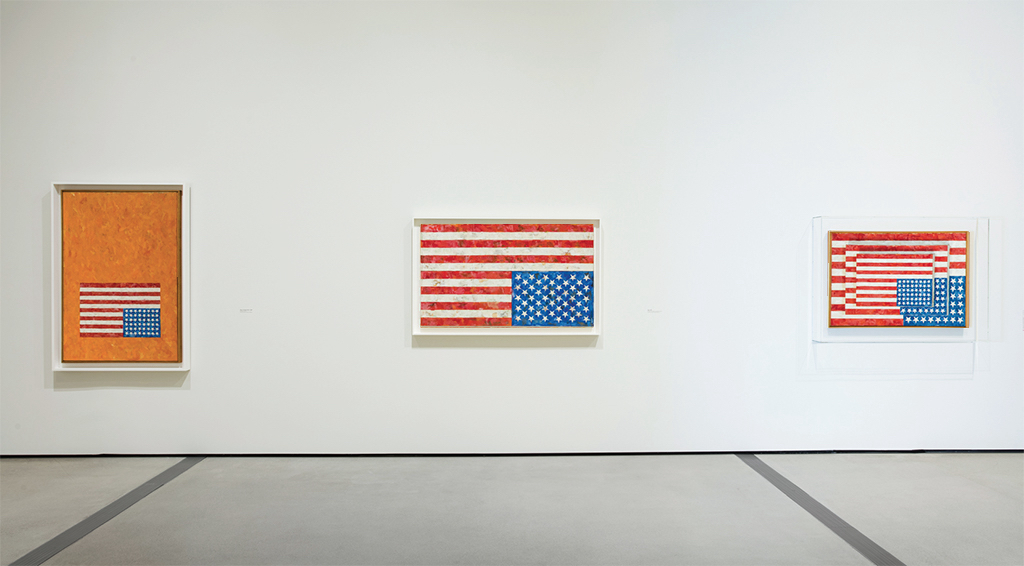

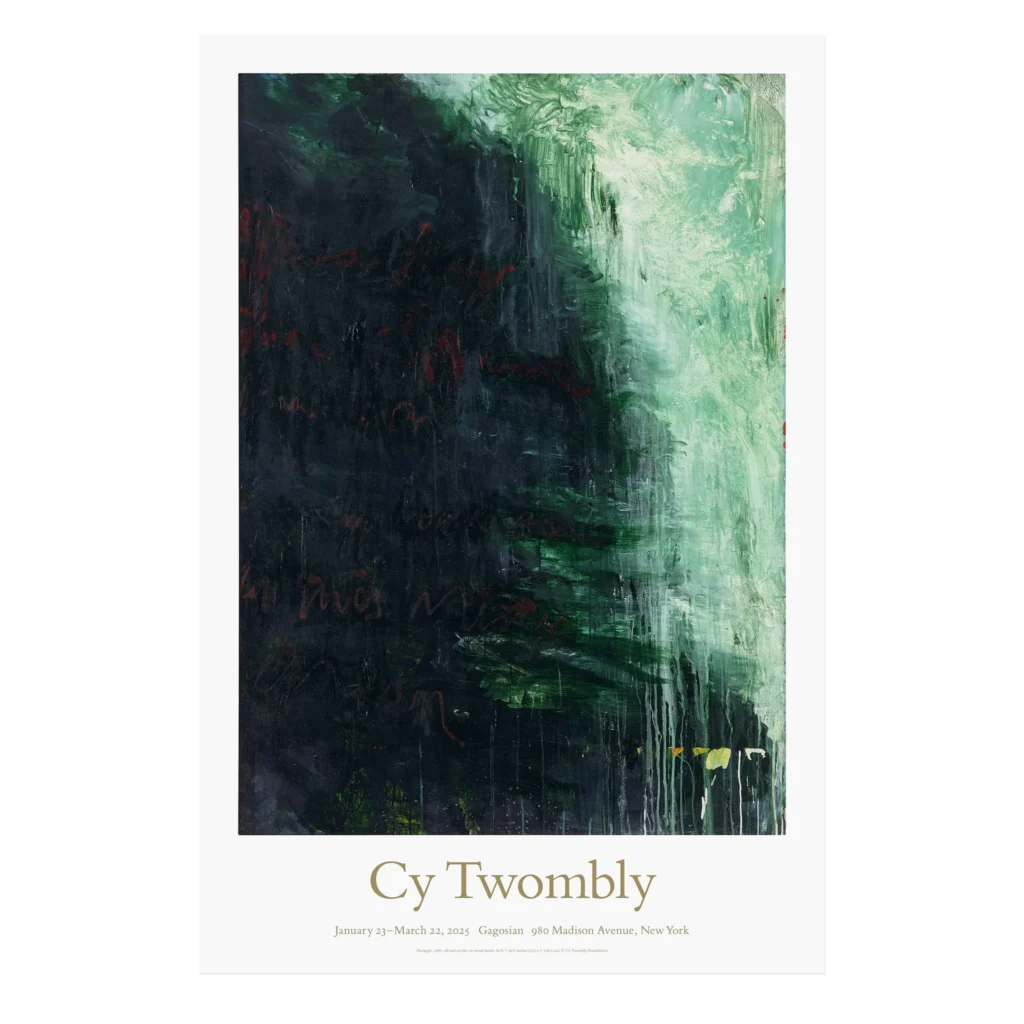

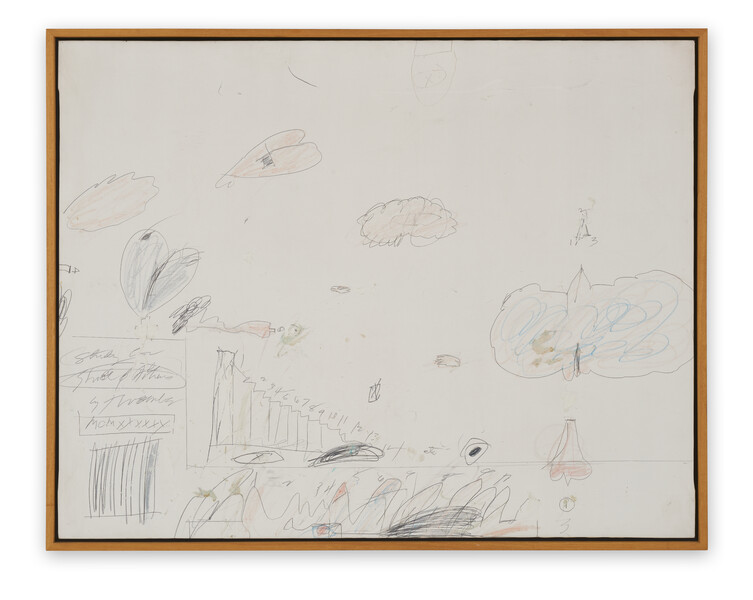

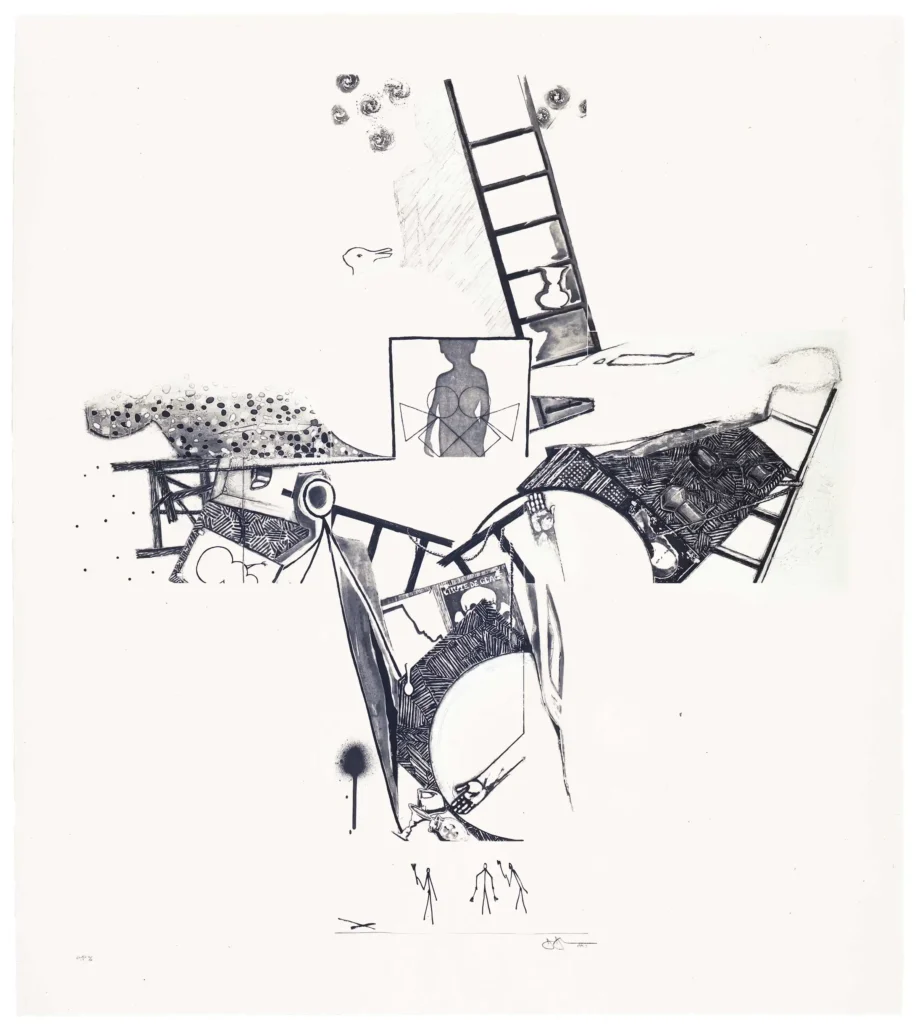

![a robert rauschenberg screenprint of a collage made of clippings from newspapers in 1969, includes [clockwise from top left] a photo of cars stranded in the snow; a white woman in a miniskirt with a longer skirt drawn over her; a comet; ted kennedy, some racist judge nixon tried to put on the supreme court who eventually got voted down because twelve republicans still had enough conscience left to be shamed over unalloyed white supremacy, can you even imagine? anyway, several articles and photos of gm assembly lines and the threat of robots and depleted pensions; a chevron tanker truck overturned on a freeway; a hand holding a case of birth control pills; a sideshow entrance with the