought in fresh publications of correspondence between Cage and Pierre Boulez from the critical moment where Cage shifted from his Schoenbergian atonality to the sound revolution of 4’33” and the compositional upheaval of chance operations. In 1997 he dug up and translated a chapter of the German critic Konrad Boehmer’s 1967 dissertation, titled “Chance as Ideology”, in which Stockhausen becomes collateral damage in Boehmer’s unrelenting critique of Cage:

Cage had the greatest success among composers of inferior quality, those who wanted to escape from the rigors of serial composition anyway, but who—obeying the fashion of the times—did not dare return to the neutral idiom of Neoclassicism. Through Cage, they not only justified the discovery of a dismaying simplicity in technical matters; they also legitimate these as “up-to-date” by means of handy philosophical props. And the lament that Cage has had a catastrophic effect on musical development, raised year after year in the press, is only a half-truth; equally so are the protests by individual composers that their aleatory conceptions were in no way influenced by Cage. In fact, composers of the first rank, such as Boulez, Nono, and Koenig, simply laughed at Cage’s philosophy, and one cannot suspect that they have after all secretly made it their own in their work. On the other hand, composers such as Stockhausen and Pousseur—however much they might personally deny it—have internalized the Cageian worldview with no benefit to their production. This is especially so in the case of Stockhausen, who until the Groups of Three Orchestras (1955-56) wrote work of the highest level; his submission to ideological forms of indeterminacy was followed by a drastic drop in compositional quality, now evident.

Again, 1967. Thirty whole years later, in his intro to October, Vol. 82, Pepper does point out the things Boehmer missed or got wrong in his evisceration of Cage. Most important is the larger artistic context in which Cage was operating. Still, I can see how someone coming from the putting and judging musical notes in order on a page industry, like Boehmer, might be upset.

I cannot, however, figure out how this 1958 photo of John Cage and Karlheinz Stockhausen came to be. Darmstadt is not close to Königswinter. They made a special trip. Cage had to have some idea of what lay ahead, but did he know about the Niebelungenhalle? There is no way he could have known about Richard Kern and his cardboard plane. But Stockhausen absolutely did. 100%. It was a set-up.

This photo is also blurrier, and cropped differently than the Kippenbergers’, and printed with a border big enough to write Stockhausen on. I think this souvenir photo was rephotographed and reproduced. Where did it circulate? Who was making copies?

Though his hate game was strong enough in both directions, Boehmer did not include the photo in Zur Theorie der offenen Form in der neuen Musik, the published version of his dissertation. So putting it into October was a choice. [Looks at Ian Pepper and Rosalind Krauss]

I have no choice now but to continue my search by ordering Stockhausen Serves Imperialism Cornelius Cardew’s 1974 Marxist critique of both Stockhausen and Cage, which I missed when Primary Information republished it in March 2020.