[October 11, 2022 update: the National Gallery returned this cock to Nigeria today, in a repatriation ceremony conducted along with the Smithsonian and RISD. The Art Newspaper reports that the decision to return this Benin bronze was approved by trustee vote in 2020. Excellent and quietly done, I guess this means nevermind!]

Benin bronzes have been in the news lately, and finally for a good reason: museums are finally starting to acknowledge their culpability in holding the thousands of Benin bronze sculptures and other royal artifacts that all made their way out of Africa the same way: via the British imperial troops’ so-called “punitive expedition” that destroyed the capital of the Kingdom of Benin, in present day Nigeria, in 1897.

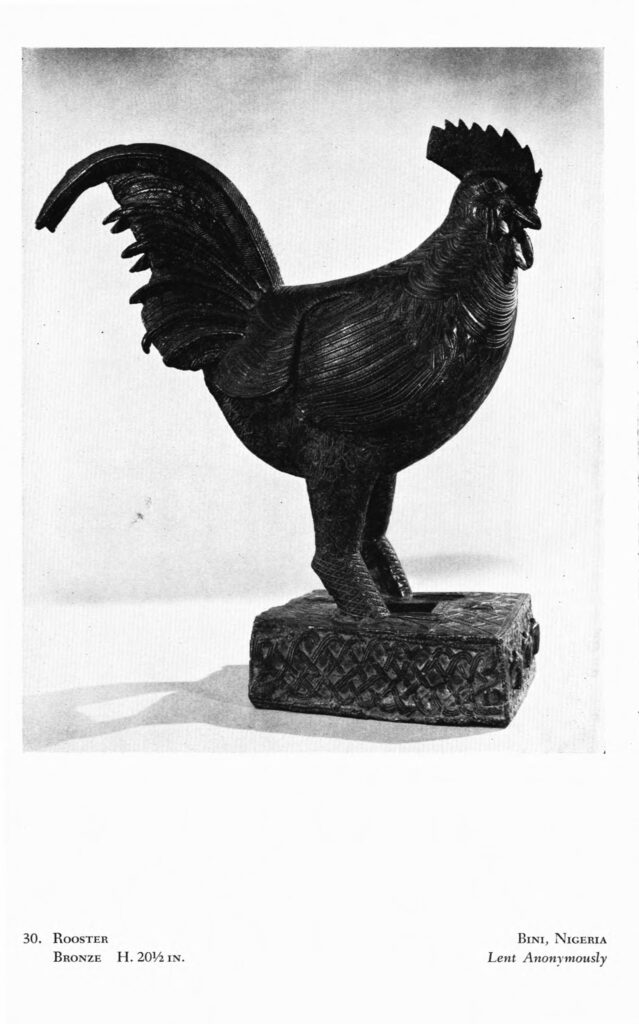

The British Museum and the Metropolitan each have hundreds of objects frankly labeled as the spoils of this massacre. Very unusually, and for absolutely no reason that I can find, the National Gallery of Art has exactly one: this c. 18th century Benin bronze rooster. Every couple of months for the last couple of years I’ve tried to uncover how this object got to the National Gallery, and why an African object would even be accepted, never mind kept, by a museum with no African art–and with almost no art beyond the European and American tradition. All I can figure is that this Benin bronze sculpture doesn’t belong at the National Gallery of Art, even if it weren’t stolen.

The rooster, officially called a fowl so they don’t have to say cock, I guess, is the only gift to the NGA ever made by Mr. & Mrs. Winston F. C. Guest, New York socialites who were well known for playing polo and being Winston Churchill’s cousin (Mr.) and for socializing (Mrs., better known as C.Z.) They donated the sculpture in late 1955, and it immediately went on the road; it was lent to an exhibition of African Art at the Allen Memorial Museum at Oberlin College, which opened in February 1956.

The Winter 1955-56 edition of the Museum Bulletin served as the exhibition catalogue, and contains a lecture given by William Fagg, deputy keeper in the Dept. of Ethnography of the British Museum, and reproductions of objects in the show. The rooster is the only object in the show to not list its owner.

I’ve been able to find zero connections between the Guests and anyone in senior leadership of the National Gallery at the time or before. The most likely facilitator of the donation is probably the dealer who sold the rooster to the Guests: J. J. Klejman. Klejman, who also went by John, had a prominent gallery on Madison Avenue, across from the Carlyle Hotel, that sold antiquities and non-Western art objects to America’s elites and to their museums. In 1963 JFK had Klejman assemble a selection of objects for Jackie to pick a gift from for their 10th wedding anniversary. And Klejman was a huge source of antiquities for the Met, including some whose transparently fake provenances later helped trigger the global treaties against looting. Klejman was the primary lender and chief facilitator of the Oberlin show. But I can find no evidence of why or how Klejman might have orchestrated the donation of piece to the NGA, or why the NGA would have accepted it. It all seems so random.

About the only documentation the NGA’s files contain on the rooster is a letter from Klejman to Guest on 30 November 1955, its presumed purchase date, affirming that the sculpture was taken in the 1897 punitive expedition. The Benin rooster’s association with colonial violence and cultural genocide was also its certificate of authenticity.

The overlapping timing of the purchase, authentication, donation, accession, and exhibition feels extremely odd. The National Gallery’s lack of named involvement in the Oberlin show feels odd. While it has been loaned to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art (and its predecessor institution) multiple times over 65 years, it’s not clear if it’s been exhibited at the National Gallery itself, ever.

[The Smithsonian, in addition to a trove of Benin bronzes and other artifacts it received from Joseph Hirshhorn’s massive gift in 1966, also got its own Benin rooster in 2005, when it accepted the 525-piece collection of African Art the Walt Disney Corporation bought from the Tishman family, who built EPCOT, for an unrealized museum project at Walt Disney World.]

There is probably not a Benin bronze object in any museum anywhere that has less institutional reason to keep it than the rooster at the National Gallery. Maybe at another moment in history, someone could have made an argument that it should be transferred to the Smithsonian. Now, though, I think it’s clear that the National Gallery needs to help the Smithsonian make a tough decision by making an easy one: and announce they’re giving their Benin bronze rooster back.