I have reviewed the chronology of Jasper Johns’ stick figures, and it is long, and the literature, and it is sparse. The most extensive discussion I’ve found of them is from July 2020, when art historian Isabelle Loring Wallace explored figures and faces in Johns’ prints at the Walker Art Center. [The Walker has a complete run of Johns’ print works, which the artist has been topping up with gifts since 1987.]

Loring calls them both “A motif of unknown origin” and “a crudely rendered Picasso-inspired trio,” seeing a similarity to the figure in Picasso’s 1958 UNESCO mural, The Fall of Icarus. I don’t see it, but sure. Except while other Picasso references appear in Johns’ work sooner, this so-called Icarus doesn’t turn up in Johns’ work until 1992, a full decade after the stick figure trio.

[“So-called” because it turns out the Icarus title came from the director of the International Council of Museums, who was on the UNESCO commissioning committee, and who rejected Picasso’s own title? And Picasso never provided a specific narrative reading of the mural, calling it only “a simple scene of bathers.” Maybe a reluctance to be pinned down or pushed toward a single meaning is the real connection between Picasso and Johns worth considering here.]

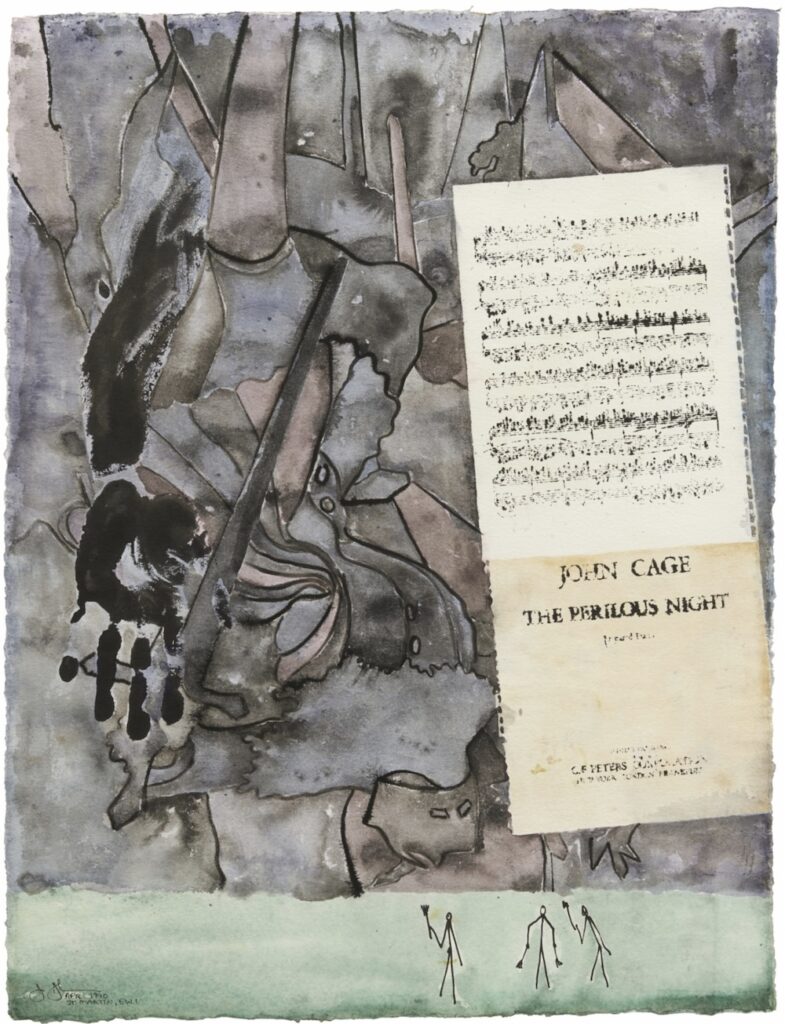

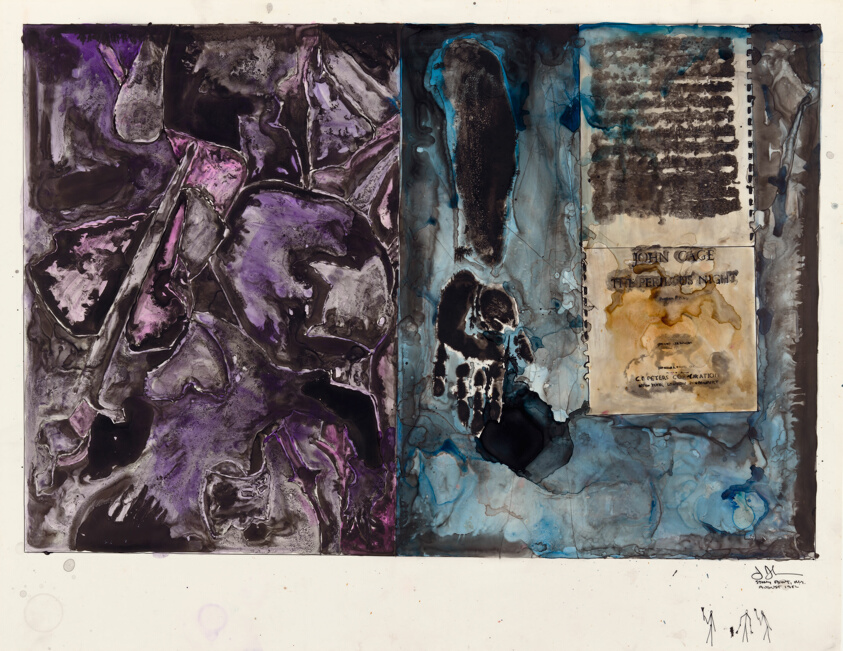

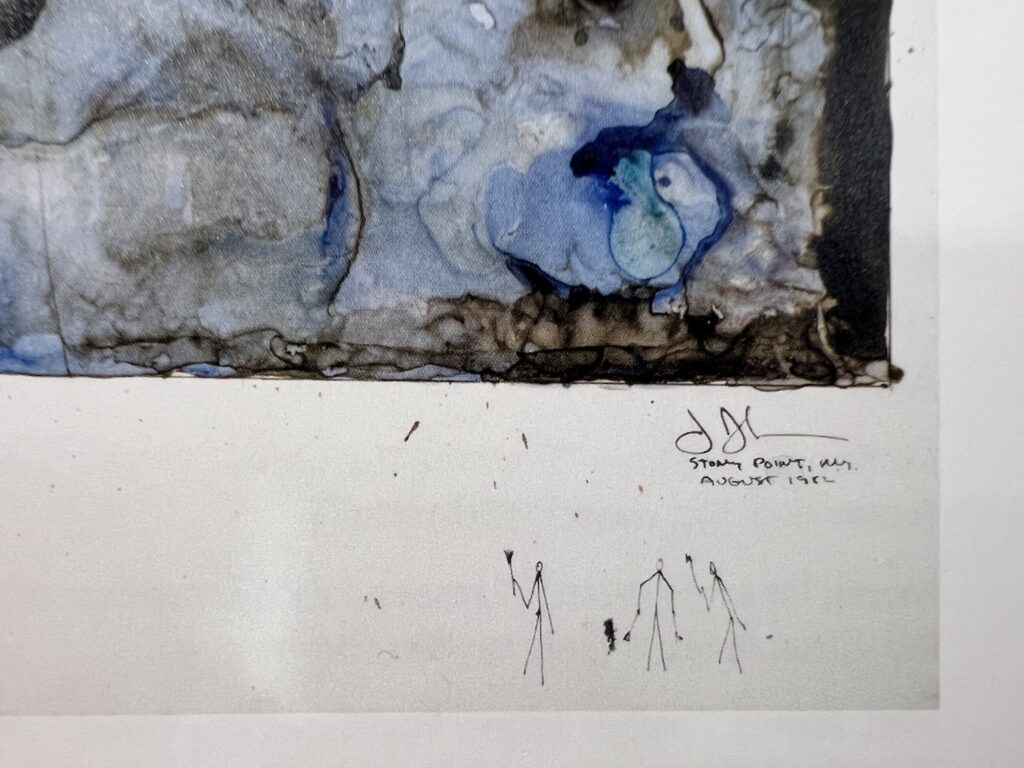

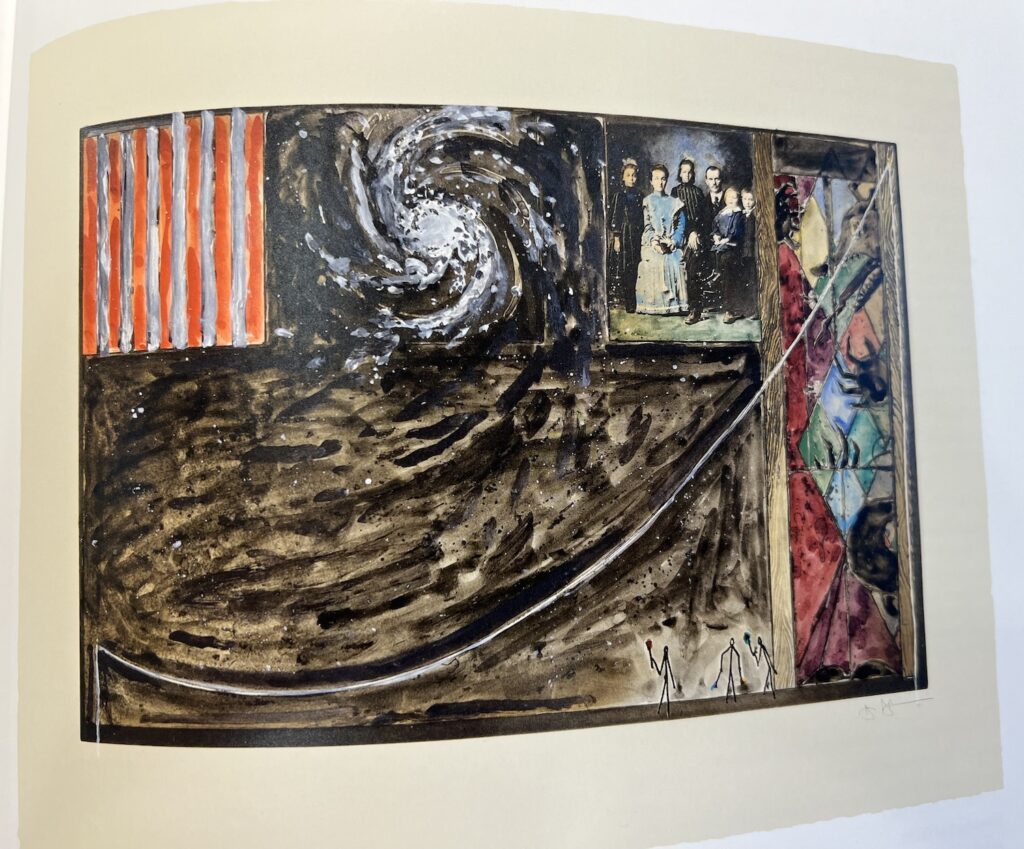

Anyway, the earliest stick figures you can see today (well, tomorrow, since Marks is closed on Mondays) is the watercolor up top, D497 in the CR, which turns out to be one of two Perilous Night works on paper Johns made with little guys in 1990. [The other, D498, was a gift to pianist Margaret Leng Tan, a longtime collaborator and interpreter of John Cage.] The next earliest appearance was all the way back in 1982, in a larger Perilous Night on plastic [D346 above and below]. Just look at those little guys!

The note in the catalogue raisonné says the figures are holding brushes, so not anything else: rakes, spatulas, or a hatchet, which the one on the right does still look like to me tbh. But it also says, “The motif recurs frequently in the 1980s and 1990s.” Which, at least for the ’80s, I think, is not the case at all.

