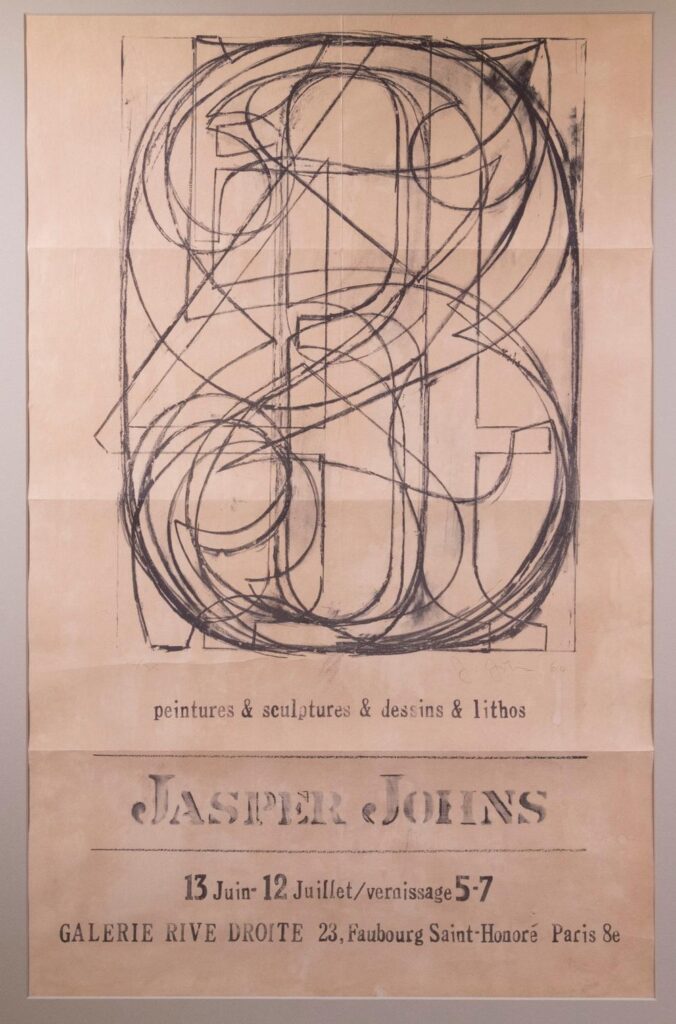

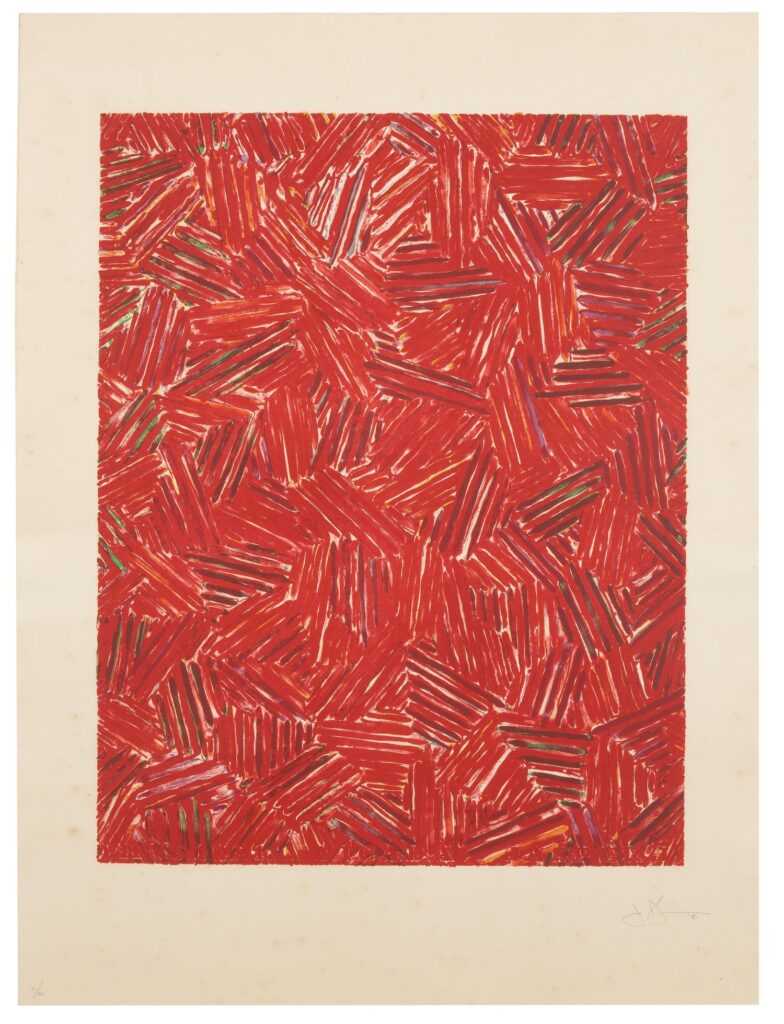

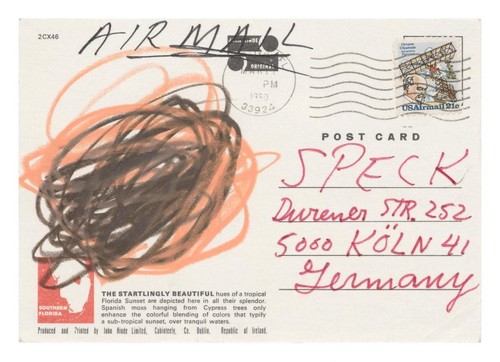

Even MoMA lists it as 1960, and they got their copy from the artist in 1961, so maybe. But the exhibition being announced here, Jasper Johns’s first show in Europe, absolutely took place in the Summer of 1961.

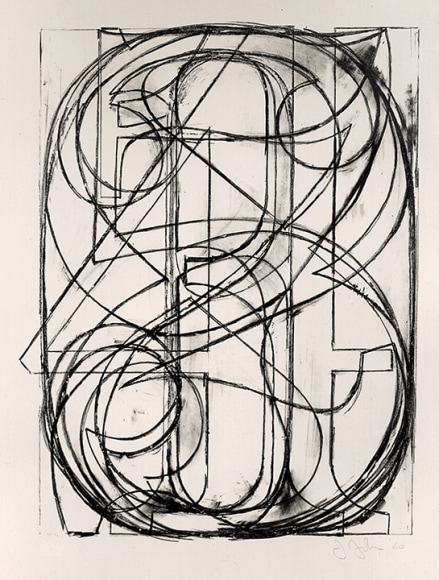

I get the confusion, though. Because the poster—most were actually mailers—reproduces a Johns lithograph, signature, date, edition number and all. 0-9 (ULAE 3), 1960, was published in an edition of 35. And whoever got No. 28 photographed it for this poster. Did the Galerie Rive Droite produce the poster, with Johns’s name in his already distinctive stencil? Or was it made in the US? That freeform accent over the Saint-Honoré makes me wonder. In any case, it has a nearly uniform handmade elegance that belies its offset print reality.

