In 1969, Allen Ruppersberg created Al’s Cafe, a detailed, functioning facsimile of an archetypal diner, which was to operate/perform one night a week. Allan McCollum, who was making work in Los Angeles at the time, wrote about Ruppersberg and Al’s Cafe in a 2001 catalogue essay:

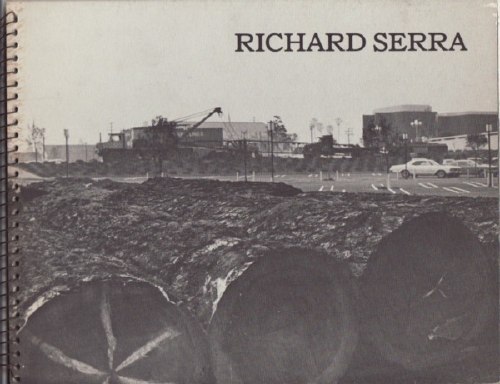

I would like to explain a little of why this piece was so significant in L.A. in 1969. “Site” works and “performance” pieces were proliferating at the time; in 1970, for instance, Richard Serra would create an outdoors-brought-indoors installation at the Pasadena Art Museum, in which three immense California redwood logs were leant upon a fourth, and their cantilevered ends were sawn off and allowed to crash to the floor. The aftermath of this action created an enormously dramatic display, and the project was much talked about. Elsewhere, a number of artists of these years were crowding into their cars and heading out to the deserts to work with natural processes, the results of which were often brought back from such alternative, poststudio locales to wind up in the same clean white gallery spaces that the artists seemed to have abandoned so pointedly. Robert Smithson had worked to point out the dialectical relations between the “nonsites” of the urban galleries and the peripheral “sites” of marginalized geographic territories: slag heaps, rock piles, dry lakes, landfills. He and others who followed took to the Midwestern plains and the Western deserts, executing projects in the middle of nowhere, and bringing back aerial photographs, sketches, documentation, and truckloads of residues and samples from these relatively exotic, empty regions of the American map to display in the populated cities. A new vocabulary was building, and an exploration of how our culture’s richness and complexity have always been framed and defined by our fantasies of the sophistication of our urban centers, and the purity of their showplaces and shrines, in relation to nature’s marginalized and boundless emptiness.

A dilemma was beautifully revealed by these pioneering artists–and clearly spelled out for the younger artists–and the question (“naturally”) arose: isn’t our idea of nature just another idea? Another concept? Another cultural artifact? Does moving out of our urban habitats to make art really accomplish anything beyond promoting a further alienation, a further fiction, another kind of imperialism, a new imaginary idea of purity? It was within this growing discourse that Al’s Cafe offered to sell a “JOHN MUIR SALAD (BOTANY SPECIAL),” or “GRASS PATCH WITH FIVE ROCK VARIETIES SERVED WITH SEED PACKETS ON THE SIDE.” In Al’s Cafe, Ruppersberg answered the growing mannerisms of Earth art with a slyly symbolic display of nature as always mediated, always already determined by the culture that processes it–both literally and figuratively–for its own use. He presented nature as a commodity for consumption, without the pretense of any pure “natural” vision.

I really planned to just quote the Serra description [emphasis added]. I’d heard references to the work before, but never to the process and content of the piece. Which means, I guess, I’ve never seen the catalogue for Serra’s one-man Pasadena show, which documented the making of the work, which was titled: Sawing: Base Plate Template (Twelve Fir Trees). Also, I don’t think they were redwoods.

Smithson himself had installed a Non-site, Dead Tree, which consisted of just one tree, in the Dusseldorf Kunsthalle in 1969. Joe Amrhein and Brian Conley’s 2000 re-creation of Dead Tree in Pierogi 2000 was a classic. [Here’s a Frieze review by David Greene.] What’s been written–or exhibited–about these two guys’ early history together?