Usually the Internet solves mysteries by yielding definitive information. Sometimes it makes it worse, though, and more confusing. Tumblr, I’m lookin’ at you.

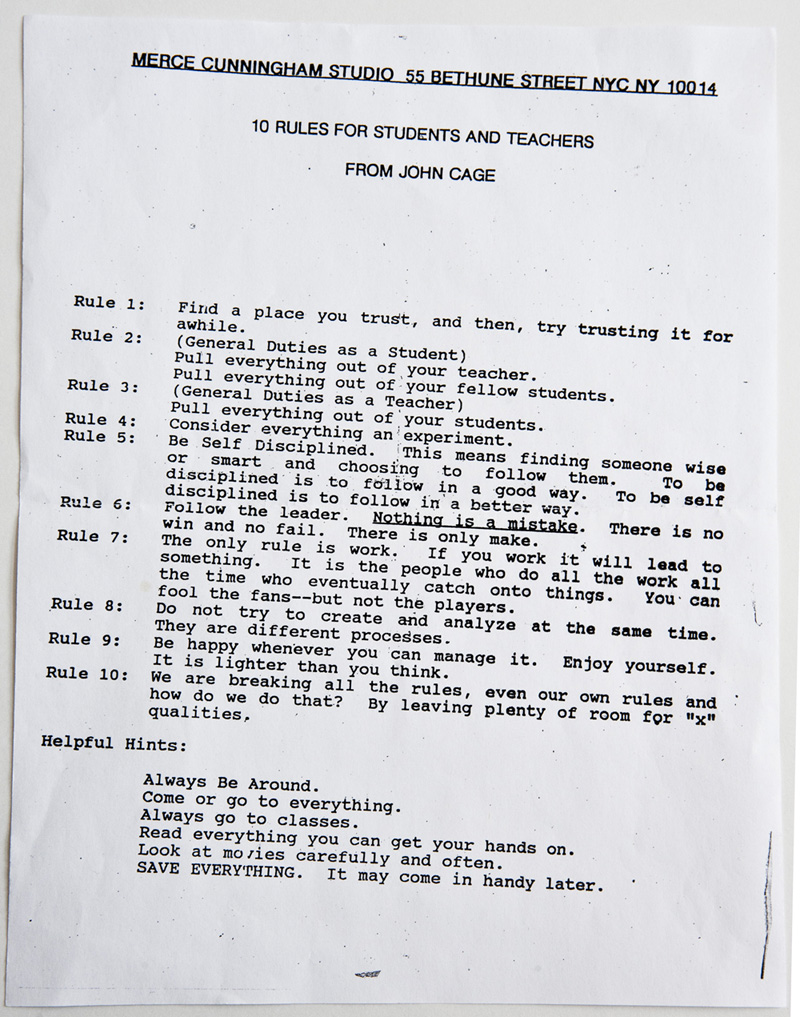

Artist/artist book hero Dave Dyment emailed the other day, wondering what I thought about the source of 10 Rules For Students And Teachers From John Cage, which was famously on the wall at Merce Cunningham’s studio for years, and which has been circulating online in various photocopied and scanned forms.

Except for Rule 10, which is a quote from Cage’s book SILENCE, Dave didn’t think it really sounded like Cage, and I certainly agree. And he’d never been able to find the other texts in Cage’s published works. So who might have written it, if not Cage? And if he didn’t write it, how did it get attributed to Cage, while it was hanging on the wall of Cage’s longtime partner’s studio?

In 2012, Brain Picking had said that despite what everyone thought about Cage, 10 Rules’ actual author was everyone’s favorite serigraphicist nun, Sister Corita Kent.

Which was funny, because in 2010, blogger Keri Smith wrote about 10 Rules [update: 2014 Internet Archive version] because she’d heard exactly the opposite: that despite what everyone had heard about Sister Corita, those rules were actually written by John Cage. And one source of that information was none other than Laura Kuhn, of the John Cage Trust.

Smith’s post attracted some seriously high quality comments in 2010-12, including students of students of Sister Corita who remembered the Rules; and scholars of dancers who remembered the flyers. Then in June 2012, Jill Bell quoted “Richard Crawford who was in on the creation of ‘The Rules’.” Crawford was a student of Sister Corita’s in 1967-68, and says she gave the class the assignment to come up with a list of rules one night, and then to design and print them up. Cage’s quote was contributed by one of the students.

Which, even if it’s definitive, still doesn’t explain how they got to Cage, and to Merce with Cage’s name. The Rules circulated among Kent’s students and school. They were included in the 1986 edition of the Whole Earth Catalog, with Cage’s name in parentheses following Rule 10. Whether Kent sent the Rules to Cage before this, or after, or Cage found them and posted them, or a Merce dancer found them, they were connected to Cage and had a resonant presence in Cunningham’s and Cage’s community. If the last two years have uncovered any additional history from the MCDC side, I haven’t seen it, but I’d love to.

2012: 10 Rules for Students, Teachers, and Life by John Cage and Sister Corita Kent [brainpickings.org]

2010: You Know I Love A Good Mystery [kerismith]

Tag: john cage

The VW Years: Virginia Dwan Edition

Oh-ho, here is an awesome entry for The VW Years, greg.org’s ongoing mission to collect firsthand accounts of John Cage and Merce Cunningham’s VW Bus. The idea comes from the title of a chapter in dancer Carolyn Brown’s fascinating memoir, Chance and Circumstance: Twenty Years With Cage And Cunningham.

But this account’s from art dealer Virginia Dwan, in Artforum’s 500 Words, as told to Lauren O’Neill-Butler:

In New York, I became very interested in and involved with Minimalism and gave solo shows to Sol LeWitt and Carl Andre, and later Robert Smithson. When I moved the gallery to West Fifty-Seventh Street, I didn’t have enough space for them to do very large works, so I kept the gallery in Los Angeles with my assistant John Weber still working there, and I sent the artists out there to put up their shows. A favorite memory was when Merce Cunningham, John Cage, David Tudor, and Robert Rauschenberg drove from New York in a Volkswagen bus for one of Robert’s shows. They parked it in front of my house in Malibu and out of this bus came nine people. It was like a circus bus with endless people emerging. They had all driven from New York to Los Angeles and stopped along the way giving performances. I didn’t know how they all fit, yet there they all were in the bus.

The Robert she’s referring to has to be Rauschenberg, not Smithson. And it looks like Rauschenberg showed twice at Dwan’s Los Angeles gallery, in 1962, and 1965. The first show corresponds to what Brown called “the golden years” of touring, which ended in June 1964, when Rauschenberg won the Venice Bienale during the company’s tour of Japan, and it became a problem, and there was a messy split, so the idea of all these now-celebrities piling back into a VW bus and dance-busking their way to Bob’s show seems, at the very least, improbable.