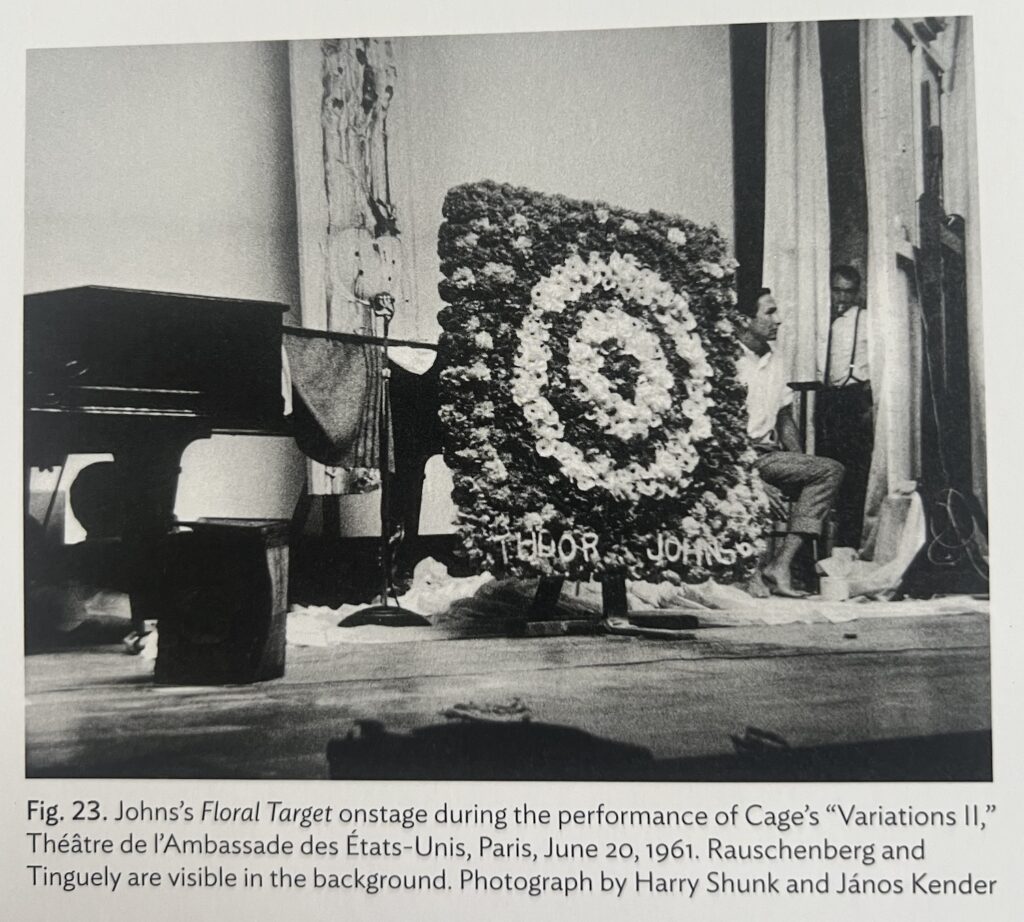

Galerie Rive Droite was around the corner from the US Embassy where, in the week after his opening, Johns, Rauschenberg, Jean Tinguely, and Niki de St-Phalle organized an art-filled performance for pianist David Tudor. June 20, 1961.