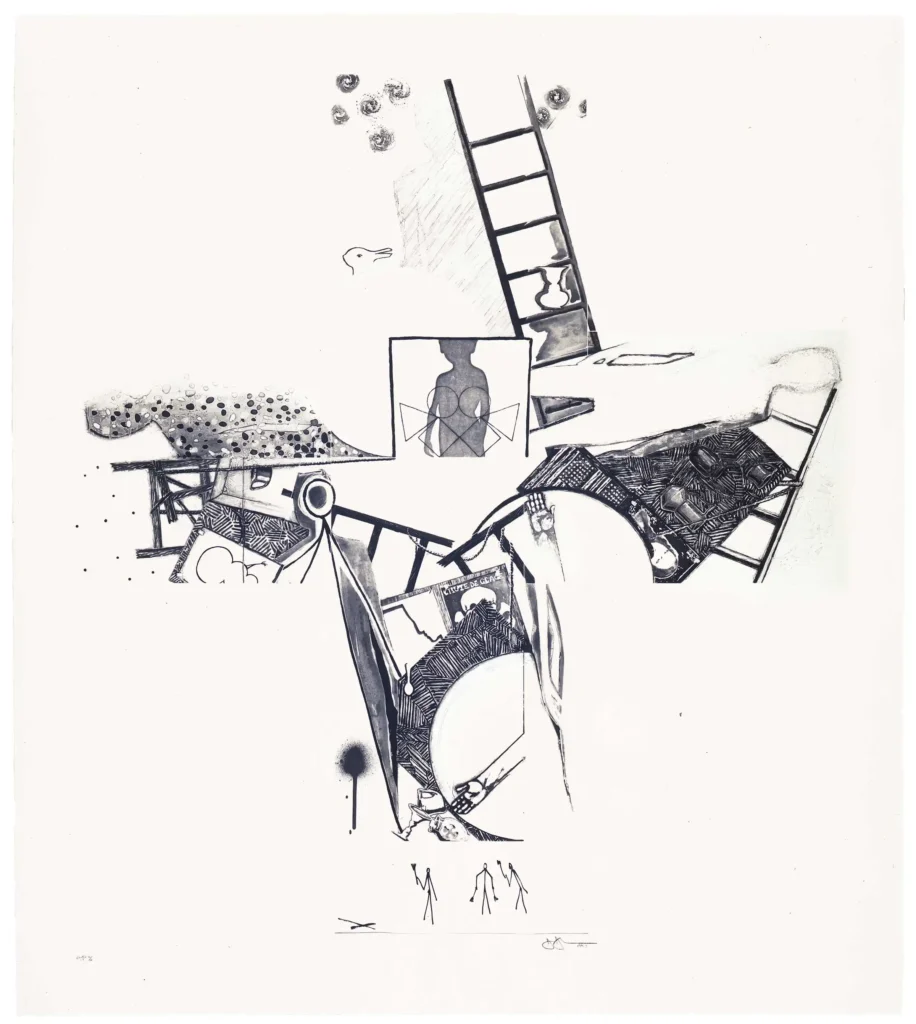

Besides and perhaps before the Cage-related watercolors, Johns put the stick figures in The Seasons (1990), a large intaglio published by ULAE. Like in the 1982 Perilous Night, the figures stand apart, outside the main part of the picture, as if surveying it. The original Perilous Night guys read as being in the margin, except by drawing them there, Johns by definition, eliminates the margin, or incorporates it into his drawing. [Though they remain in roughly the same place in both 1990 Perilous Night watercolors, the little guys are surrounded, or surrounded and framed, by the full-bleed painted/drawn picture; which they were never outside it to begin with.]

For a print, they necessarily have to be inside the margin, on the plate, to get printed, though The Seasons keeps them apart from the central composition. And so it reads like they’re observing the jumbled parts pile of the autobiographical painting and print series that had occupied Johns for most of the last half of the 80s. [December 2024 update: among the hundreds of proof prints Johns has donated to the National Gallery is a test of the two stick figure plates. The lower plate with the Little Guys is around 4 x 6 in.]

[April 2025 update: well, the country’s going to fascist hell in a handbasket, but thanks to Judith Weschler and Hans Namuth’s 1990 film of the artist at work, we have documentation of Johns discussing the first reappearance of the stick figures, in The Seasons intaglio. So at least there’s that.]

