There are no more than two paintings by Albrecht Dürer in a public collection in the United Kingdom. One is this swirling, brushy depiction of an explosive, cosmic phenomenon on a small pearwood panel. The other, a meticulous devotional picture of St. Jerome in the wilderness, is on the other side of the same panel. The panel was only attributed to Dürer in 1957, and was acquired by the National Gallery in London in 1996.

Like all England’s museums, the National Gallery has been closed to visitors since December 2020, when a Tier 3 lockdown went into effect to reduce the transmission of the COVID-19 virus. According to current government indicators, museums will remain closed until at least May 17. So assuming it’s really by him, England’s only Dürers will remain inaccessible for at least several more weeks.

While considering whether an Albrecht Dürer Facsimile Object could offer even a partial experiential hedge during this challenging, Dürerless time, another, similar Dürer suddenly became similarly inaccessible.

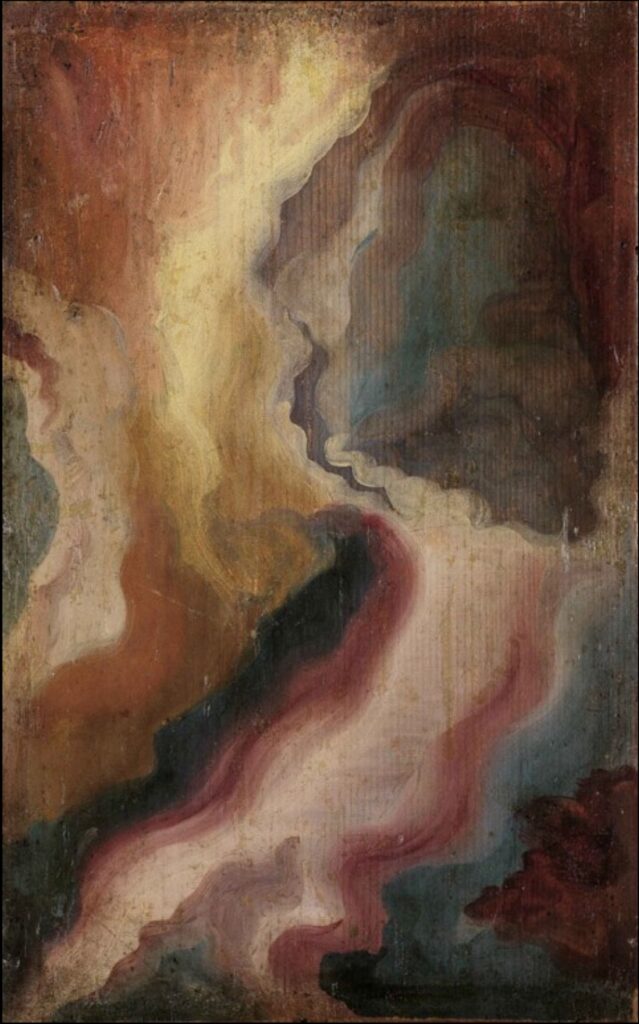

Another small oil, c. 1492, depicts a swirling abstraction of sliced agate or other hardstone, painted with a transparency that permits the grain of the fir panel to show through. On the other side of this panel is another small devotional painting, a gold ground picture of Christ, Man of Sorrows, which was attributed to Dürer a few years before 1941, when the Nazis’ favorite art dealer Hildebrand Gurlitt sold it to the Musée des Beaux Arts in occupied Strasbourg. It subsequently crossed the Rhine, and is now at the State Kunsthalle in Karlsruhe, which was closed on March 22 when German health officials abruptly declared lockdowns to thwart a “third wave” of the pandemic. The government then changed some restrictions after a backlash, but I think the Kunsthalle is closed until at least April 18.

“If a work is on Google Street View, does it even need a Facsimile Object?” is a question that came to mind. But then I wondered what would happen if these two works were decoupled from the paintings they are physically twinned with, the works they were fated to be “behind,” always understudied and overshadowed by? Facsimile Objects might hit different with this not-quite-a-pair. So let’s see.

Besides their verso curse, the relatively recent attributions of these paintings dealt both of these Dürers out of centuries of scholarly and critical attention. What little discourse exists seems unsure of what to make of these paintings, including whether they even relate at all to the paintings on their other sides.

In her note on the painting, Dr. Anna Moraht-Fromm describes it as either a lone panel or part of a broken diptych. Dr. Thomas Schauerte believes the back panel is just a decoration that “imitates a precious hardstone carving.” Moraht-Fromm argues for a metaphorical interpretation, seeing a cave that echoes the tomb where the suffering Christ would soon sojourn. Whether you disagree with her argument that the painting is a reference to divinus artifex, the divine artist of Nature, Beate Fricke is certainly right that it is “ein flammende Farbspektakel, [a flaming color spectacle].” I’ll take it. And if I can find a better image of the unframed panel than this–can you imagine being the guy who decides to paint your inventory number on top of a Dürer?–I’ll use it in place of my current, cropped option.

On the other painting, the heavenly object was titled ein Lichtblitz/Lightning Bolt, when it was shown at the Albertina last year. David Carlitt, the Dürer non-expert behind the original attribution, was baffled, wondering if maybe Dürer had painted his St. Jerome on a used panel. But he also did note the similar celestial object depicted in Dürer’s famous engraving of many years later, Melancolia I.

Whether it was “a meteorite, or shooting star,” or precisely what, “we shall never know,” Carlitt wrote, but surely, it “depicts an actual phenomenon observed by Dürer and jotted down while the impression of it was still fresh in his mind.”