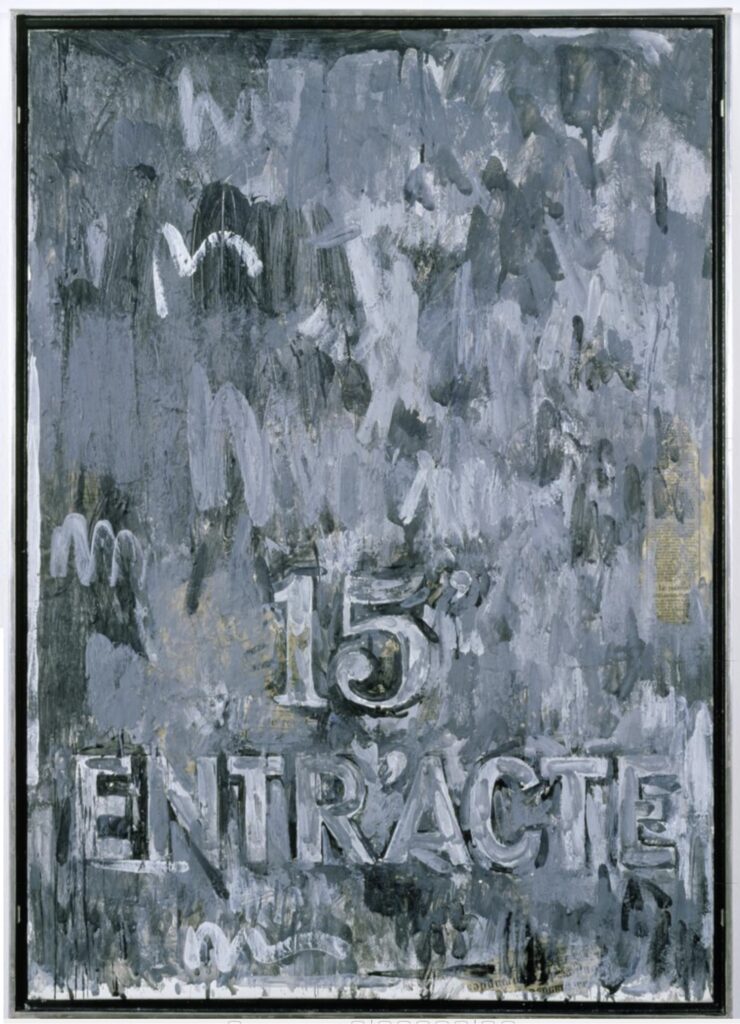

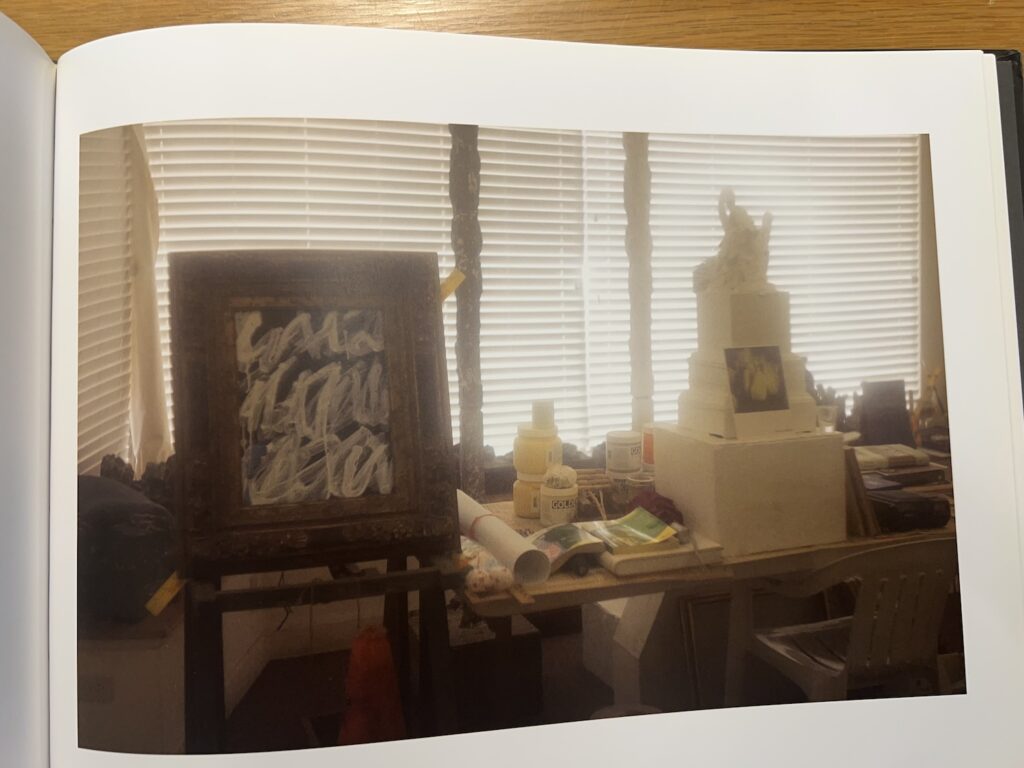

Johns sent flowers in the shape of a target* and whipped up a painting in the Paris studio of Alabamian ceramist Fance Franck. Though there was no actual intermission and the action never stopped, Entr’Acte was placed on stage for 15 minutes. Like the Sculp-metal 0-9 collage in the exhibition, Entr’Acte was bought by the secretary at Galerie Rive Droite, Georges Marci.

But was it really? To Google her now, Georges Marci shows up in the provenance of various blue chip artworks, is repeatedly called the “grand dame of contemporary art in Switzerland,” which has to be a self-anointed thing, and is known for opening the first gallery in Gstaad. But I guess people never thought the tapes would be made public, because in her 1974 oral history for the Archives of American Art, dealer Judith Richardson basically called Marci a thief who murdered her husband.

Richardson worked for both Sidney Janis and Ileana Sonnabend, Castelli’s ex. Which meant she worked with many overlapping artists with Galerie Rive Droite, run by Jean Lecarde. Lecarde wanted to open a gallery in Switzerland, and to get around the residency requirements, he transferred all the inventory to Marci’s name. And then she just froze him out and kept it, and he went bankrupt. This is how Arman tells the story, Richardson said. Arman was there, she said he said, when Marci set her depressed Egyptian husband up with the pills he used to kill himself. And then she got all his Coptic art.

Anyway, where were we? Johns found encaustic in Paris, borrowed a studio, and made this painting in like a day or two. While also finding time with Bob to shoot some paintings at St Phalle’s. Eric Doeringer just saw one at the Tate, shot by both Rauschenberg and Johns, and texted me about it. Turns out it was in St Phalle’s show that opened June 30, 1961. A busy summer in Paris.