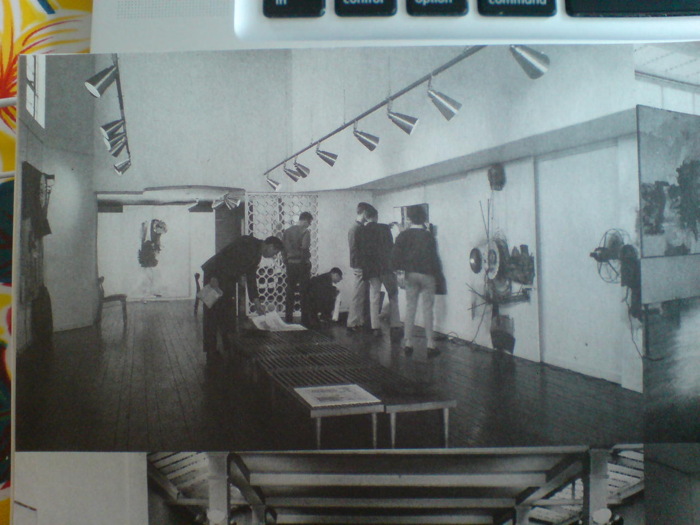

So it was 1962, before Dwan’s New York gallery, and in her first LA space. Rauschenberg’s show ran March 4-31. The Dwan Archives at the Smithsonian give the title, “Drawings,” but there’s a little installation photo in Terry Schimmel’s Combines catalogue [above] that clearly shows Combines. From left: First Landing Jump (1961); Blue Eagle (1961); Black Market (1961); Navigator (1962); and Pantomime (1961). [Schimmel’s appendix note that Co-existence (1961), Rigger (1961) and Wooden Gallop (1962) were also in the show.]

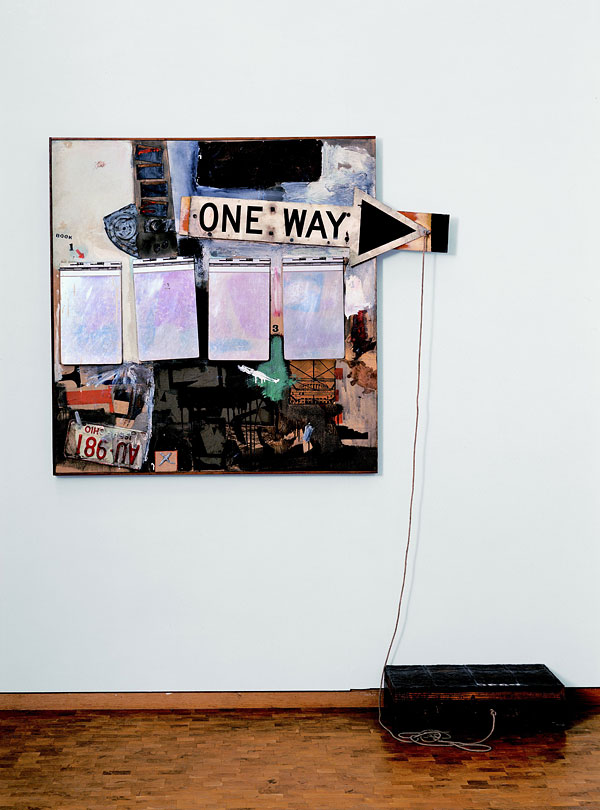

Robert Rauschenberg, Black Market, 1961, collection Ludwig Museum, Cologne

Black Market is an amazing and important work, and one that relates directly to another ongoing greg.org topic: Short Circuit and Jasper Johns’ Flag. Black Market contains a valise on the floor with various items and diagrams from Rauschenberg which viewers would exchange for a personally valuable item of their own. There’s a little Rauschenberg stamp pad, too, so everything you put in would be(come) a Rauschenberg. Think about that for a while.

It was first viewed in 1961 at the Stedelijk, and had its US debut at Dwan. There’s a lot more going on with this work, but it’s already too tangential for words right now. Suffice it to say, Jasper Johns was not on the bus.

Virginia Dwan | 500 Words, fortunately part 1 of 2 [artforum]

Previously:

The VW Years: Ch. 1 – 1957 – The Italian gameshow mushroom boondoggle

Ch. 2 1956-62 – Remy Charlip & Steve Paxton

Ch. 3 – John Cage

Carolyn Brown, Part I

Carolyn Brown, Part II, the real inspiration

The VW Appears: a snapshot from the John Cage Trust

The VW Years: Appendix: Living Theatre

The Annotated Charlotte Moorman Answering Machine Tapes

So like you, I’m sure, I was baffled and amused listening to avant-garde cellist and frequent Nam June Paik collaborator Charlotte Moorman’s answering machine recording on Ubu.

It takes a minute to get your bearings, and then you realize it really is John Lennon complaining about a review in the Village Voice by “a couple of bastards, whoever they are,” and also mentioning an ad Yoko placed in the same issue.

And then there’s a spitting mad John Cage demanding Charlotte or Howard Wise write a letter to the Village Voice “protesting Fred McDarrah’s censorship of my name from that article, or I’m never doing anything for you or anybody else ever again,” which, hello, what?

What had Cage been so ignominiously ignored in? It wasn’t even clear what year the tape was from, though Moorman’s callers mention Thanksgiving [and the recording title says Nov. 24 – Dec. 6]. If Howard Wise was mentioned, perhaps it was Moorman’s performance of a Cage composition at the gallery.

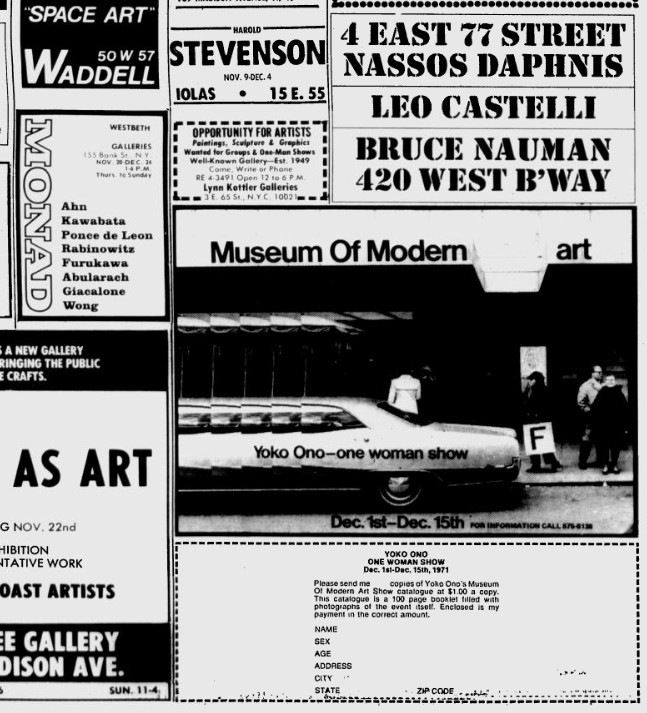

Well, stop worrying, because Lennon’s reference to Ono’s ad means it’s 1971, when Ono advertised her own One Woman Show at The Museum of Modern Art, and its accompanying catalogue, even though the museum was not on board with it.

