In 1995 Larry Rinder and Nayland Blake organized In A Different Light, one of the first exhibitions of 20th century art exploring the queer experience, at the Berkeley Art Museum.

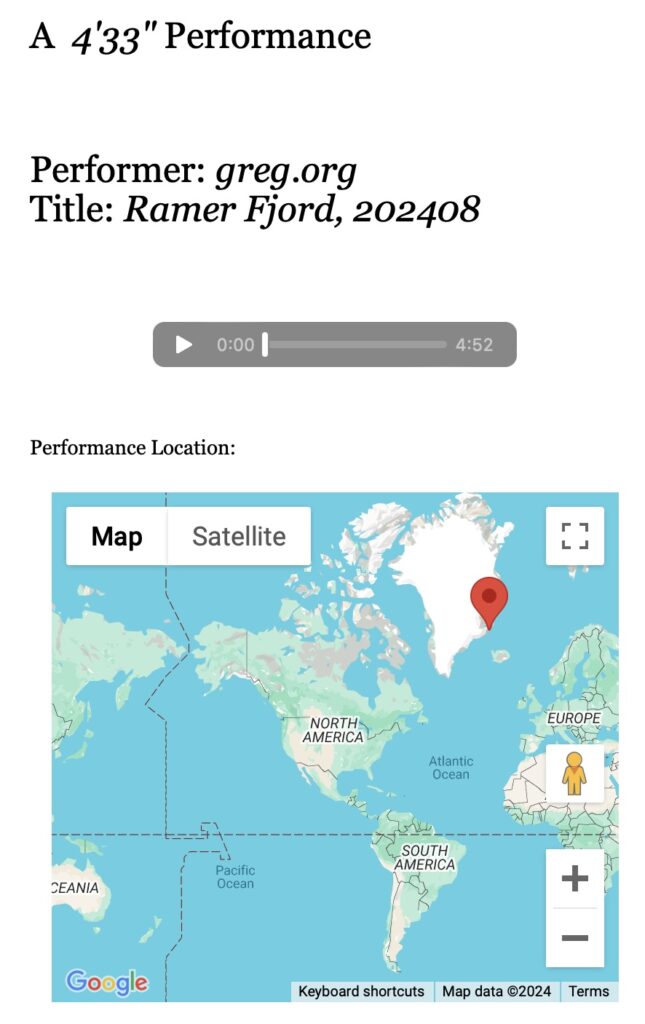

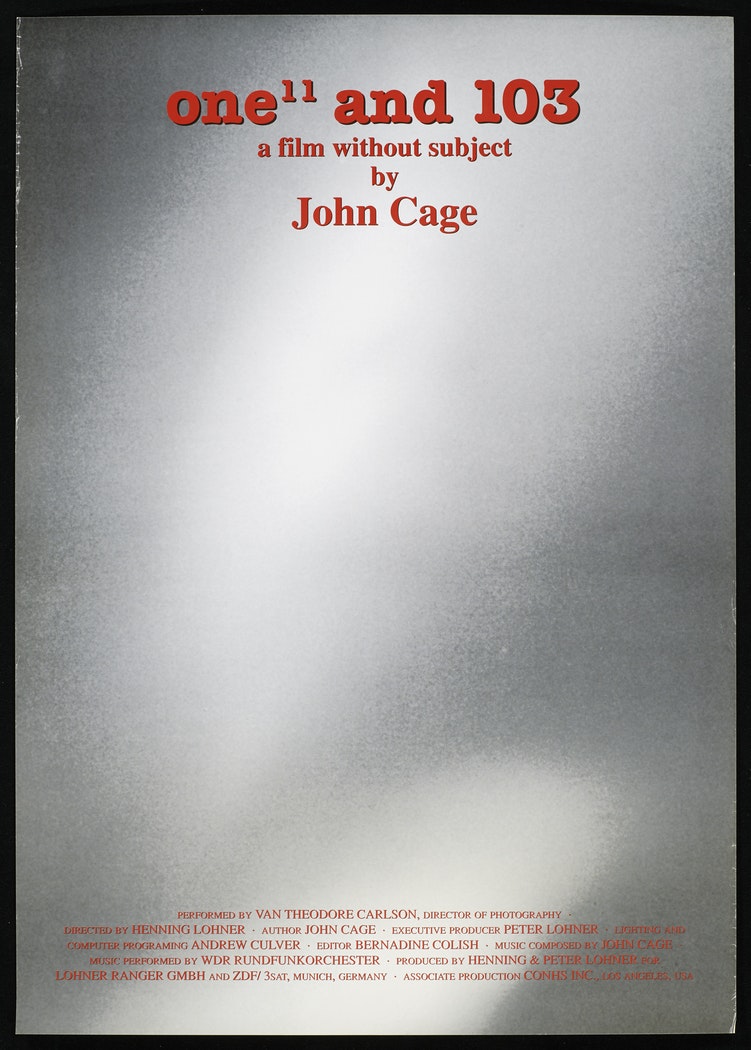

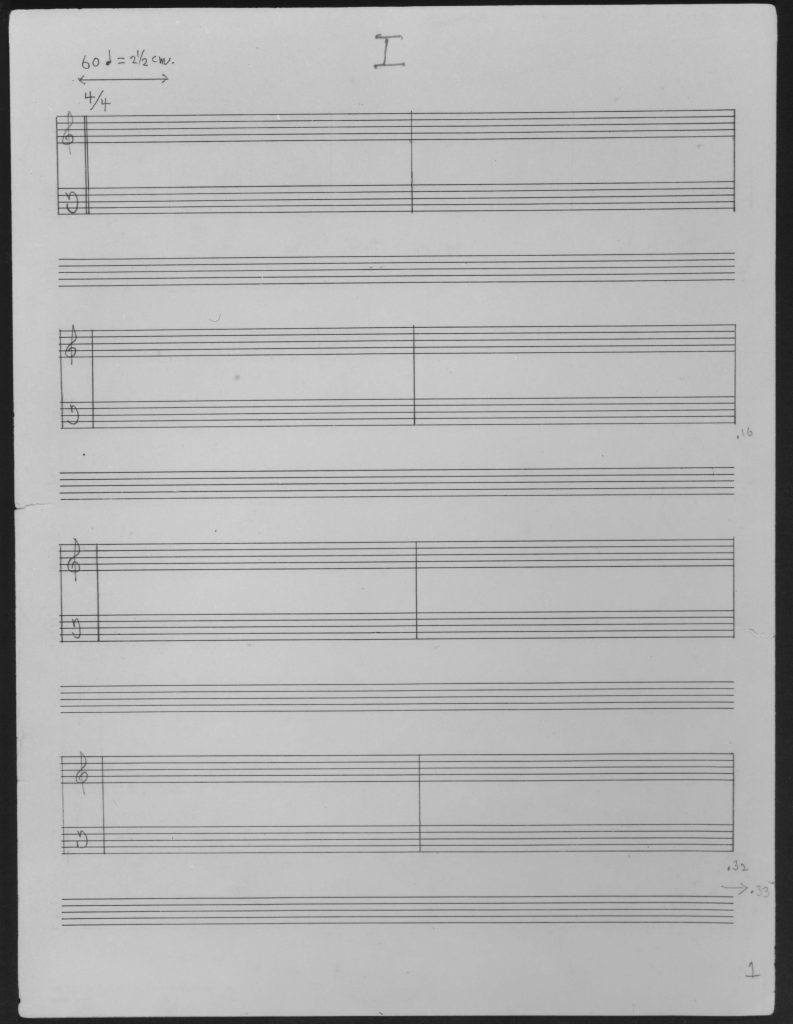

The first section of the show was “Void,” with works “suggesting blankness, absence, and loss.” And the first work on the checklist—which I uploaded to the Internet Archive because it was somehow not there before—is David Tudor’s 1989 reconstruction of the score for John Cage’s 4’33”.

It’s one of the works which “suggest the emptiness of what might be called a state of ‘pre- being’ that precedes the birth of a new identity. Seen negatively, such works evoke the repressive alienation of the ‘closet.’ Seen in a more positive light, they represent a blank slate of unlimited possibility.”

Cage’s original score for 4’33” was dedicated to Tudor, who performed it in 1952. It was made in traditional Western musical notation, with a tempo and length to indicate the duration of each of the work’s three movements. Tudor gave the score back to Johns when he was preparing another copy, this time in graphic notation, which he dedicated to Irwin Kremen. Then Tudor’s copy was lost, and so Kremen’s copy, from 1953 is the earliest surviving score. David Platzker acquired it for MoMA in 2012.

Larry Solomon’s 1998 essay on the history of 4’33” does a pretty good job of tracking Cage’s various editions, but not Tudor’s. James Pritchett’s website is a clearer exploration of 4’33” and its origins, and related works.

Tudor’s reconstruction of the original 4’33” score seems related to the differences introduced in published versions. It measured 60 quarter notes at 4/4 time to be 2.5 cm, or roughly 1 inch of score, so the first 32 seconds of the 33 second movement fit on one 9.3-inch wide page. I think that makes Tudor’s score ten pages long. [Somehow Edition Peters needed the Getty’s help to recover this reconstruction for inclusion in the current, Cage Centennial edition of 4’33”. And they still reduced the page size and mooted Tudor’s calculations.]