Previously, related: The Performance Art in Embassies Program

* I have long wanted to see, then make, this flower arrangement, but I can’t remember where I’ve ever seen a photo of it. Somewhere, though. I’ll look.

In her MoMA retrospective, Leah Dickerman had a photo of Rauschenberg painting on stage while David Tudor played the piano. But she also said Johns carried his painting on stage to signal intermission, while Tomkins said Johns refused to go on stage. Both could somehow be true.

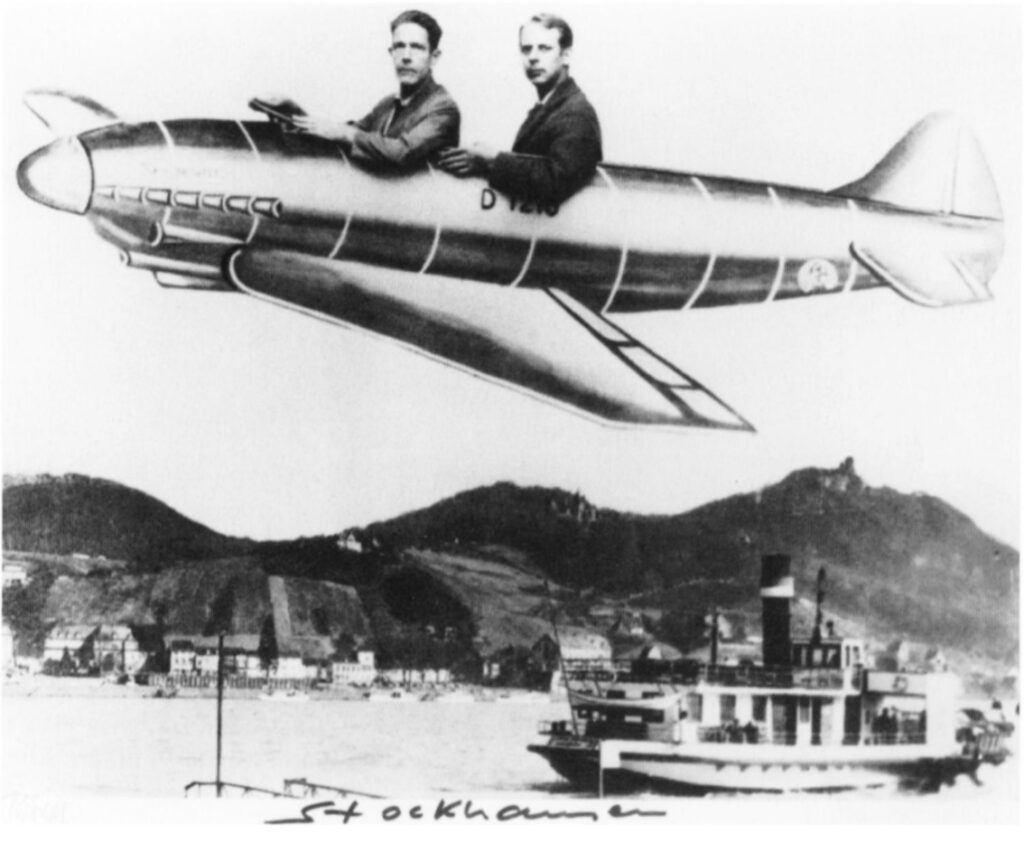

I knew I’d seen it somewhere. A closer look at Roberta Bernstein’s chronology shows Johns was booked and very busy in Paris: he made two plaster casts** in Tinguely’s studio; his costumes appeared on Merce dancers June 12; his show opened June 13; Tudor’s performance on the 20th; and he helped install Saint-Phalle’s show, which opened on the 28th. Also, what part of this itinerary did Shunk & Kender plan to be there for? Because it is amazing that they were around for an impromptu concert that came together in a matter of weeks.