Ono hired a guy with a sandwich board to walk around in front of the Modern for two weeks, Dec. 1-15, advertising a show that was technically not inside. [Though it confused enough people, apparently, that the membership desk put a little sign up, with Ono’s ad, saying “This is not here,” which was, by so doing, no longer true.] Anyway, the citation given for Ono’s Voice ad is usually Dec. 2, 1971. And the ad does run in that issue.

But the version Lennon was calling Moorman about, “on page 31,” was actually from the week prior, Nov. 25. It’s up top, reproduced, I believe, for the first time online, not counting Google’s still unindexed archive of the Village Voice. NBD.

Which is where Fred McDurrah’s article is found, too. It was a report from Moorman’s 8th Annual Avant Garde Festival, a roving project that infuriated and entertained the small New York art world with impressive regularity. 1971’s version was held in the 69th Regiment Armory, and was backed by Barbara & Howard Wise. McDarrah’s ostentatiously jaded account was meant to disparage the multi-media, performative, absurdist circus, but he actually makes it sound kind of interesting. Or maybe reading about it now, during Frieze Week, it just seems normal.

McDarrah writes that Moorman secured the Armory by promising “the Colonel in charge” that there would be “no nudes, no sex, no politics, no dope, no nothing.” Not all of her artist invitees seem to have gotten the message.

I looked at my watch and decided it was time to ask the soldiers the standard “what-do-you-think-of-this-stuff question…A veteran of all the wars who was covered with stars, badges, ribbons, buttons, and braid summarized his feelings: “It’s ridiculous, stupid, the whole damn thing. All those people smoking marijuana back there. I saw them. And using a federal building too. A bunch of kooks. I could bow them bastards to hell. I’d go up in the balcony with a machine gun. I even saw some naked. I’m glad I’m being transferred out.”

Yow, OK then. Did New York’s know how close it came to starring in an art world-meets-Kent State-themed prequel of Inglourious Basterds?

Anyway, sure enough, Cage isn’t mentioned anywhere. Though he’s probably glad to have missed the near massacre. In another, later message on Moorman’s machine, a calmer, more sheepish Cage apologies for not attending a big event, so I’m going to guess that it was Cage’s composition, not his presence, that was snubbed. Unless it was Cage who McDarrah called Moorman about; he left his own message when he heard he’d misidentified someone sitting “cross-legged in the corner and mix[ing] his ‘ohms’ into the abysmal hum and drone of 1000 sounds” as Steve Reich.

And it turns out all I had to do was look a little further. Because computer artist Fred Stern, who did get namechecked in the Voice article, turned Moorman’s recording into a slideshow, synced with clippings and snapshots. Very helpful.

Charlotte Moorman’s Answering Machine Message Tape [youtube]

Scoring John Cage’s Table

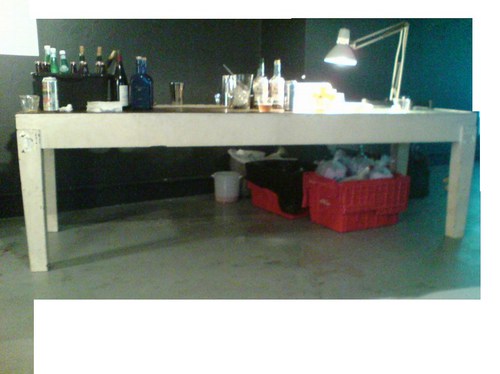

So this is John Cage’s table.

Nothing fuels one’s quixotic pursuit of Cage’s visual and aesthetic artifacts quite like being served a drink from what turns out to be John Cage’s table.

I cannot say where or when I saw it. I cannot say who has it. I can only say I was told that it was Cage’s table–really, John’s and Merce’s table–from their loft on 18th St, and that it came with instructions [conditions?] not to fetishize it. I believe that was the word used. Maybe it was valorize. Not to valorize it. At which point I joked that I did not fetishize it or whatever, I only coveted it. And I promised that, if asked, I would attest that it was not fetishized, and that if it was given to me, I would not fetishize it, either.

Upon reflection, it felt like a useful insight into Cage’s perception of objects, the things around him which he knew, if he wanted or allowed them to, could garner attention or importance by virtue of being his. It’s Buddhism 101, eschewing attachment to objects, but it’s also an artistic position. No branding. At the very least, art was not a practice for generating objects, either for sale or veneration. Oh, maybe that’s what it was not supposed be: venerated.

Yes, that’s it. Veneration. Like saints and gurus. I could see why Cage would be sensitive to that. No problem. Since it was being used as a sloppy drinks table, I was going to happily attest that it was not being venerated in the slightest. No venerating here, nosiree.

But let’s just take a look at it instead, hmm? Because it does have some aspects which we might consider Cageian. It’s rough, simple, not fancy, not precious, not worked, just made. It’s painted white, like the original Mazza loft. It’s utilitarian, or functional. Multi-functional. IT HAS A LIGHT BOX BUILT RIGHT INTO THE END, PEOPLE. So it was for working, meeting, and eating.

And it was made, not bought, found, or adapted. With some trace of intention. No chance operation produced the slight taper in those square wooden legs. And there’s the nice little setback edge between the upper and lower halves.

Since the table was not immediately offered to me, and given its principled/conceptual encumbrances, the obvious thing was to make one myself. Which is why these photos exist, as documentation for this project, my second table. Table-shaped object. By-product of my performance of a score for a table. I really just want the table, mkay? I’m imperfect and unenlightened, and the Dalai Lama has his watch, I just want the table.

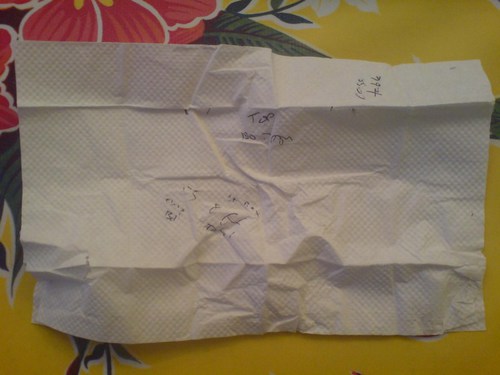

So as best I could, I took some measurements. I just found the napkin I used to scribble down some ad hoc data. What a dork I was right then and there. I hope I was at least amusing.

“Cage table”

those are the widths of the top and bottom of the legs, looks like about a 4/3, 1″ taper.

