In her tweet about Geoff Edger’s Washington Post story of how a high school athlete from Cameroon’s drawing of a knee ended up in a new Jasper Johns painting, the Times’ editor said the story had originally been reported by Deborah Solomon two weeks ago. Which it both had, and very much had not.

And what who knew when and what happened when and who was involved is central to the issue at hand, which is ultimately that Jasper Johns draws on images from the world around him to make his art, and what does that mean? Another issue at hand: who are all these people, and does anyone in Litchfield County have anything to do besides be all up in Jasper Johns’ business?

Johns first saw Jéan-Marc Togodgue’s drawing of a knee on the wall of his orthopedist, Alexander Clark, in 2019. Clark explained it was by a young man from Cameroon. Johns presumably liked it enough to take a picture of it. Is that what’s it’s like in Sharon? Is Johns just whipping out his phone around town, to take a pic of his latte art, or the charcoal display at the hardware store, or the new screens on the gas pump? If so, none of those images have yet to find their way into his work.

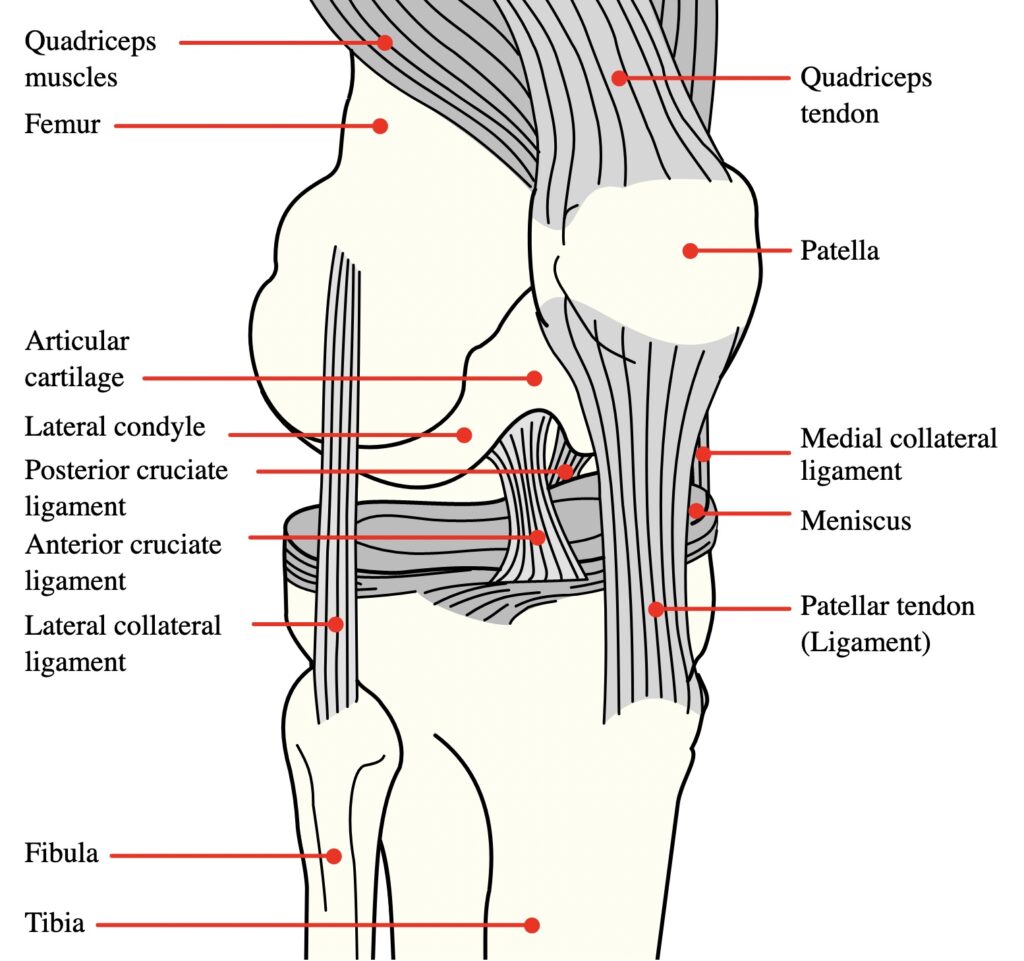

Edger said Togodgue made his drawing in 2017–he would have been 13 or 14–after tearing his ACL; he based it on “an image he found on the internet.” That image, of course, is from the Wikipedia page for “anterior cruciate ligament.” The labels on Togodgue’s drawing don’t match the French file on Wikipedia, but do match the results of Google Translate. It is unlikely that any of this is of interest to Johns, or influenced his decision to use the drawing as an element in his work.