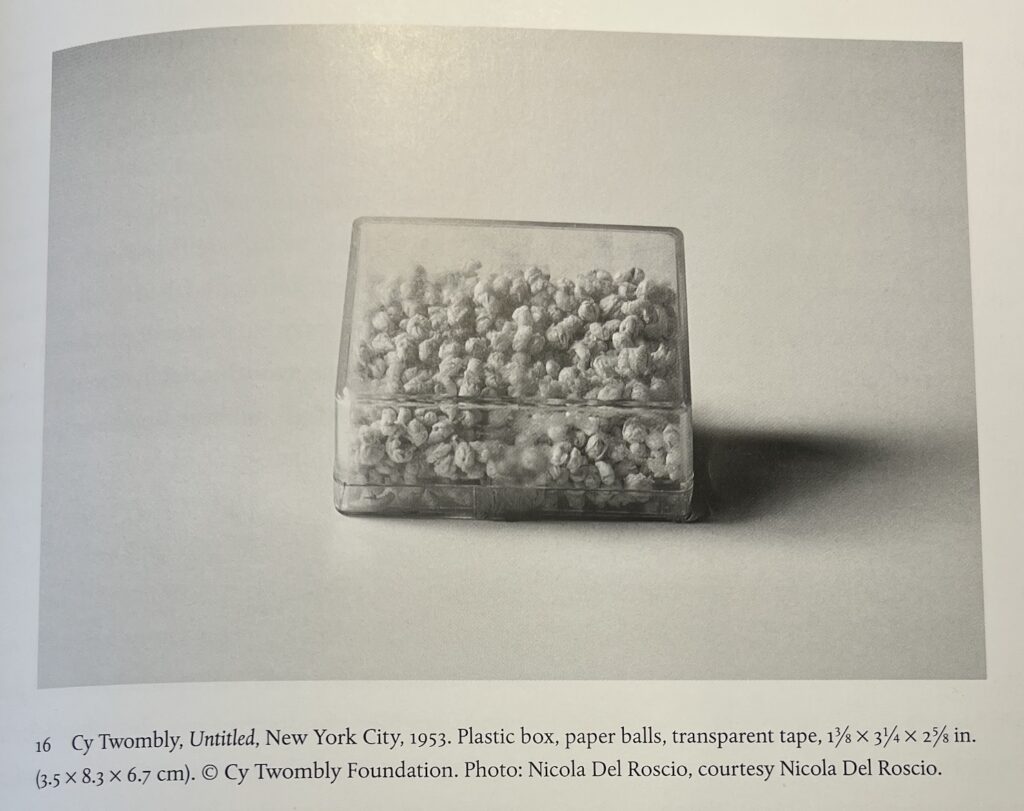

** About those plaster casts: they were made from moulages made of the sculp-metal 0-9 and a similar Figure 3 from the Rive Droite show. So a 2nd generation cast. Which Johns used to promptly cast four more 0-9 in aluminum and, in 1997, four Fig. 3 in bronze. I low-key love that this feels like Johns wanting to keep engaged with works of his own that he expects not to see again, at least for a while.

![a google streetview screenshot of the back of a durer painting in the state museum in karlsruhe, germany, which is mounted on a white pedestal in a black and gold edged frame. the back of the painted panel is swirling red green pink blue, pale yellow, interpreted as a slice of agate, and I forget what's on the front. some devotional image of jesus [love him, don't get me wrong, but not the point rn] the gallery floor dominates the image; it is strip wood. the walls are pale grey with a dark grey stone baseboard. google streetview cruft and ui elements abound obv](https://greg.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/durer-ecce-homo-verso-google-streetview-1024x717.jpg)

![a robert rauschenberg screenprint of a collage made of clippings from newspapers in 1969, includes [clockwise from top left] a photo of cars stranded in the snow; a white woman in a miniskirt with a longer skirt drawn over her; a comet; ted kennedy, some racist judge nixon tried to put on the supreme court who eventually got voted down because twelve republicans still had enough conscience left to be shamed over unalloyed white supremacy, can you even imagine? anyway, several articles and photos of gm assembly lines and the threat of robots and depleted pensions; a chevron tanker truck overturned on a freeway; a hand holding a case of birth control pills; a sideshow entrance with the world's largest rats; a coal mining ship and a truck being craned onto a ship; more assembly line; and a ship docking on the hudson pier. from the 26-print portfolio known as Features from Currents, being sold at Wright 20 in apr 2025](https://greg.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/rauschenberg_currents_portfolio-wright20-202504-283-1001x1024.jpg)