“55 [?] chip Bd?

lt Box 8 ft Total”

That can’t be right. Well, it’s close. If the napkin’s 10″, the light box looks to be around 3′, at least. [That was my unit of measure: napkinlengths.] I guess I figured I’d be able to feasibly extrapolate the other dimensions? Was that what I was thinking?

Hmm, maybe this was found, and hacked. Given a new top and a paint job. An old lab table or something. Because seriously, those legs are non-trivial. But then, those legs also look hammered. I won’t fetishize or historicize the construction. Any deskilling will be my own.

Meanwhile, seriously, current non-venerator[s] of this table, if it’s ever in the way, or under threat, or if you redecorate, or whatever, any reason, let me know, and I’ll gladly clear it out in the least venerating way possible.

Satie Society Photomurals

It’s been a while since I had a good old-fashioned photomuralling around here, and this one comes from an unexpected source: John Cage. Mostly.

I’d seen installation photos before of MAC Lyon’s Cage’s Satie: Composition for Museum , an exhibition curated by Laura Kuhn from the John Cage Trust. The show includes several composition-related installations, and a gallery dedicated to The First Meeting of the Satie Society, (1985-1992),

Cage’s stunning late-life collaborative merger of poetry, performance, visual art, sculpture, and music. This work was conceived as a collection of “presents” for Erik Satie, an invitation by John Cage to his esteemed artist friends to fill a Marcel Duchamp-inspired cracked glass valise with words and images bound into eight hand made books. Contributors in the visual aspects include Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Sol LeWitt, Robert Ryman, and Cage himself.

[I wrote about this Satie-inspired project last year.]

But it wasn’t until Alex Ross posted the top image that I realized what these giant wall pieces were: they’re large-scale photos of close-ups of various texts imprinted on the steel Satie Society valise. That’s the title, obviously. Here’s another, “Some artists apparently want to be buried alive.” which, hmm. I can’t find any mention of the quote online, but given that it’s incised on an indeterminate handful of mostly unpublished metal boxes scattered to the collecting winds, I guess that’s not a surprise.

What is a bit surprising, though, is the visual boldness of the photos, which really dominate an otherwise spare, small-scale show in a vast space. As nice as they look, I guess they’re an exhibition design, not things. Except, of course, that they are.

There’s this atypical situation that I keep coming back to, the objects and artifacts of Cage. Things that, if he’d had a more materialist view of art, we might be able to consider from the perspective of art, if not to actually call them art objects.

This awkwardness is reinforced in a way by the surprisingly traditionalist view of artmaking that Cage held onto, at least for himself. However experimental or avant-garde his process–feather paintings, smoke drawings, a few prints, even this slightly affected Duchamp-related valise–the results were modest and old-school.

I guess I’m wondering, fantasizing, plotting, for a more interesting way to be a Cage collector when the available works, such as they are, are not that compelling. So I have questions about them, yes, but I also find these giant photo mural prints kind of sexy.

‘But Which One Of Us Drove The Car?’

In the Fall of 1953, Robert Rauschenberg and John Cage, fast friends and mutual admirers from Black Mountain, collaborated on an artwork. Cage had already been studying with DT Suzuki and had been discussing Zen in great depth with Rauschenberg. Which dialogue had led, the summer before at Black Mountain, Rauschenberg to make his White Paintings, and to Cage and others to orchestrate Theater Piece No. 1 and to compose 4’33”. Rauschenberg had already stayed at Cage’s loft while his new Fulton St. studio was being fumigated, where he’d surprised Cage by painting the painting Cage got from Rauschenberg’s 1951 show at Betty Parsons completely black.

Untitled (John Cage, Black Mountain), 1952, photo: Robert Rauschenberg

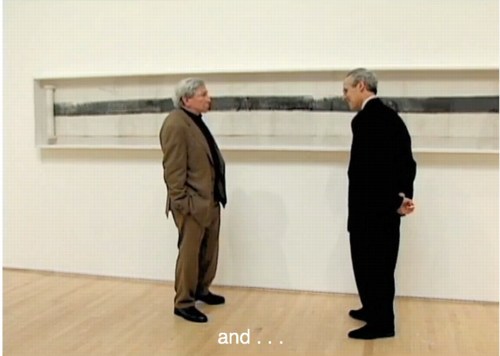

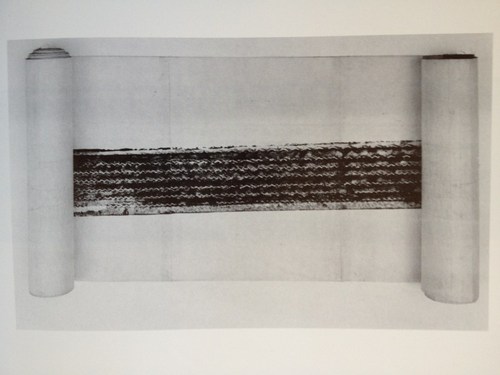

For the work that came to be known as Automobile Tire Print, Rauschenberg pasted 20 sheets of drawing paper into a scroll, which he laid down on an empty Fulton St one Sunday, and he inked the rear tire while Cage drove his Model A in a straight line along the paper. [Cage drove the Model A to Black Mountain, above. Apparently, Kaprow had a Model A, too.]

Michael Kimmelman is fond of noticing the similarity between the long, lone mark made by moving through space and Barnett Newman’s “zips,” which Rauschenberg would have seen at Parsons’ gallery in 1951 and 1952.

In the catalogue for his 1991 show Rauschenberg in the 50s,, Walter Hopps links Automobile Tire Print in time, medium, and concept to another major collaborative work on paper, Erased de Kooning Drawing. It turns out that for the first decade-plus after their creation, neither work was exhibited publicly, and both were known largely by word of mouth. They were discussed without being seen; as the product–or to use Harold Rosenberg’s influential 1952 term, the “residue”–of process, their physical state was secondary. Which let Hopps and others interpret and present them as precursors of Conceptual Art once such a thing came into existence.

Hopps says that Automobile Tire Print was “maintained as a scroll” which was eventually mounted on fabric for preservation. Since it was first exhibited in the 70s [and yes, I guess I’ll have to start digging into this history now, too], the work has been unfurled to various lengths. [Above, from Hopps’ 1976 show at the Smithsonian] Since Hopps, and definitely since SFMOMA’s acquisition of the piece in 1998, it has been completely unfurled.

The accounts, even the descriptions of the work, vary. Hopps said it’s ink. Rauschenberg said it was “house paint,” like the black paint he was using at the time on his Black Paintings. And that he poured it out on the street in front of Cage’s tire.

In that SFMOMA video, Bob told David Ross that he asked his friend to help execute his idea. Cage “was the printer,” Ross suggested, “the printer and the press,” said the artist. Without entirely contradicting that view, Cage wrote in 1961 in Silence, “I know he put the paint on the tires. And he unrolled the paper on the city street. But which one of us drove the car?”