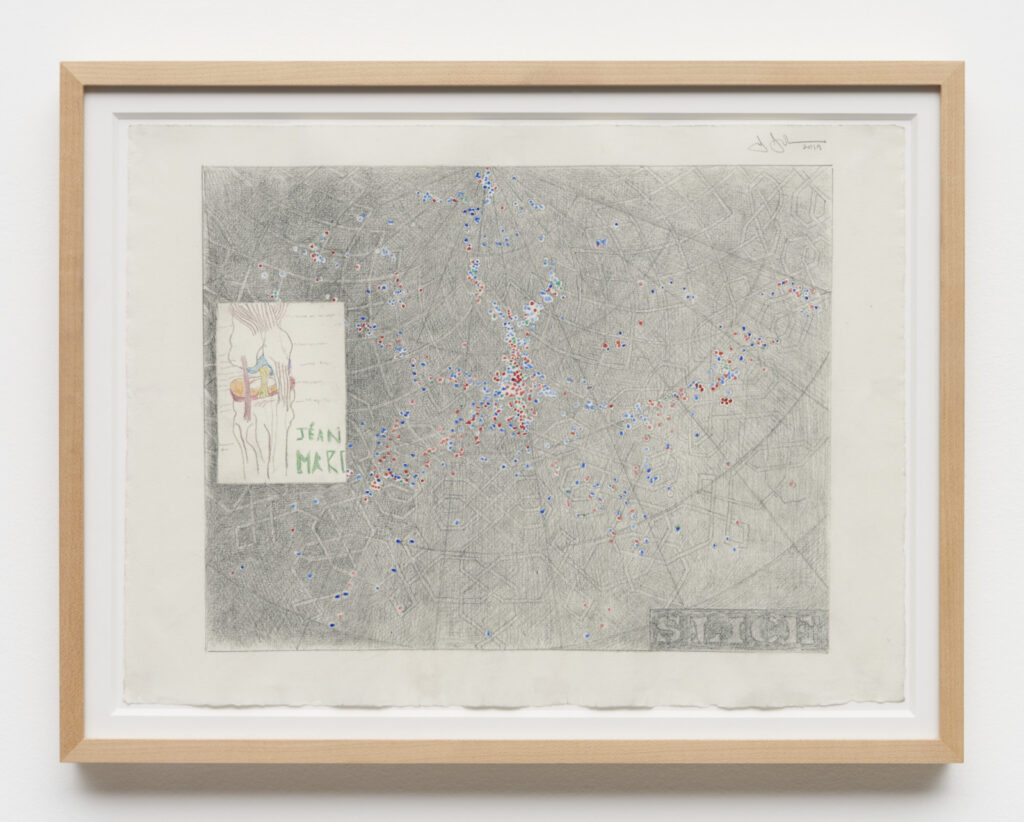

Edger said Johns had begun working on this painting, “Slice,” in 2019, which may be true. It is dominated by a 1986 astronomical map titled, “Slice of the Universe,”showing the threadlike distribution of galaxies in space, which the artist received, unsolicited, from astrophysicist Margaret Geller in 2018. Solomon said Geller received a letter from Johns “Early in 2020” to let her know he was considering beginning a painting for which she would be partly responsible.

But. The oldest work in the show of new works on paper at Matthew Marks is dated 2019. It is one of 13 works to include Geller’s map. Five of those 13 which also include Togodgue’s drawing. Four drawings–the other three are from 2020–show various compositions for the map and the drawing (and details of Leonardo’s knots, another, more diffuse element of the works.) Another group of six overpainted and collaged etchings include a muted, transformed version of Togodgue’s drawing replaced with five alternate images ranging from antique Japanese porn to another copy of Geller’s map itself. All dated 2021, they use the map of the universe as a platform for incorporating other images; they also look like explorations of what Slice might look like without Togodgue’s drawing.

It is entirely possible to read Edger’s piece, even plausible, to conclude that Johns had no expectation of any need to contact Togodgue for permission to use his drawing as a silkscreened element in a painting. It’s also logical to assume that he did contact him only after the painting was complete, and perhaps when it was being photographed, and being discussed as the flagship image for the Whitney & Philadelphia Museum’s joint exhibitions.

It is also possible to conclude that until Johns successfully completed the painting, he not only didn’t know Togodgue’s identity–his finance/bespoke innkeeper/local go-between Conley Rollins says as much–he didn’t even know Togodgue was not actually in Cameroon, but attending boarding school just minutes away on a basketball scholarship [Salisbury, not Hotchkiss.]

It is possible, but though it is, I confess, less plausible, to conclude, as Rollins would have us believe, that he was to blame for not telling Togodgue and his growing entourage of coach/host/incredulous interventionists sooner that Johns had wanted to give the young man a drawing. How unfortunate that in that delay, an indignant artist whose kid went to school with Togodgue accused Johns in writing of intellectual property theft and racist insensitivity, and demanded he create a foundation for Cameroonian athletes. All very awkward, anyway, a deal was reached that seems not to involve a drawing.

All the events in Edger’s story went down before Solomon’s first view of Slice in July. The entire framing of her article, the public reveal of the painting, focuses on Geller, her letter, and her map. Togodgue is described simply as “a high-school student from Cameroon.” It seems highly unlikely that Solomon would omit news about the knee drawing if she knew of it. So the story had to have come out after the Times drop, probably from one of the seemingly endless chain of people Togodgue’s posse told his story to, all the people who thought the kid should get mad bag from Johns. And who now tell him to hold onto his original drawings, because–because what? Do they want him to open up an etsy store now? Johns and the museums hired the head of crisis management at Rubinstein to deal with this?

At the end of it all, I’m struck by the number of people forming protective entourages around both these artists, and how differently these posse members go about their business. Slice is currently on view at the Whitney.

First Look: Jasper Johns’ “Slice” [nyt]

“Slice,” a work on view in new Jasper Johns’ show at the Whitney, raises complex questions [wapo]