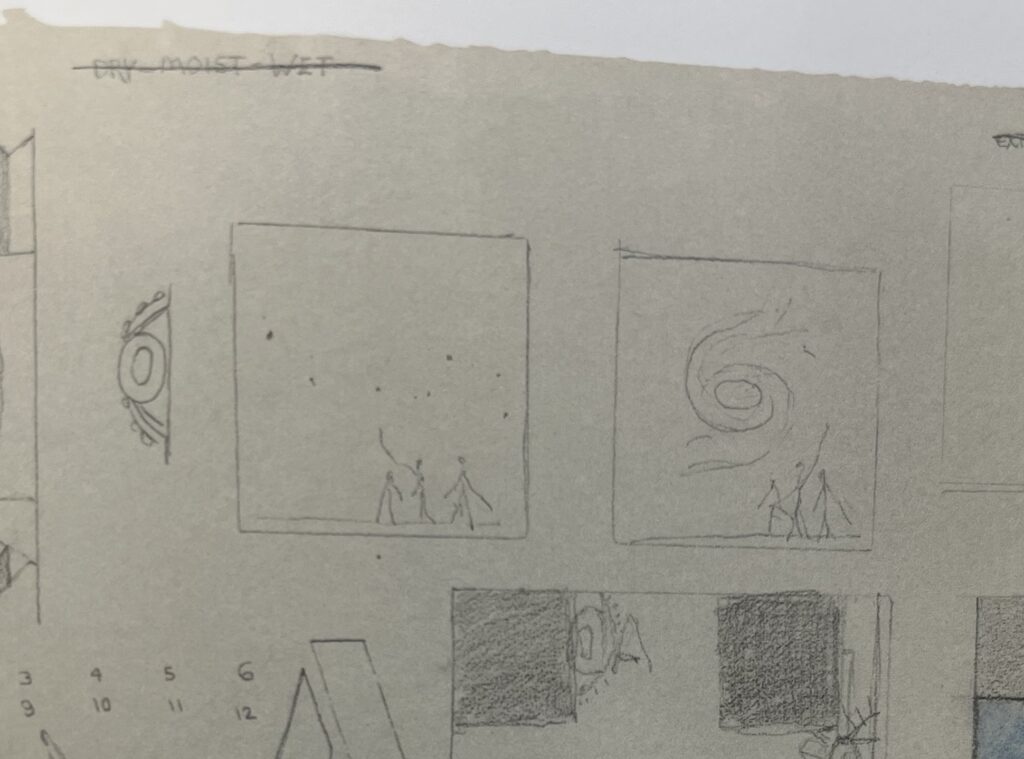

The stick figures pop up a very few more times in the early 1990s. Two panels from a larger sheet of sketches from 1997 show Johns seeing what else they can do to show scale, such as look at stars in the night sky. Then in 2001, there’s a little guy population explosion, as Johns reworked a stack of rejected prints with collage, drawing, and painting, moving stick figures all over the place.

They seem to get fully incorporated into his repertoire and his process from then on, and used in a wide variety of ways. At the Walker, Wallace looks specifically at how the stick figures work in two later prints, from 2016 and 2020. They seem to mark scale and space wherever they go, often appearing, as Wallace notes, “as if actors on a shallow stage.”

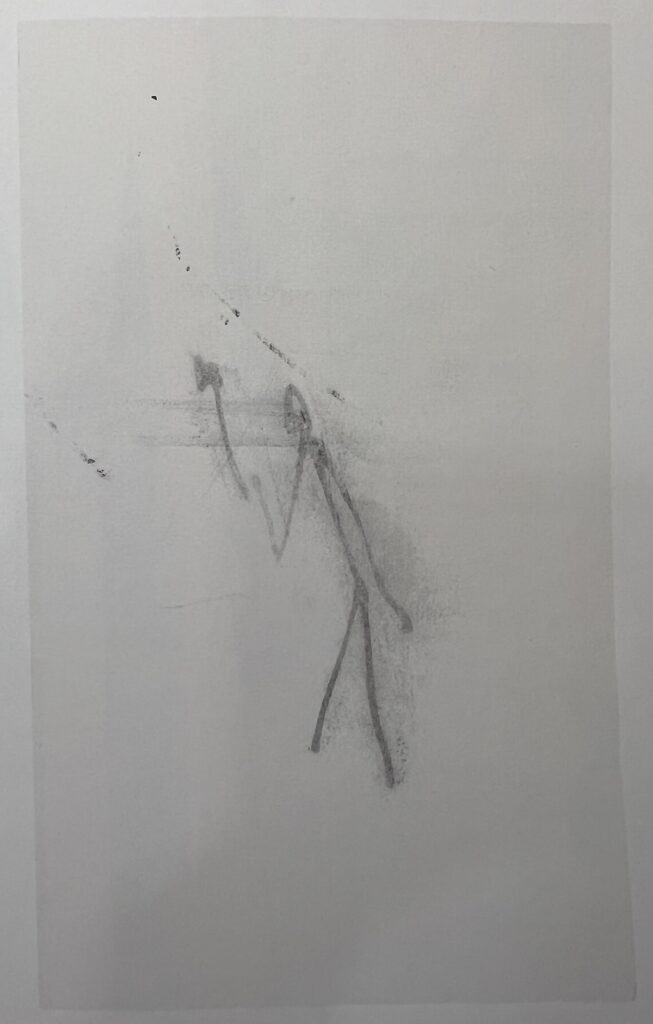

But I’m not sure they’re actors. In the beginning I thought these stick figures seemed like observers—stand-ins for the audience, not the artist. Which, admittedly, ignores the tools they carry. So are they artists? Or even the artist, and two friends? On this possibility, one work in the CR stands out, because for once, a stick figure stands alone—and it’s the one with the axe. It’s the back [front?] of a thank you note Johns sent to his dealer Matthew Marks in 2005. Whether the dealer or the artist is more likely to be wielding a hatchet, I cannot possibly say.

Previously, related: Jasper Johns’ Little Guys

Later, related: Jasper Johns: Take An Object. Add Some Little Guys To It