Perhaps ambiguous authorship is just one more way Automobile Tire Print is like Erased deKooning Drawing, a work in which the central, conceptually transformational contribution of Jasper Johns had been willfully omitted for more than four decades.

Not that these questions of credit and origin give BMW any cover at all on their mindblowing direct marketing campaign “marking the momentous occasion” of the 40th anniversary of the M Motorsports car series.

The company that regularly puts artists in the promotional driver’s seat on its Art Car series completely fails to mention either Rauschenberg or Cage in the video for the M Print project, which is essentially a cover version, or a re-performance, of Automobile Tire Print starring the M6 sports coupe. The resulting prints were then cut into postcard size, and sent to new and prospective owners.

[FWIW, BMW also blanked a living artist, using the donut-spinning M6 (below) to re-enact Greeting Card, Aaron Young’s 2007 Park Avenue Armory motorcycle tire painting project. I’m sure if there were another car-related performance art project ransackable enough, BMW’s agency would have turned that one into postcards, too.]

I guess it’s possible to look at this as a glass half full situation, that the indexical Zen performative aesthetic of Cage & Rauschenberg has, sixty years later, gone mainstream. Or at least turned into a PR stunt to sell $100,000 sports cars.

The only way this ends well is if it spawns a cars-meets-Fluxus fauxreality TV show on the History Channel. John and Bob would surely be delighted.

The BMW M6 Creates Its Own Direct Mail [fastcocreate.com]

BMW M Presents: The Making of an M Print [youtube]

Previously, unexpectedly related: greg.org coverage of John Cage’s VW bus and of

the unexamined making of Erased de Kooning Drawing

John Cage’s Europeras 1 & 2, On Stage Now At The Ruhr Triennial

I’m done waiting. This Europera 1 & 2 post is apparently not going to write itself.

The Ruhr Triennial opened last weekend with what is only the third [production and fourth -ed.] staging of John Cage’s grandest* composition, the 1987 Europeras 1 & 2. It’s basically a chance operations tour de force that runs the entirety of the European opera canon–arias, stories, costumes, props, sets, lighting, libretti, staging, orchestra–through the I Ching wringer, which performance is conducted, so to speak, by the cues of a 2.75-hour clock. As Cage put it, “For 200 years the Europeans have sent us their operas. Now I’m returning all of them.”

All six performances in the Triennial’s home venue, the vast, repurposed industrial Centennial Hall Bochum sold out immediately. So far three have happened, directed by the director of the entire Triennial, avant-garde composer Heiner Goebbels.

So I’ve been monitoring the reviews jealously, and with some indignation. The scale and ambition and significance of the work is being respected—the work has only ever been performed in Germany [update below: not true]—but it seems that both critics and directors alike still struggle with the vocabulary and the very concept of Cage’s chance-driven work.

In the only English-language review I’ve found so far, The Financial Times’ Shirley Apthorp describes Europeras’ “extravagant evening of associative nonsense” as both “chaos” and “minutely choreographed absurdity.” Writing for FAZ Eleonore Buening criticized Goebbels for putting the “chaos Cage conceived a quarter century ago back in a Museumsvitrine.” If I read my German correctly, “The director placed too little confidence,” Buening writes, “in the expiration of the clock, the will of the participants, or even Comrade Chance.” And did Cage ever have a better comrade?

I have never seen Europera 1 & 2, but I’ve been studying up on them for the last year or so. The original staging, commissioned in 1985 by the Frankfurt Opera, was the dissertation subject of Laura Kuhn, who was involved in the production, and who has since become the director of the John Cage Trust.

Europera 1 & 2 strikes me as a simultaneous negation and celebration of opera as an art/theatrical form, but also as a cultural and historical institution. His chance-based composition removes narrative, character arcs, literary and stage conventions, and authorial intentions from the experience of a performance. Chance is not chaos or absurdity; it’s a different syntax. How does any opera performance seem if you don’t know the story or speak the language? Would you ever call it chaos or nonsense?

An opera diehard may want to identify the source of every passing prop, aria, or orchestral passage in Europera—did the Stump The Operahead trivia quiz during the intermission of the Met’s weekly radio broadcast ever tackle Cage? Just like a moviehound might try to flag the source of every clip in Christian Marclay’s The Clock. But that risks missing Cage’s point [which is not Marclay’s]: that the experience of the montage has quality and meaning and value in itself, apart from the original content and its juxtapositions, not because of them.

And maybe critics actually are better attuned to this now, and the problem [sic] is just/still the directors. In FAZ, discussing the “Children’s Jury” who Goebbels convened to award unconventional prizes during the Triennial, Buening found a new twist on the classic MTV Crisis when she worried that the media-saturated, “Multi-tasken” Kids These Days might be bored by Cage’s 1980s jump cut revolution. After watching a rehearsal of Europera Ruhr Nachtrichten writer Julia Gass said Cage foreshadowed the “TV Zapp Era”; actually, he was soaking in it. Cage’s vision of the future was surfing the 400 operatic channels of the past.

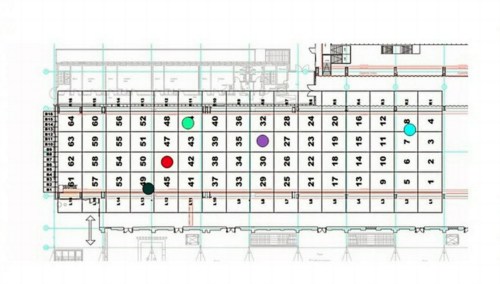

Europera may be Cage’s most ambitious and explicit appropriationist work. According to Kuhn’s firsthand account of the making of, Cage, relying on the collection of Lincoln Center’s library, determined to include only operas that were in the public domain. For the flats and sets, he had researchers in Germany compile engravings and illustrations of composers, architecture, and animals from pre-20th century books. With these copyright-free source sets established, Cage used chance operations and a time log to generate the content of the opera.

And this, apparently, is where Goebbels’ otherwise extraordinary production falls short. I’ll try to account for the differences—or more precisely, the changes—between Goebbels’ version and Cage’s, the immediately apparent one is his replacement of simple, graphic flats with actual operatic sets. Buening sees this as too deterministic, too willfully absurdist [in the mold of Robert Wilson, who, inexplicably, is the Triennial’s English talking head for Europera], and stuck to the cliches and one-liners of operatic theatricality. And too much of the director’s own indulgences, which runs diametrically counter to Cage’s purging intentions.

It’s a perennial problem with Cage’s interpreters, who take the indeterminacy of his compositions as license to do whatever they want. Not coincidentally, that sounds like exactly the criticism voiced in OMM by Sebastian Hanusa over the previous production of Europeras 1 & 2 at the Hannover State Opera. [It opened in October 2001, and I confess, I was not paying much attention to German opera gossip at the time.] According to Hanusa, Lowery kept the aria singers offstage, and instead of the chance-derived staging, he created various storytelling set pieces. It sounds almost as bad as Cage’s sabotaged NY Phil debut in 1964.