world's largest rats; a coal mining ship and a truck being craned onto a ship; more assembly line; and a ship docking on the hudson pier. from the 26-print portfolio known as Features from Currents, being sold at Wright 20 in apr 2025](https://greg.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/rauschenberg_currents_portfolio-wright20-202504-283-1001x1024.jpg)

Though Our Most Important Art Historians disparage the practice, I could not resist zooming in to read the specific newspaper clippings that Robert Rauschenberg included in just one his 26 Currents prints. Honestly, I did not expect them to hit so hard, one after the other:

The threat of robots taking union jobs

The threat of executives taking union pensions

Gas tanker overturned on a freeway causing mayhem

WORLD’S LARGEST RATS

Birth control

Woman’s outfit-shaming

A problematic Kennedy

A criminal president’s supreme court nominee being exposed as a mediocre southerner whose only firm conviction is white supremacy, getting defended by an unperturbedly anti-semitic republican senator saying, “Even if he were mediocre, there are a lot of mediocre judges and people and lawyers. They are entitled to a little representation, aren’t they, and a little chance? We can’t have all Brandeises, Frankfurters and Cardozos.”

Even the auction itself, a couple of loosies being stripped and sold off piecemeal, feels topical: people don’t buy 26-print portfolios these days anymore than they read newspapers. And yet the politics and the challenges remain the same.

3 Apr 2025, Lot 283: Robert Rauschenberg, from the [Features from] Currents Portfolio, est. $1,000-1,500 [wright20]

Related: Features from Currents, 1970; Surfaces from Currents, 1970 [moma]