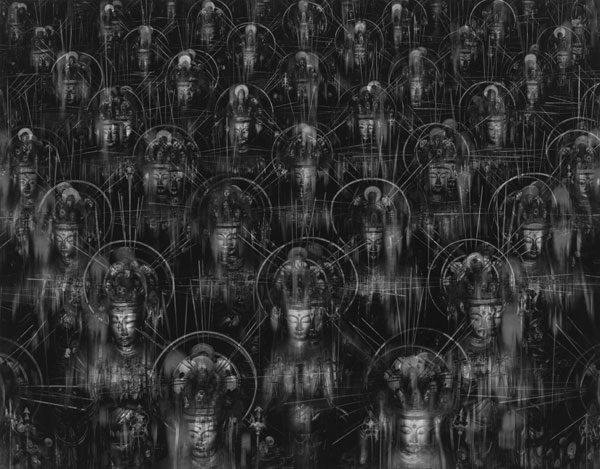

Hall of Thirty-Three Bays, 1995, Hiroshi Sugimoto

Hiroshi Sugimoto: I came for the Seascapes, I stayed for the Hall of Thirty-Three Bays. I love Sea of Buddhas, 1995, his series of nearly identical photos of the Sanjusangendo, shrine in Kyoto. They’re generally under-appreciated, partly because they work best when seen all together.

Fortunately, Chicago has started making up for the Cow Parade embarrassment by putting the whole series of Sea of Buddha on view at the Smart Gallery at the University of Chicago until Jan. 4th.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Still image from Accelerated Buddha, added 2013

Also on view, the artist’s rarely seen video, Accelerated Buddha, which rocks like only an increasingly shimmering animation of nearly identical still photos with a sharp electronic soundtrack by Ken Ikeda can.

Related: an interview with Hiroshi Sugimoto [update, which I retrieved from the Internet Archive, since the original site is gone.]

Interview with Hiroshi Sugimoto, March 1997

by William Jeffett

Edited from Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK Catalogue Hiroshi Sugimoto, from an exhibition held 1997

WJ. How and when did you first take up working with photography?

HS. When I was six or seven years old, the science teacher at my elementary school taught us to make photographs with light sensitive blue paper. By placing an object on this paper under direct light we could transfer its shape to the paper’s surface. This activity made a strong impression, not only on the paper, but on my mind. As I think about it now, it was as if I had started at the very moment of the invention of photography as if I was reliving the experiences of photographers like Niepce, Daguerre and Fox Talbot.

WJ. You have lived in the United States for most of your career. How has this shaped the development of your approach to photography?

HS. Wherever I lived, art was the only activity that interested me. But both the move to a new country and the fact that photography is a relatively young medium seemed to welcome new attitudes. However, while living in a new country, I started to deal in ancient Japanese art and consequently was involved with continuity and tradition. I think my work is the product of both of these influences.

WJ. What does it mean for you to have a show in the Sainsbury Centre with its rich collections of world art?

HS. The Sainsbury Centre has a collection of several works of ancient Japanese art that were acquired from me while I was still a dealer, and I feel that this exhibition of my own work brings these two parts of my life and activities together. I think it is very good to see one’s work together with ancient art. Looking back gives a sense of perspective you cannot get when looking at works of your contemporaries.

WJ. Often there is a sense of stillness in your work, as if time were somehow frozen. Indeed, time is one of the features more evident in your work, and in the past you have even used very long exposures in a time lapse. Could you tell me about your thoughts on time in your work in general?

HS. Time is one of the most abstract concepts human beings have created. No other animals have a sense of time, only humans have a sense of time. But time is not absolute; the time measured by watches is one kind of time, but it is not the only kind. The awareness of time can be found in ancient human consciousness, arising from the memory of death. Early humans buried their loved ones and left marks at the grave site, trying to remember images of the dead. Now, photography also remembers the past. I am tracing this beginning of time, when humans began to name things and remember. In my Seascape series, you may see this concept.

WJ. Your work has taken both natural and highly artificial subjects as a point of departure (Seascapes and Dioramas). Where would you situate yourself in relation to artifice, on the one hand, and nature on the other?

HS. The natural history dioramas attracted me both because of their artificiality and because they seemed so real. These displays attempt to show what nature is like, but in fact they are almost totally man-made. On the other hand, when I look at nature I see the artificiality behind it. Even though the seascape is the least changed part of nature, population and the resulting pollution have made nature into something artificial.

WJ. Do you manipulate the image? In what way does your work interrogate the process of looking?

HS. Before we start talking about manipulation, we have to confirm the way we see. Is there any solid, original image of the world to manipulate from? Each individual has manipulated vision. Fish see things the way fish see, insects see things the way insects see. The way man sees things has already been manipulated. We see things the way we want to see. Of course I manipulate. Artists create excitement by manipulating a boring world. All art is manipulation, to take still photography with black and white images is further manipulation, but before all this the very first manipulation is seeing.

WJ. You work in series and in this respect your work parallels the approach of movements like Minimalism or even Pop Art. Could you tell me why you have adopted a serial approach and how you see your photography in relation to other forms of contemporary art?

HS. I see the serial approach in my work as part of a tradition, both oriental and occidental – Hokusai’s views as well as Cézanne’s landscapes or Monet’s Haystacks, Cathedrals and Waterlilies.

WJ. Do you see time as an important component in the Hall of Thirty-Three Bays series?

HS. Time is an important component of all of my work. In my videotape Accelerated Buddha, time takes on an accelerated shape.

WJ. Your earlier series devoted to the Dioramas, Seascapes and Theatres depict subjects which are not recognizably Japanese, while the Hall of Thirty-Three Bays is based on one of the most important shrines in Japan. Could you tell me why you chose this series to work on over the last six years and how it relates to your other work?

HS. All of my works are related conceptually. The photographs of the Hall of Thirty-Three Bays extend the concept behind the Seascape series: repetition with subtle differences. Even though these images seem similar to those of the Wax Figures, I see them more as a ‘Sea of Buddhas’.

WJ. In what way does the series have a connection with Buddhist thought?

HS. I don’t think that this series has more of a connection with Buddhist thought than any of my others. It interested me, however, that I was photographing this temple, built as a result of the fear of a millennium 2000 years after the birth of Buddha, at a time when we ourselves are approaching a millennium 2000 years after the death of Christ.

WJ. You said you made each of the photographs from this series at the same hour of the morning. Could you say why and explain a little about your working method?

HS. The photographs were all taken between 6.00 and 7.30am so that the natural light would be soft and diffused, also so that each image would be photographed in the same light. Working at this hour also allowed me to be alone in the Temple since the monks are not around until 7.30am. Each subject calls for different working hours. Only the Seascapes allow me to work 24 hours non-stop.

WJ. The Hall of Thirty-Three Bays depicts a sacred subject. Do you see your work as in any way engaged with the sacred?

HS. The relationship between the Buddha series and religious thought is somehow parallel to the one between the Seascapes and nature. Pollution has made nature artificial and the commercialization of traditional religions has de-spiritualized them.