But it’s better than nothing? I don’t know. Is it the kind of thing you can watch on DVD? Will Europeras ever be staged in the US? [YES, SEE BELOW.] Frankly, we may still not be ready for it. Or maybe we’ve superseded it; with the right code and a few browser tabs on YouTube, we can generate our own Europera anytime we want. Man Bartlett’s #12hPoint, I’m looking at you.

UPDATE/CORRECTION: Thanks to DJW for correcting me; Europeras 1 & 2 was staged in the US. Christopher Hunt brought the original Frankfurt production to Summerfare at SUNY Purchase in 1988. According to John Rockwell’s bemused NY Times’ review, the New York version, which took place on a grander stage, was actually closer to Cage’s original vision, which the Frankfurt Opera had to rework after its main theater was damaged by arson just before the Europeras‘ premiere. Anyway, more to come on that.

* OK, the 639-year-long organ performance of As Slow As Possible, also from 1987, at St. Burchardi church in Halberstadt is also pretty grand. But I’d argue its grandeur is more the performance, not necessarily the composition.

The VW Years, Appendix: Living Theatre

Welcome to another episode of The VW Years, greg.org’s ongoing mission to seek out firsthand accounts of John Cage and Merce Cunningham’s VW Bus.

These are some mentions of John Cage in The Living Theatre: Art, Exile, and Outrage,, John Tytell’s 1995 history/biography of Living Theatre founders Judith Malina and Julian Beck, which were compiled by Josh Ronsen and posted to silence-digest, a Cage-related mailing list in 1998:

“At the end of September, they visited Cage and Cunningham who had expressed an interest in sharing a place that could be used for concerts and dance recitals. Gracious, unassuming, the two men lived in a large white room, bare except for matting, a marble slab on the floor for a table, and long strips of foam rubber on the walls for seating. The environment reflected their minimalist aesthetic. Cage proposed to stage a piece by Satie that consisted of 840 repetitions of a one-minute composition. He advised them not to rely on newspaper advertising, but to use instead men with placards on tall stilts and others with drums.” –pg 72

…

“the only person Judith admitted caring about was John Cage, “mad and unquenchable” with his “hearty, heartless grin.” With Julian, she visited Cage in Stoney Point in the Hudson Valley. … Julian thought Cage was the “chain breaker among the shackled who love the sound of their chains.” Cage collected wild mushrooms, which Julian interpreted as a tribute to his reliance on chance as much as to his exquisite taste. … [Paul] Williams wanted to help them find a new location that Cage and Cunningham could share with The Living Theatre.” -pg 121

“In the middle of 1957, they saw Cunningham dance at the Brooklyn Academy of Music to Cage’s music. At a party afterward, C&C laughed all night like “two mischievous kids who had succeeded in some tremendous boyish escapade.”” -pg 125

“[they] visited Cage in Stoney Point, where they made strawberry jam and gathered mint, wild watercress, and asparagus for dinner. Feeling a surge of confidence in his own writing, he [Julian] gave Cage a group of poems to set to music.” -pg 128

“With Judith, Julian, Cunningham, and Paul Williams, John Cage drove from “columned loft to aerie garage” in his Volkswagen bus, smiling despite the traffic and the fact that their search was now in its 4th month. Finally, they found an abandoned building, formally a department store on 14th st and 6th ave, which Williams declare would be suitable for sharing as a theatre and dance space.” – pg 129

“Early in December, with Cage’s assistance, [Cunningham] moved some of his backdrops into the space. Cage brought with him a variety of percussion instruments–he owned more than 300 at that time–which he donated to the theatre. Julian thought there was a distance about Cage that prevented intimacy and the fullest communication, but he felt Cage’s gift was a real sign of the artistic support that would be crucial to the success of The Living Theatre.” -pg 140

The VW Appears

image: copyright the John Cage Trust, used with permission

So awesome. Last winter, I tried to dig up all the published firsthand accounts and references of The VW Years, Carolyn Brown’s term for the early days of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, when the troupe would tour the country in John Cage & Merce’s white VW bus, which Cage had purchased using the winnings from a rigged Italian game show.

In addition, I’ve tried to figure out what happened to the bus itself. So far, no luck at all. But when she was helping with the transfer of the Cunningham Foundation archives to the NY Public Library, John Cage Trust director Laura Kuhn spotted this little image of the company hanging out next to the bus. And she very graciously sent it along. Many thanks.

The VW Years, Ch. 1

Ch. 2, Remy Charlip & Steve Paxton

Ch. 3, John Cage

The VW Years: Carolyn Brown, Part I, Part II

Things We Were Going To Do Are Now Being Done By Others.

And speaking of big universes and small worlds, I’m starting to listen to the 1991 recordings of John Cage’s Diary: How To Improve The World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse), and just ten minutes in, I’m reminded that Cage’s childhood friendship with the unorthodox-but-nearly-canonical Mormon scholar Hugh Nibley is the most unlikely Mormon/modern music connection since La Monte Young [grandson of Brigham].

Without intending to, I’m going from lake to lake

Salt air

Salt Lake

Hugh Nibley

I hadn’t seen him since high school days

I asked him what he thought about other planets

and sentient populations.

“Yes,” he said, “throughout the universe.

It’s Mormon doctrine.”

We’d said goodbye.

I opened the door of the car,

picked up my attache case,

and everything in it fell out on the grass

and the gutter.

His comment:

“Something memorable always happens.”

Which, hmm, if it only served to get me into a transcribing-and-posting mind for the next excerpt Cage read, then it’s worth it:

Things we were going to do

are now being done by others.

They were, it seems, not in our minds to do.

Were we or they out of our minds?

But simply ready to enter any open mind

any mind disturbed enough not to have an idea in it.

Has Erik Satie Been Performed On US Network Television Since 1963?

This 1963 episode of I’ve Got A Secret pops up periodically. From this week on Boing Boing to Alex Ross’s 2007 blog post searching for Karl Schenzer.

And it is, indeed, pretty interesting. John Cale was recently arrived in New York City–Ross notes that he got a ride down from Tanglewood in Iannis Xenakis’s car–and still a couple of years away and a stint under LaMonte Young’s sway from forming the Velvet Underground. John Cage enlisted him and some other sympathetic pianists to perform Vexations, an epic 1949 composition by Erik Satie, for the first time. That was Cale’s secret. Schenzer’s was that he alone stayed for the entire 18-hour performance.

Of course, Cage himself had appeared on I’ve Got A Secret in 1960, giving a raucous rendition of his composition, Water Walk, while dressed, typically, like a Methodist minister.