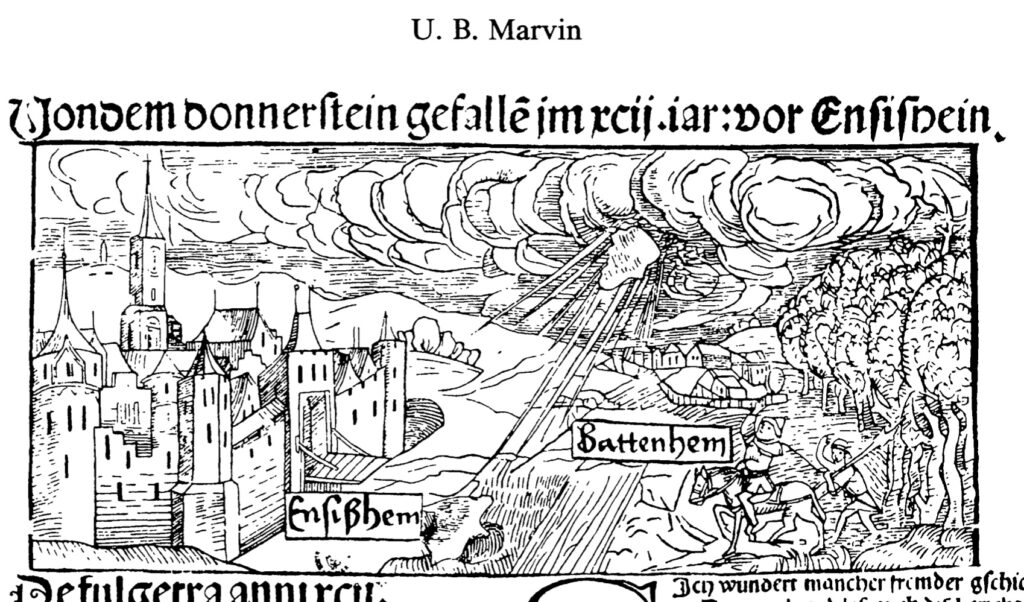

In 1992, Harvard’s Ursula B. Marvin wrote of similarities between Dürer’s painting and contemporary depictions of the Ensisheim Meteorite, the first witnessed and recovered meteorite in recorded (Western) history. On November 7, 1492, just after noon, a meteor was seen and heard across the Alsace region surrounding Basel. Crucially, there was a witness to the meteorite’s explosive landing in a field outside Ensisheim. The local magistrate ordered it to be preserved, not chopped up for souvenirs, and a couple of weeks later, the Emperor Maximilian, Dürer’s great patron, examined the 260-lb rock and declared it a sign from God–that he should proceed with his plan to attack France. Anyway, Marvin’s historiography of the meteorite is pretty thorough, surfacing various editions of the 1492 broadside announcing the meteorite’s portentous arrival [below]. It remains on view in Einsisheim to this day.

Dürer was working in the region at the time, including for a minute at the publisher of the broadsides. But the Ensisheim accounts say the meteor, or thunderstone, as they called it, arrived at mid-day, and Dürer’s painting seems to depict the dark of night. No other similarly dramatic meteorites were reported in a place or timeframe where our young artist could have seen it to whip out a sketch.

A 1986 article by Jean Michel Massing, though, offers an intriguing interpretation that explains the painting and its link to its flipside counterpart. The wet-in-wet brushwork, broad and visible, Massing writes, “clearly indicates this side of the panel was painted in a manner of minutes.” Pulling from Dürer’s own writings and the 15th century’s understanding of the dreams, imagination, and the mind, Massing traces Dürer’s interest in dreams, and in capturing them. “I often see great art and good things while asleep which do not occur to me awake. However, when I wake up the memory of them is lost.” From 1496 his work on his Apocalypse woodcuts was filling his waking life with portents of Doomsday, a St. Jerome-ian trademark. [“There fell a great star from heaven, burning as it were a lamp,” &c., &c., Rev. 8:10]. For Massing, “The rapidly recorded vision…suggests a dream in which, inspired by Revelations, the artist himself saw ‘great wonders, so that he maketh fire come down from heaven on earth in the sight of men.'” Who’s the recto now?

So these two paintings, vivid, rapidly executed depictions of something extraordinary the young Dürer saw, can now be seen together, in a way, as two Facsimile Objects. It would be wrong to call them a pair or a diptych.

R: Albrecht Dürer Facsimile Object (D2), agate, dye sublimation ink on aluminum, 30 x 18.4 cm

These two Dürer Facsimile Objects (D1) & (D2) are available separately or together, and only while COVID renders the originals inaccessible. Each is dye sublimation printed on aluminum and accompanied by a handmade certificate of authenticity. Unlike the Manet Facsimile Object, these will be prepared in small batches and ready to ship on a rolling basis, to increase the solace they can provide during lockdown, when it’s actually useful. I would like to not think about whether they will toggle in and out of availability as museums open and close again. And again.

[17 May Update: The National Gallery in London reopens, so (D1), a heavenly vision, is no longer available, either separately or as a diptych.

29 May Update: The Kunstalle Karlsruhe is reopening for visitors with negative COVID tests, or proof of vaccination or recovery. Today is the last day (D2) was available.

Thank you to everyone who has engaged with this project.]

[23 November 2021 Update: with COVID cases on the rise again, it seemed that the conditions for this project might reoccur. Both Dürers are not viewable in person right now. But the Kunsthalle is currently closed for reservations, and the National Gallery lists their Dürer as not on view, I think because it’s on loan? Anyway, seriously, people, please do not with the COVID again please.]