In their discussion of the show in for their AAA oral history, recorded in 2016, Blake recalls various aspects of the show, and mentions “Void” also containing a piece by Bay Area artist “Rudy Lemcke who had erased a—John Cage’s score for 4’33″.

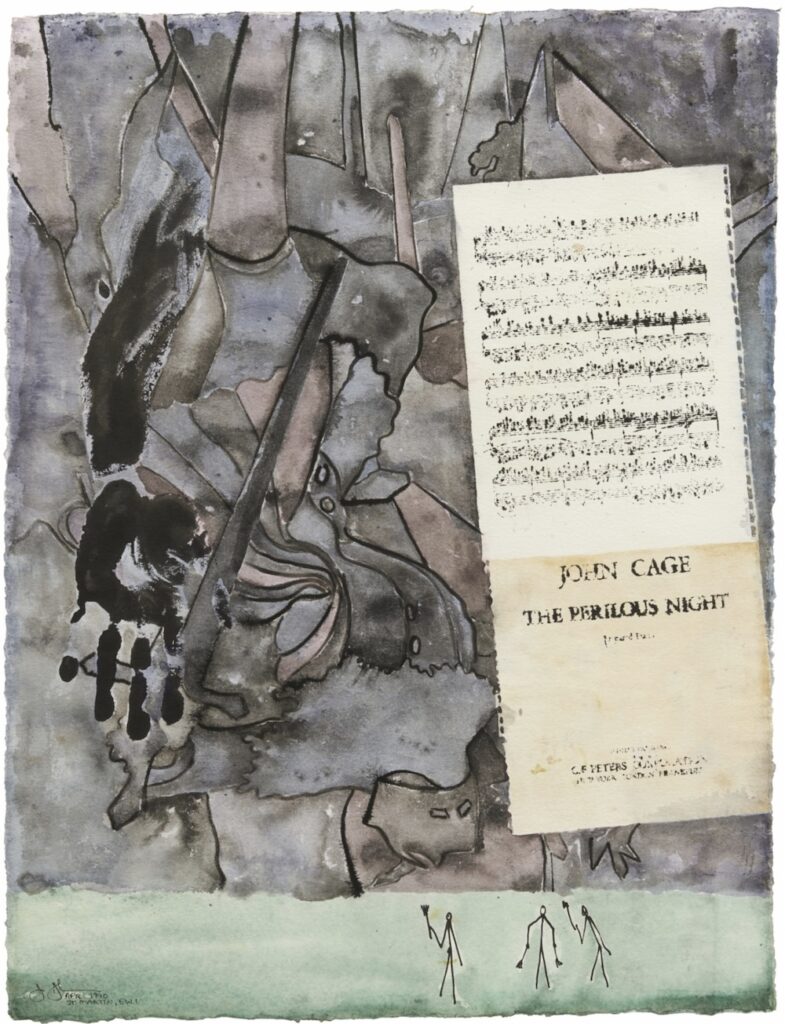

Lemcke has made a lot of Cage-inspired work, particularly in Cage’s chance-operations texts and mesostic poems, but also involving the score of Perilous Night (1944), Cage’s pivotal chance-related composition for prepared piano, which also coincided with Cage’s pivot from his wife Xenia to Merce Cunningham. But I can’t find any mention of Lemcke doing an erased Cage score. And Lemcke’s work on the exhibition checklist, right next to Tudor’s, is Untitled (Performance Score for Percussion), 1977, which sounds related to a different series Lemcke was working on over several years.

I’ve reached out to confirm, but if an Erased Cage Score doesn’t exist already, it must be realized immediately, because it sounds absolutely obvious and fantastic. [a few minutes later update] Lemcke confirms that though Cage was an influence on his early work, and particularly his exploration of chance operations and graphic notation, the work shown at Berkeley was not 4’33” related, and he has not erased a Cage score. So now I will.

It would complete the circle, or perhaps spiral outward, from Rauschenberg’s early influence on Cage, who felt the White Paintings of 1951 gave him permission to write “the silent piece” he’d been contemplating for several years already. And the painting Rauschenberg gave to Cage, which he then overpainted black when he was crashing at Cage’s apartment.

From a more limited vantage point, this could have been seen as Blake misremembering, when it is clear that artist prophets walk among us, and they were manifesting Erased Cage Score into being. It should not have taken this long.