Three years later, Cale and Schenzer also exude a buttoned-up, Cageian seriousness, but what caught my attention was Schenzer’s namecheck of the concert’s sponsor, the Foundation for Contemporary Performance Arts, which Cage and Jasper Johns had just launched.

By 1963, I guess these folks were becoming better known, and certain of them, particularly Johns and Rauschenberg, were selling a fair amount of artwork. Yet as soon as they had two nickels to rub together, these artists were using the money to support and propagate the work of their fellow artists.

And it really amazes me to think that the cultural factions of the time were still so close together that this avant garde crew could turn up on a network TV game show. John Cage may have turned up at some point in the intervening 30 years, but it’s very easy for me to imagine that the first mention of Erik Satie on CBS was also his last.

The VW Years: Carolyn Brown, Part II

After processing the odd hippie hipness of the idea of John Cage driving Merce Cunningham and his dance company around the country in a VW Microbus, it was really dancer Carolyn Brown’s excellent memoir that persuaded me to see the bus as central to this incredible, historic period. So I’m going to quote from an extended section of Chance and Circumstance: Twenty Years With Cage And Cunningham, and then expect everyone to go read it themselves. Because it’s an awesome tale of an exciting career. Brown really shows both self-reflection and an awareness of those around her. And those around her included some of the greatest artists of the last hundred years.

Anyway:

The VW Years: Carolyn Brown, Part I

Well first off, apologies to Remy Charlip. I’d said he was “a bit off on dates” when he wrote about touring with Merce in a VW Microbus driven by John Cage from 1956-61. When we know [sic] that Cage only bought the bus in 1959, after winning a stack of dough on a rigged Italian game show.

Well first off, apologies to Remy Charlip. I’d said he was “a bit off on dates” when he wrote about touring with Merce in a VW Microbus driven by John Cage from 1956-61. When we know [sic] that Cage only bought the bus in 1959, after winning a stack of dough on a rigged Italian game show.

But now, who knows? Those dates match up perfectly with the memoir of Carolyn Brown, one of Merce’s first principal/partners, and, like Charlip, a member of the Company from the earliest Black Mountain College days.

In fact, the chapter of Chance and Circumstance which lent its title to this series of posts, “The VW Years,” begins in:

November 1956. John and Merce borrowed money to buy a Volkswagen Microbus, the vehicle that defined–willy-nilly–a classic era of the dance company’s history: the VW years. Our first VW-bus jaunt was crazily impractical, but according to a postcard sent to my parents, “a very happy trip.” To give two performances, we drove for two days and one-third of the way across the country and, although I don’t know how Merce was able to afford it, we stayed, for all the world like a professional dance company, in a big city hotel–the Roosevelt in downtown St. Louis. [p. 164]

What’s remarkable about these “VW Years” in the mid-50s was how little use the bus actually got. The centerpiece of the chapter is actually a groundbreaking Jan. 1957 performance at BAM that caused a downtown uproar–but which was followed by months-long stretches of absolutely nothing at all. The company performed so little in 1957 that Brown ended up joining the ballet corps at Radio City Music Hall, a grueling gig that left her exhausted and injured, but with money in the bank.

The detailed, finely, painfully felt atmosphere Brown conjures up is both eye-opening and engrossing; the rejection, ignoring crowds, poverty and hardship of this era of Merce & co’s career–indeed, of the whole downtown scene–seems hard to imagine from the comfortable, iconic present. And though I’m neither a big biography nor dance guy, I repeatedly found myself thrilled and literally laughing out loud at Brown’s stories.

The VW Years were also the Bob and Jap years, when Rauschenberg and Johns designed costumes and sets for the Company. In 1958, the two artists and Emile de Antonio produced a 20-year concert retrospective of John Cage’s work, followed in Feb. 1960 by a Manhattan performance for Merce’s company.

Merce worked out the program for what would turn out to be a “traumatic” New York performance on a tour through Illinois and Missouri:

After the eleven-day tour, six of them spent in the close quarters of our Volkswagen bus, everyone had or was getting a cold. In Viola [Farber]’s case the cold developed into bronchial pneumonia. By February 16 she was acutely ill. At the end of her umbrella solo in Antic Meet her legs were cramping so badly she barely made it into the wings. Merce, entering from the opposite side for his soft-shoe number, couldn’t help seeing her, on the floor in the wings, unable to walk, tears streaming down her face. Afterward he said that as he went through the motions of his solo his mind was racing: What happened? Will she be able to continue? What will we do if she can’t? At the intermission he picked her up in his arms and carried her upstairs to the women’s dressing room. The cramps finally subsided and she assured him she could continue. Cod knows how she got through Rune, but she did. [p. 260]

Brown is sympathetic but unflinching in her account of the difficulties of working with Cunningham, and of the toll the company’s lack of performances and new choreography took on Merce the dancer, who, in Brown’s telling, grew grim and depressed as he watched his peak physical years passing him by. By 1961, things were not quite so grim, with ten performances booked in nine states between February and April; which may make this the Golden VW Year:

I think Merce was even more relived than I to be touring with the full company, and his self-confidence seemed fully restored knowing that the company had been engaged on the basis of his reputation as dancer and choreographer rather than by avant-garde musical festivals based on John’s and David [Tudor]’s reputations. John and David were with us, of course, to play piano for Suite and Antic Meet. John, on leave from Wesleyan, also resumed his duties as chief chauffeur, cheerleader, guru, and gamesman. Once again, nine people tucked themselves into the Volkswagen Microbus, sometimes spending as many as eighteen out of twenty-four hours together. Singing, snoozing, reading, knitting, arguing, laughing, telling stories, playing games, munching, and sipping, we whiled away the hours and miles between New York City and De Kalb, Illinois, De Kalb and Lynchburg, Virginia…etc. We totaled six days and one full night on the road plus six hours in the air just to give four performances. Ridiculously long journeys. One performance we gave having had no sleep at all, dancing in Lynchburg, Virginia, on Tuesday night, then, after a party, driving all night to Richmond, Virginia, to catch a plane to Atlanta and another to Macon, where we performed Wednesday night after rehearsing in the afternoon. It was impractical. Exhausting. Wonderful. [pp. 313-4]

There’s one more excerpt which I’ll go ahead and quote from at length, where Brown really brings home the reason why I’ve become kind of fascinated with Cage’s VW bus in the first place. At 11PM, as the year ends, and Merce Cunningham Dance Company is performing for the last time at the Park Avenue Armory–and as I gave my tickets to these final Legacy Tour events to a good friend when I realized our travel schedule meant we couldn’t attend ourselves–and as Cage’s centennial year begins, I am looking forward to soaking in Brown’s insightful account of the scrappy, crazy, foundational era of the company and the artists in its orbit.

“The Final Bows: Merce Cunningham Dance Company, December 31, 2011” [@parkavearmory]

The VW Years, Ch. 3: John Cage

The VW bus makes many appearances in John Cage’s own writings, especially his tour diaries in Empty Words: Writings ’73-78:

After winning the mushroom quiz in Italy, I bought a Volkswagen microbus for the company. Joe’s was open but said it wasn’t. At Sofu Teshigahara’s house, room where we ate had two parts: one Japanese; the other Western. Also, two different dinners; we ate them both.

We descended like a plague of locusts on the Brownsville Eat-All-You-Want restaurant ($1.50). Just for dessert Steve Paxton had five pieces of pie. Merce asked the cashier: How do you manage to keep this place going? “Most people,” she replied rather sadly, “don’t eat as much as you people.” [p. 80]

…

Tarpaulin centered on the bus’s luggage rack, luggage fitted on it. Ends’n’sides were folded over; long ropes used to wrap the cargo up. [p. 82]

…

We were waiting to be ferried across the Mississippi. We had nothing to eat. We waited two hours. It was cold and muddy. When we decided to leave, Rick and Remy had to push the bus up the hill. Later we learned that the ferry service had been discontinued two years before. [p. 90]

…

Pontpoint: the company ate by candlelight. Everywhere we’ve gone, we’ve gone en masse. A borrowed private care took two, two such cars took six to eight, the Volkswagen bus took nine. Now airplanes and chartered buses take any number of us. Soon (gas rationing) we’ll travel like Thoreau by staying where we are, each in his own. [p. 95]

In Richard Kostelanetz’s John Cage: an anthology, the dance critic Stephen Smoliar recounted one story Cage told the audience at opening night of the company’s 1970 season at BAM:

The Cunningham Company used to make transcontinental tours in a Volkswagen Microbus. Once, when we drove up to a gas station in Ohio and the dancers, as usual, all piled out to go to the toilets and exercise around the pumps, the station attendant asked me whether we were a group of comedians. I said, “No. We’re from New York.”

This pushes back the end of The VW Years to the 60s at some point.

The VW Years: Ch. 2, Remy Charlip & Steve Paxton

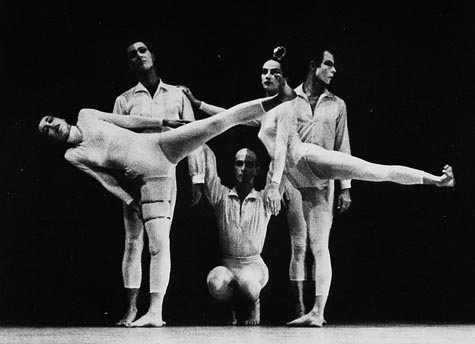

[l to r] Viola Farber, Bruce King, Remy Charlip, Carolyn Brown & Merce Cunningham performing Nocturnes in 1956. photo CDF/Louis A. Stevenson, Jr. via the estate project

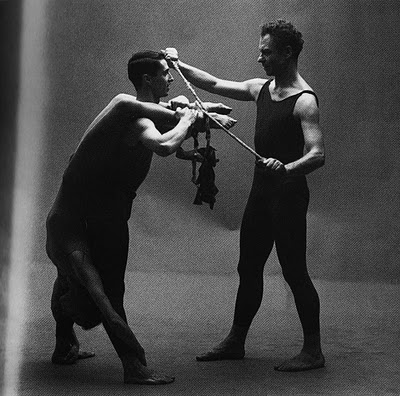

Remy Charlip was an early collaborator in Merce Cunningham’s orbit. Years before he began his second or third acclaimed career as a children’s book illustrator and author, Charlip danced with Cunningham and Martha Graham in New York and at Black Mountain College. He created the programs for the August 1952 Cage et al performance at BMC which is considered the first “Happening.” They were printed on cigarette paper, and were placed at the entrance next to a bowl of tobacco, with an ashtray on each seat.

image of what has to be a Charlip program for a different Cage performance, via The Arts at Black Mountain College

Though he’s a bit off on the dates, what with Cage only buying the VW bus in 1959, John Held’s Charlip biography lays out the basic configuration of the bus:

As if BMC was not enough, Charlip received continuing post-graduate work from 1956-1961 in the back of a Volkswagen Microbus driven by John Cage, navigated by Merce Cunningham, enlivened by Robert Rauschenberg, with traveling companions Nicholas Cernovich and dancers Carolyn Brown, Viola Farber, Steve Paxton and others.

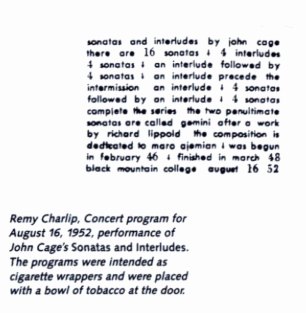

[l to r] Carolyn Brown, Steve Paxton & Merce Cunningham, 1961, image via cepress

A couple of weeks ago, Paxton talked to the Washington Post about the bus: Later that year [1960? ’61? -ed.] Remy resigned, and I was invited into the smaller company. This meant touring around the U.S. in a Volkswagen bus, which, I was informed, it was my duty to pack. And unpack. And distribute and later collect all the items packed. There were the spaces under the seats, a compartment in the back, and a roof rack to transport nine persons’ personal luggage, the equipment of John Cage and David Tudor for various musical adventures, and the sets and costumes for the tour. The bus was heavy laden, and it never let us down, including at least two tours the the West Coast.

John or Merce drove, and John liked to play Scrabble when off-duty. The rest of us conversed and Viola [Farber] knitted. It was rather like a family around the hearth. Long silence, naps, breaks to stretch and walk about, and usually some amazing treat produced by John, a huge salad perhaps, or once Rogue River pears at perfect ripeness with pear liquor to accompany. David was quiet, Marilyn Wood chatty, Carolyn [Brown] and Viola made comment, Merce sometimes spoke, John and Bob laughed a lot, and both were great story-tellers. I remember the actual driving fondly.

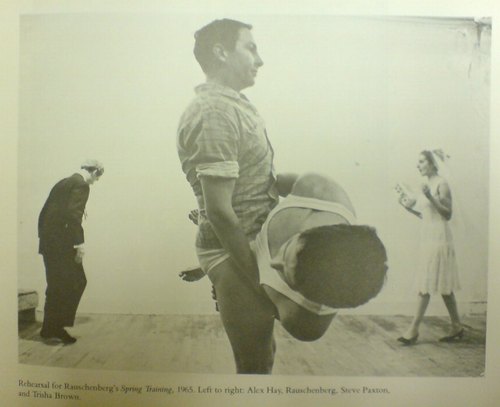

It may have been amidst family-like intimacy of the bus that Paxton and Rauschenberg started the relationship that ended the relationship between Rauschenberg and Johns in 1961-2.

Robert Rauschenberg & Steve Paxton, with Alex Hay [l] and Trisha Brown [r] rehearsing Spring Training, 1965. image via SAAM Rauschenberg catalogue, 1976